There’s big money to be made in our jails and prisons. Just ask Securus Technologies, Inc.

In 2013, the Multnomah County Sheriff’s Office (MCSO) signed a four-year contract with the Texas-based prison-industry giant, allowing it and two other out-of-state corporations to begin profiting off Multnomah County inmates and their families — charging for services the county historically provided free of charge.

Under the terms of the contract, one of the three corporations is profiting every time a deposit is made onto a Multnomah County inmate’s account, another profits from fees charged to inmates who are issued a debit card upon their release, and the third profits from its video visiting system. The contract requires the county to eventually eliminate in-person visiting and promote video visiting instead.

With the exception of attorney and other professional visits, all in-person visiting will be eliminated in Multnomah County correctional facilities by the end of this year, according to a MCSO spokesperson Lt. Steven Alexander. That’s if the planned installation of the video visiting systems is completed on time. After the switch is made, family and friends of MCSO inmates will only be able to visit their locked-up loved ones by communicating through a box with an attached phone for audio and a small video screen for visual. Prior to the video setup, visits in MCSO jails were done with the inmate and visitor only a few feet from each other, on a phone, with a piece of shatterproof glass between them.

Unless you’re using the visitation kiosks in the jail, charges will apply.

Securus is only one of many companies profiting by charging families of prisoners money for services now outsourced from the correctional system. Today, Securus serves 2,600 facilities in 46 states. It boasts that it has paid $1.3 billion in commissions to correctional facilities over the past 10 years. In 2009, the last year financial information was made publicly available, Securus brought in more than $363 million in revenue.

Video “visits”

Video visiting has “really taken off over the past three years,” says Prison Policy Initiative spokesperson Bernadette Rabuy. Her organization has been studying the prevalence and effects of video visiting across the country, and she says it’s more common than she previously thought, with upwards of 500 facilities using the service. Visits can be conducted on site, usually from the lobby of a correctional facility, or remotely, which can benefit inmates whose families live far away, which is often the case with state facilities. But, says Rabuy, “In the county jail context, it’s been really harmful.”

According to the Dallas Morning News, Dallas County, Texas, turned down a similar deal with Securus last year on the grounds that the “elimination of in-person visits was inhumane.”

Rabuy says Securus is the only company offering video visiting that requires the elimination of in-person visits in all of its contracts. While the technology for video visiting has existed since the 1990s, Rabuy says most systems, including Securus’s, still experience many glitches, with frozen screens, audio delays and poor picture quality. In testing, Rabuy says she experienced 10-second audio delays that made communication during the video visit virtually impossible.

Rabuy says her organization has found it’s difficult for family members to determine the well being of an inmate through the small screen, something that’s very important to them. They can’t tell if the inmate has lost or gained weight or see changes in their skin tone. Prison Policy Initiative’s study on video visiting will be released later this month.

Street Roots asked Multnomah County Sheriff Dan Staton if he thought the switch to video visiting at MCSO facilities would make visiting less personal than it was with face-to-face visits. In an e-mail response, his office didn’t answer the question, but stated, “We are not the first ones to implement video visiting in Oregon or the nation. Frankly, we are behind the curve on this one and are the last large jail in Oregon to move to video visiting. Before, a person wishing to visit an inmate in MCSO custody had to travel down to the jail facility the inmate was housed at on a Saturday or Sunday, the scheduled visiting days for each facility.”

The new system has its advantages, says Alexander, pointing out that now people can visit inmates, remotely, any day of the week and on holidays. Last month, for the very first time, inmates were able to receive “visits” on Christmas Day. He says in-person visitation will most likely be entirely eliminated by the end of January at Multnomah County Inverness Jail, and by the end of the year at Multnomah County Detention Center in downtown Portland.

Becky Straus, legislative director with the the ACLU in Oregon, says on just face value, they don’t have problems with the video visitation.

