Bill calls for dramatic rewrite of New Mexico Inspection of Public Records Act

A sophomore lawmaker has filed a bill proposing a dramatic rewrite of New Mexico’s public records law that critics warn would have an alarming effect on government transparency and accountability.

The measure would create dozens of new exemptions to the Inspection of Public Records Act, giving state and local government agencies broader authority to refuse to provide requested records.

Rep. Kathleen Cate, D-Rio Rancho, said she doesn’t expect the measure to become law but wanted to start a discussion.

“IPRA is not broken, but it needs to be managed,” she said in an interview.

House Bill 139 proposes allowing agencies to charge for time spent locating records, deny requests they are too busy to fill and refuse to provide information to requesters deemed “vexatious” for up to three years, among other things.

Cate said intent of the legislation is to provide relief for municipal and county governments overwhelmed by the demands of keeping up with records requests.

She sponsored it at the request of Sandoval County, she added.

“Sandoval County, as well as many other counties and municipalities have been inundated with frivolous and redundant IPRA requests which has necessitated the hiring of additional personnel and additional costs without any additional funding,” she wrote in an email.

“I am fully supportive of the public’s right to access and review governmental records,” she wrote. “This bill will not abridge that right.”

Open government and civil rights advocates disagreed, telling The New Mexican the legislation, as written, would eviscerate the Inspection of Public Records Act.

“HB 139 represents a dangerous gutting of critical transparency law in our state,” Leon Howard, interim executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of New Mexico, wrote in an email.

“The legislation would usher in an era in which access to information carries a hefty price tag and government secrecy is the norm. This is a moment in history in which we need to be bolstering transparency, not undercutting it,” he added.

A ‘problematic’ definition

Cate defended the 44-page proposal — which she said was brought to her by Sandoval County Attorney Michael Eshleman — but didn’t seem familiar with all of its provisions.

The lawmaker said the intended purpose of the bill is to “very surgically” address issues with the public records law — with a primary focus on “manual labor, expenses and copying,” and she insisted nothing in the bill would hinder transparency. Critics, however, pointed to multiple clauses they said prove otherwise.

“The bill contains over 40 pages of exceptions to what records the public may view and methods by which the government can avoid complying with a person’s request to inspect public records,” the Foundation for Open Government said in a statement.

“This alarming attempt to upheave New Mexico’s long-standing transparency law should be vigorously opposed by all who believe in government transparency and accountability,” the organization continued.

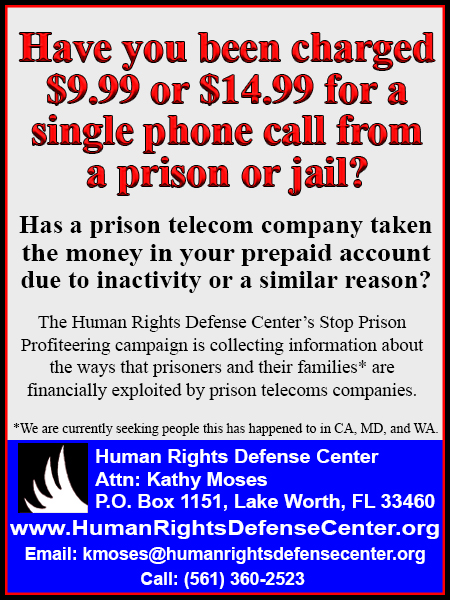

“I reviewed the bill, and it seems aimed at a wholesale gutting of the IPRA and pretty much ending transparency” in New Mexico, Human Rights Defense Center Director Paul Wright wrote in an email.

Of particular concern, he said, is the bill’s definition of “person” to exclude “individuals incarcerated in a correctional facility.”

“Any lawful definition of a ‘person’ that excludes some people is problematic for what should be obvious reasons,” Lavin wrote.

Cate conceded there are “issues with that section.” However, she added, that’s what the legislative process is for — to refine proposed laws.

“I want this bill to be part of a discussion that we need to review [the IPRA] process,” she said. The result could be no change to the law but with an appropriation added, she said.

HB 139 has been referred to the House Government, Elections and Indian Affairs Committee and the House Judiciary Committee.

Cate acknowledged the bill hasn’t been fully vetted by the Legislative Finance Committee.

“LFC said the bill is so dense it would take like four months to vet it, so they wouldn’t get it vetted in time,” she said.

Cate has heard another IPRA-related bill is expected to be introduced — which she said points to a need to overhaul the statute. If it’s better than hers, she said, she’d be willing to drop HB 139 and back it.

More proposed changes

New Mexico Counties Director Joy Esparsen said her organization also has concerns about the ability of public entities to keep up with the volume of IPRA requests that pour into government offices daily — and with an uptick in abuse of the records process.

After consulting with the Foundation for Open Government, her organization has elected to join the New Mexico Municipal League in supporting a not-yet-filed bill that will take a more “targeted approach” to reforming the law, she said.

Rep. Christine Chandler, D-Los Alamos, is expected to sponsor the bill. Chandler could not be reached for comment Friday.

Esparsen said the new bill will include the following proposed changes to IPRA, including some aimed at how public information is used:

- A requirement that public agencies be notified of alleged violations before legal action is taken and allowed to remedy the problems within 15 days.

- A two-year statute of limitations for filing complaints related to IPRA violations.

- A provision allowing records custodians to impose fees for requests to use records for commercial purposes and to impose fees of up to $30 per hour, after the first hour, for commercial requests.

- A prohibition on using law enforcement records to solicit victims or their relatives.

The bill also will propose the establishment of a committee to study an administrative appeals process “to resolve IPRA disputes efficiently,” according to Esparsen, and would call for “enforcement actions against requestors who violate IPRA.”

Esparsen pointed to a 2024 Municipal League report titled “IPRA in Action” as the basis for many of the changes New Mexico Counties and the Municipal League support.

Local governments have increased the number of staff dedicated to processing IPRA requests, resulting in cost increases of about 70%, the report says.

The current law also raises privacy concerns.

“Because New Mexico’s IPRA law largely does not exempt records related to juveniles and victims of crimes, the privacy and security of these individuals may be jeopardized in some records requests,” the report says.

HB 139 ‘goes too far’

Former Albuquerque City Councilor Pat Davis — now a publisher of multiple media outlets — said he’s seen the issues from both sides and thinks government should approach the issue with an eye toward making records more available, not less.

“While it is true that the digital revolution has created many, many more records of how our governments operate, it has also provided more tools to compile, review and respond to public requests more efficiently,” he wrote in an email. “More and more we are seeing that less-tech savvy counties and municipalities are unable to keep up.

“Instead of shielding more of what happens out of the public eye,” he added, “the legislature could solve this problem by resourcing city clerks and records custodians with tools to upgrade their digital capacity for record keeping and requests.”

When it comes to the privacy issues, Davis wrote: “I think we all have anxiety about the amount of our personal data available in public, but [HB 139] goes too far.”

Davis, whose media properties include the Sandoval Signpost and Corrales Comment, both in Cate’s district, as well as the Santa Fe Reporter, described some ways the news media use public records that should be protected:

“I want my local newspaper reporter to be able to see if residents from two different neighborhoods are getting the same medical services from the fire department. I want to know which water utility users waste the most water. This bill would shield all of that information — and more — from public view and that invites mischief and misspending of the public’s hard-earned tax dollars.”