PLN managing editor comments on post-release housing for ex-prisoners

In Nashville's tight rental market, people with conviction histories struggle to find a home

McArthur Sledge has put a tall plant in his living room, near a green easy chair where he sits to watch the evening news and the Titans. He sets out candies for visitors.

After serving 20 years in prison, he has lived in the Antioch duplex for the past year and pays rent each month to Project Return, a local nonprofit that connects formerly incarcerated individuals to employment.

"It is like night and day, the serenity, peacefulness," Sledge said. "It’s a breath of fresh air for me."

Project Return officials found that, even among those securing steady jobs, many people still struggle to find housing after incarceration. Landlords are often reluctant to rent to formerly incarcerated individuals, prompting Project Return to enter the rental business. In the past 18 months, the organization has bought 16 homes in Antioch, Madison, South Nashville and North Nashville to rent out as part of its PRO Housing initiative.

The nonprofit's goal is to acquire 50 homes in the next five years. Rather than develop several attached apartment buildings, Project Return is intentionally buying properties spread throughout the city in what Executive Director Bettie Kirkland describes as a "scattered-site model."

"(It is) basically replicating the private rental market, but making those homes available to hard-working people who happen to have a conviction history," Kirkland said.

In Tennessee, more than 10,000 individuals were released from Tennessee prisons in 2017. For housing, those leaving often turn to family members, halfway houses, homeless shelters or hotels, which can quickly absorb any earnings. Some become homeless, Kirkland said.

The cost of housing is part of the challenge. Nashville has a competitive rental market, with the average one-bedroom rent at $1,197 in April, according to RentJungle. That is up 70 percent from the same month in 2013.

“It was an uphill battle, primarily because of not having enough money,” Sledge, 56, said. "When you try to secure a residence, they want you to make three times more than what the rent is."

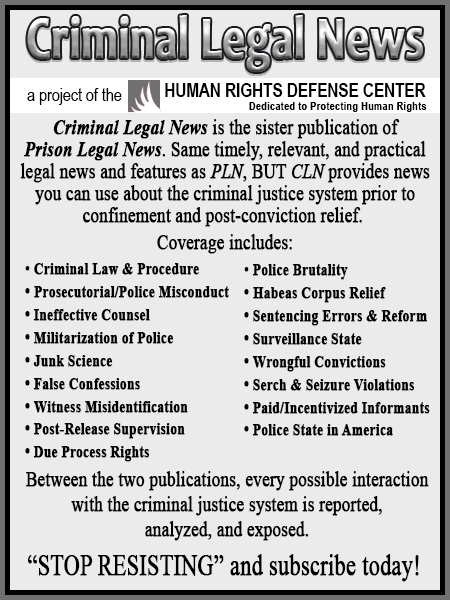

Landlords often demand first month's rent, last month's rent and a security deposit, a significant financial hurdle for those starting from scratch financially. Some halfway houses charge rents that absorb most of a resident's income, making saving difficult, said Alex Friedmann, associate director of Human Rights Defense Center and managing editor of Prison Legal News.

Nashville's shortage of affordable housing units for rent is projected to rise to nearly 31,000 by 2025 if more action is not taken for low-income residents, according to a 2017 city report.

While the affordable housing issue is a much-discussed issue in Nashville, policy discussions rarely focus on those with conviction histories, Kirkland said.

"It is a level of need and destitution that people face when they first get out that would be hard for anyone to deal and move through," Kirkland said. "That is the reality that people face when they get out, when they don’t have money or an I.D., and they are determined to live well and work and make their way."

Project Return advises individuals to ask if a conviction history will interfere before they pay an application fee. If they wait until further in the process, they risk losing money on each application, Kirkland said.

Tennessee has a 47 percent recidivism rate. The two main factors influencing recidivism are jobs and housing, so creating more housing options could help individuals avoid re-offending, Friedmann said.

"It’s a very significant issue," Friedmann said. "If we want less crime and recidivism, then it is part of our responsibility as a community to ensure that people coming out of prison at least have the opportunity to find housing and are not completely excluded from the housing market."

Project Return's PRO Housing program relies on a $284,000 grant from a Tennessee Housing Development Agency program that does not receive tax dollars, and two other grants have come from Nashville's Barnes Housing Trust Fund. PRO Housing also has access to low-interest loans for nonprofits creating affordable housing.

While Sledge was living with a friend's family in North Nashville, Project Return helped him develop a savings plan and showed him one of their own properties.

The property that been rehabbed by a team from one of Project Return's employment programs that trains those working on a construction certification. They installed dry wall, painted and worked on the floors.

“We are a duplex on a nice residential street,” Kirkland said. “We get there and immediately upgrade the property and have a mindset about really being the prettiest house on the block. That is how we are showing up.”

Sledge pays $600 a month for his home and has been steadily furnishing his living room.

"The first time I walked in here, I said to myself, 'Mac, you did it. You’re here,'" he said. "I could visualize things in here although there was nothing but walls. I took pictures of every room."

For nearly two years, Sledge has worked at Advanced Plating, a chrome and powdered coating manufacturer in Nashville. To punch the clock at 5 a.m., he usually wakes up at 3:20 a.m. He tries to work as much overtime as he can to build his savings for car repairs and for a down payment he hopes to make on a home of his own one day. In the meantime, he is happy to be in his own rental.

"It was an extremely good feeling to know that McArthur has his own," Sledge said. "He doesn’t have to rely on anyone when it comes to housing. I can pay for whatever it is I want to have in here."