“Anything that can make it easier for inmates to be in touch with loved ones is a good thing,” Straus said. “Burdensome fees on accessing video chat, however, make visitation harder rather than easier, putting an additional fiscal burden on inmates and their families. In no circumstances should video chat be the only option for visitation. Eliminating in-person visits altogether is likely to make inmates feel more isolated and could lead to a greater chance of recidivism.”

Between last May, when video visiting was introduced, and mid December, 211 out of a total of 2,169 video visits were conducted remotely for $5 each. The rest were conducted on-site and free of charge at a MCSO facility.

The county receives a 20 percent commission from each remote, paid video visit, but right now the commissions are going toward paying off the $600,559 installation of Securus’s systems. If remote, paid visits don’t reach an average total of 1,265 per month, a number based on the county’s average daily population, then Securus has the expressed right to renegotiate payments. It also has the right to raise the $5 “promotional” cost of a remote visit up to as much as $20 per 20-minute session, but county spokesperson Alexander says he doubts it will ever raise rates that high. On-site video visits conducted at MCSO facilities will always be free, he says.

Fees for services

Under the contract with Securus Technologies, MCSO also implemented a debit card system run by Numi Financial. Since the debit card’s implementation last spring, the jail no longer returns personal cash to people released from jail. Instead, a person would receive a debit card loaded with the money when they are released. They have five days to get their money off the card before it begins to incur a monthly maintenance fee of $5.95. Fees also apply to non-preferred ATM withdrawals, balance inquiries and paper statements. The cards are given to everyone who was carrying cash when they were arrested, regardless of their length of stay at a MCSO facility.

Also based in Texas, TouchPay GenPar, LLC. was subcontracted through Securus to operate new kiosks in Multnomah County Correctional facility lobbies, enabling TouchPay to collect a fee every time someone puts money into an inmate’s account. Alexander says the county plans to also use this system for posting bail.

The fees range from $4 to $8, depending on the amount and method of the deposit. If paying with a credit or debit card, 3.5 percent of the face value of the deposit is also tacked on to the total cost. Street Roots asked Multnomah County how much TouchPay has collected from deposits made to accounts within its corrections system, but the county does not keep record of that data, and TouchPay didn’t respond to our inquiry by press time.

According to advocacy groups, excessive fees charged by for-profit prison-industry companies put an additional financial burden on inmates and their families, many of whom are living in poverty.

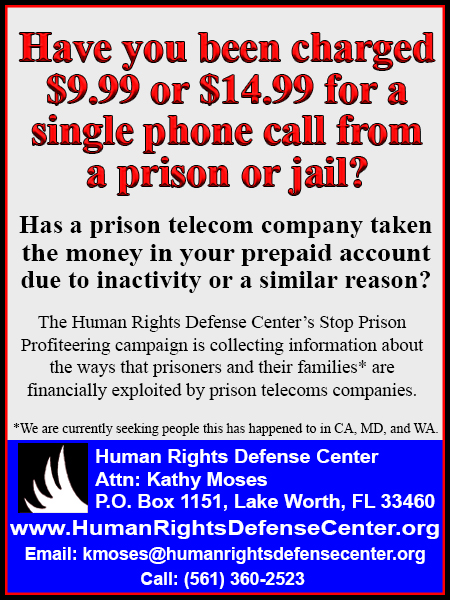

“These companies, like Securus, have figured out a way to monetize both human contact and the only way a prisoner’s family can help them out,” says Carrie Wilkinson, Phone Justice Director at Human Rights Defense Center. Her organization has been pushing for legislation that would regulate the fees charged by the prison communications industry.

Financial burdens

Portland resident Leslie McCarthy has a son serving time at Two Rivers Correctional Institution in Umatilla, Ore. The fee charged by Access Corrections, the company contracted to handle inmate accounts at Two Rivers, jumps from $2.95 to $5.95 if she deposits $20 or more. For this reason she deposits $19.99 on his books each month so she can avoid the higher fee. She says she feels as though putting money on his account is a necessity. “You do way better in prison if you have money,” she says. Without money, her son wouldn’t be able to brush his teeth with toothpaste or wash his hair with shampoo, she says.

Multnomah County’s decision to have a corporation take over the management of inmate monetary funds came after a 2011 county audit found the way the department handled cash was needlessly cumbersome, with staffers recounting the same bundles of cash multiple times. In light of the audit’s recommendations, the county decided to do what many other correctional facilities across the country and the state have already been doing for some time – hand the responsibility over to an outside, for-profit agency. The move was projected to save the sheriff’s office, with a budget of $122.3 million in the last fiscal year, about $23,000 annually.

Before the TouchPay kiosks were installed, visitors could put money on MCSO inmates’ accounts without paying a fee. The county does not receive any portion of the profits garnered by TouchPay from account deposits.

Street Roots asked Sheriff Staton how he would respond to someone who might say it’s unfair to pass these costs onto inmates’ friends and family, many of whom are experiencing poverty. In a written response, his office instead talked options: “The Sheriff’s Office has historically absorbed all of the costs associated with handling cash deposits and processing those deposits…When we moved to this new system it provided better security controls and accounting to comply with the County Auditor’s recommendations, but we also looked to provide a solution that allowed more flexibility for someone to make a deposit on an inmate’s account. With this new solution, there are now several ways to make a deposit to an inmate’s account without even having to travel down to one of the jails. A family member or loved one can make a deposit over the Internet, or even call a 1-800-number to make a deposit over the phone.”

These increased options, says the Sheriff’s office, save time and cost of travelling down to a jail. But all of them also cost the family member or loved one between $4 and $8 per transaction. Other transactions, such as money orders and cashiers checks, are no longer accepted at the county per Securus’ request in the contract.

“As a mom, you want to do everything you can to stay in contact with your child,” says Tamra Craig, who works in Portland as a caregiver. Her son is currently serving time at the federal correctional facility in Sheridan, Ore. She often puts money on her son’s prison account so he can buy phone and e-mail minutes and commissary items. She says she can barely afford the price of his incarceration. “The financial burden is more than I can express,” she says. “Sometimes I forgo things at the grocery store.”

According to Wilkinson at the Human Rights Defense Center, hiring companies like Securus is not how a government agency would traditionally fund its operations. “If the school district is running short of money, the school district doesn’t go to the parents of all the kids and say, ‘You have to pay $50 each because we’re running short of money,’” she says. “And in effect, that’s what’s happening. The only people that are providing this money are the prisoners’ families, and in most cases they’re poor and least able to provide this money.”

Jimmie Stewart, whose son Jason Angelo is in Mill Creek Correctional Facility in Salem, says the financial burden of her son’s incarceration is “very difficult.” Her son’s wife, a student, and his two young boys are living with Stewart and her husband in a two-bedroom apartment in Portland while her son serves his time.

Stewart and her family absorb costs associated with putting money on her son’s books. Mill Creek employs JPay for account deposits, which, like TouchPay, charges a sliding scale of fees for its services. It costs $3.95 to send a deposit of $20 or less. This may not seem like a lot, but for someone with little means, it’s a hefty fee. Angelo’s wife has resorted to giving blood in order to put money on her husband’s account.

Stewart says she’s been trying to sort out a mistake made by JPay in November. She says she tried to send $100 to her son, and while JPay accepted the payment, the prison says it never received it. She says JPay has acknowledged the mistake, but by press time, JPay had neither returned her money nor forwarded it to Mill Creek.

National studies show the majority of prisoners have at least one child under the age of 18. For some families, keeping the line of communication open between parent and child is important, even when doing so isn’t affordable.

Stewart pays what her son’s wife can’t toward phone charges in order to make sure her son doesn’t lose contact with his sons.

“These are important times,” she says. “His oldest son is in preschool, so he tells daddy everything he’s done in school that day, and the 2-year-old is just starting to talk, so now he can tell daddy his new words,” she says.

They’ve done video visiting a few times, but at $9 per visit, she says it’s too expensive.

Stewart’s son works four days a week on a work crew at the prison, which pays him about $40 a month, says Stewart – less than half of what she pays in phone charges most months.

Costly contact

Before the Multnomah County Sheriff signed the deal with Securus Technologies, the prison communications leader had already been pulling in millions of dollars from Multnomah County inmates and their families for years with high fees on collect calls. Under the 2013 contract with the county, Securus, along with its subcontractors, has expanded its revenue potential with the addition of inmate financial transactions and visitations. Local departments benefit with commissions.

In Multnomah County, Securus charges $5.43 for a 15-minute local call. The commissions made by the county from phone calls go into the Inmate Welfare Fund, which was set up to pay for activities and services that benefit inmates. But over the past two fiscal years, $92,521 was taken out of the Inmate Welfare Fund to pay for other things on the county’s agenda, such as an Eastside Streetcar assessment. The Inmate Welfare Fund was one of only a handful of funds diverted as part of a supplemental budget both years.

The phone charges on inmate families caught the attention of Federal Communications Commission.

Last year the Human Rights Defense Center and other advocacy groups that were pushing for prison phone industry regulation celebrated a victory when the FCC capped costs on interstate calls made from correctional facilities. Now, impending regulations from the FCC might also cap rates for local collect calls as well, which account for 85 percent of all calls made from county jails. The public comment period for the upcoming FCC decision ends Jan. 5, and a decision is expected by mid year.

After looking at data from 14 U.S. correctional facilities, the FCC estimates that in 2013, more than $460 million was paid to correctional facilities in commissions off of phone charges alone. “This means that (inmates) and their families, friends and lawyers spent over $460 million to pay for programs ranging from inmate welfare to roads to correctional facilities’ staff salaries to the state or county’s general budget,” the FCC stated in a notice of the proposed cap.

According to MSCO’s 2015 adopted budget, it’s been collecting about $400,000 a year from Securus in phone commissions over the past two years, but according to a MSCO spokesperson, that phone revenue has decreased since the FCC put caps on interstate collect calls.

The bulk of Securus’s revenue comes from phone charges. If the FCC decides to cap fees for local calls as well, Securus and other prison communications companies might have to rely more heavily on other products and services for making money from their captive consumers.

Some consumers — at least those footing the bills — have fired back.

The Better Business Bureau lowered Securus’s rating due to the number of complaints filed against it – 443 in the past three years. According to the BBB’s Dallas and Northeast Texas website, where Securus is based, most complaints allege Securus “fails to provide acceptable product quality for its prison call services,” and that it “fails to provide refunds in a timely manner.” Last September the BBB contacted Securus, requesting that it eliminate the underlying reason for a pattern of consumer complaints, but it has yet to receive a written response to its request for voluntary compliance.

Securus boasted record growth in 2013, and in a press release its president and CEO Richard Smith stated, “Our expanded product set of inmate phone calling, on-site and remote video visitation, data analytics, parolee GPS monitoring, jail management (IT Systems), location based wireless tracking services, interactive voice recognition systems – and 650 other products will allow us to grow and serve our customers well into the foreseeable future.”

Mothers of Incarcerated Sons Society

The three mothers of inmates Street Roots spoke with for this story are members of the national nonprofit Mothers of Incarcerated Sons Society Inc. Rhonda Robinson founded the group out of her Michigan home in 1992 after her own son went to prison. It has since grown to be an online support group with 1,800 members nationwide and 31 members in Oregon. MISS is open to anyone who has a loved one serving time in a correctional institution.

“Members are constantly posting discussions regarding their financial burdens with high phone rates,” says Robinson. Her website hosts online discussions on different topics and serves as a source of support to people dealing with the pain of having an incarcerated family member. Many Members of the group are also actively advocating for changes to the prison system, tackling issues like mandatory minimum sentencing laws, solitary confinement and air conditioning in prisons.

In 2013 MISS held its first national conference in San Diego, and it plans to hold its second this year in Michigan.

To learn more, visit: mothersofinmates.org