Prison Legal News v. Secretary, Florida Dept. of Corrections Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

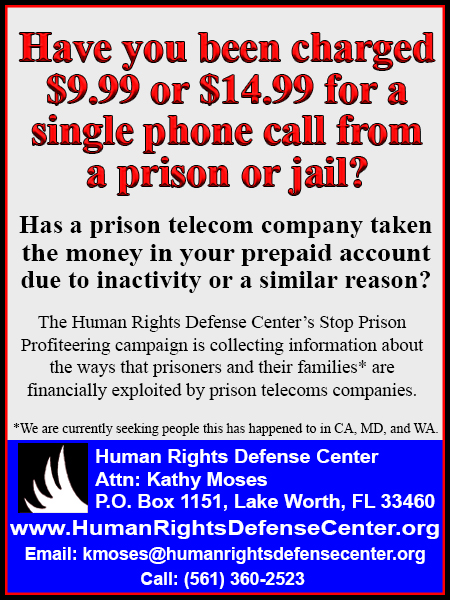

No. ______ In the Supreme Court of the United States ________________ PRISON LEGAL NEWS, v. Petitioner, SECRETARY, FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS, ________________ Respondent. On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit ________________ PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI ________________ MICHAEL H. MCGINLEY DECHERT LLP 1900 K Street, NW Washington, DC 20006 (202) 261-3300 PAUL D. CLEMENT Counsel of Record KIRKLAND & ELLIS LLP 655 Fifteenth Street, NW Washington, DC 20005 (202) 879-5000 paul.clement@kirkland.com Counsel for Petitioner (Additional Counsel Listed on Inside Cover) September 14, 2018 ROGER A. DIXON DECHERT LLP 2929 Arch Street Philadelphia, PA 19104 (215) 994-4000 LINDSAY E. RAY DECHERT LLP 1095 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10036 (212) 698-3500 SABARISH NEELAKANTA MASIMBA MUTAMBA DANIEL MARSHALL HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENSE CENTER P.O. Box 1151 Lake Worth, FL 33460 (561) 360-2523 DEBORAH GOLDEN HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENSE CENTER 316 F Street, NW, #107 Washington, DC 20002 (202) 543-8100 DANTE P. TREVISANI RANDALL C. BERG, JR. FLORIDA JUSTICE INSTITUTE, INC. 100 SE Second Street Suite 3750 Miami, FL 33131 (303) 358-2081 Counsel for Petitioner QUESTION PRESENTED Petitioner produces an award-winning monthly publication, Prison Legal News, featuring content directed to the specialized interests of inmates, including unlawful prison practices and litigation clarifying inmates’ civil rights. Despite allowing the magazine into its facilities for nearly two decades without any resulting security threats, the Florida Department of Corrections (FDOC) has banned every issue of Prison Legal News since 2009, ostensibly based on security concerns with the publication’s advertising content. The FDOC’s censorship is a national outlier—neither the federal Bureau of Prisons nor any other state or county prison system bans Prison Legal News based on its advertisements. And the FDOC has not pointed to concrete evidence of security problems either in the prison systems that allow Prison Legal News or even in Florida during the many years the publication was not censored. Nor has FDOC pointed to any unique characteristic that would explain why no other prison system shares its concerns. In conflict with this Court’s longstanding precedents and decisions from other circuits, the decision below upheld Florida’s blanket ban on Prison Legal News by blindly deferring to the FDOC’s unsubstantiated security concerns and granting virtually no weight to the First Amendment rights of petitioner, inmates or advertisers. The question presented is: Whether the Florida Department of Corrections’ blanket ban of Prison Legal News violates Petitioner’s First Amendment right to free speech and a free press. ii PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING Petitioner Prison Legal News was plaintiff in the district court and appellee and cross-appellant before the Eleventh Circuit. Respondent Secretary of the Florida Department of Corrections was defendant in the district court and appellant and cross-appellee before the Eleventh Circuit. iii CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT Prison Legal News is a project of the Human Rights Defense Center, Inc., a not-for-profit charitable corporation. No publicly held corporation owns 10% or more of its stock. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS QUESTION PRESENTED .......................................... i PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING ........................... ii CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT ........... iii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ...................................... vi PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI ................ 1 OPINIONS BELOW ................................................... 3 JURISDICTION ......................................................... 3 CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED...................................... 3 STATEMENT OF THE CASE ................................... 4 I. Background .......................................................... 4 A. Prison Legal News ........................................ 4 B. FDOC’s Admissible Reading Material Rule ............................................................... 6 C. Previous Litigation by Prison Legal News Over the FDOC’s Admissible Reading Material Rule ................................................ 9 D. District Court Proceedings and Decision .. 11 E. Eleventh Circuit Decision .......................... 12 REASONS FOR GRANTING THE PETITION....... 17 I. The Eleventh Circuit’s Decision Conflicts With This Court’s Precedents ........................... 18 A. This Court’s Precedents Recognize That First Amendment Rights Are Not Extinguished Within Prison Walls And That Outlying Policies Like the FDOC’s Ban Demand Closer Scrutiny .................... 18 v B. Contrary to this Court’s Precedents, the Eleventh Circuit Granted Complete Deference to Florida Prison Administrators That Made It Impossible for Petitioner to Succeed ............................ 20 C. The Eleventh Circuit’s Decision Conflicts With Other Circuits’ Faithful Application of This Court’s Decisions ............................ 24 II. A Correct Application of this Court’s Precedents Would Require Relief For Petition ............................................................................ 28 III. The Eleventh Circuit’s Decision Is An Invitation And A Roadmap For Other Jurisdictions To Curtail Important First Amendment Freedoms ...................................... 32 CONCLUSION ......................................................... 34 APPENDIX Appendix A Opinion, United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, Prison Legal News v. Secretary, Fla. Dep’t. of Corrections, No. 15-14220 (May 17, 2018) ...................... App-1 Appendix B Amended Order, United States District Court for the Northern District of Florida, Prison Legal News v. Jones, No. 4:12cv239-MW/CAS (Oct. 5, 2015) .............................................. App-48 Appendix C Relevant Statutory Provision.................. App-112 Fla. Admin. Code R. 33-501.401(3) .. App-112 vi TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Cases Beard v. Banks, 548 U.S. 521 (2006) ........................................ passim Bell v. Wolfish, 441 U.S. 520 (1979) ................................................ 19 Brown v. Phillips, 801 F.3d 849 (7th Cir. 2015).................................. 26 Cal. First Amendment Coal. v. Woodford, 299 F.3d 868 (9th Cir. 2002)............................ 25, 26 Holt v. Hobbs, 135 S. Ct. 853 (2015)........................................ 20, 31 Overton v. Bazzetta, 539 U.S. 126 (2003) ................................................ 20 Prison Legal News v. Cook, 238 F.3d 1145 (9th Cir. 2001)............................ 8, 24 Prison Legal News v. McDonough, 200 F. App’x 873 (11th Cir. 2006) ......................... 10 Procunier v. Martinez, 416 U.S. 396 (1974) .................................... 18, 20, 31 Ramirez v. Pugh, 379 F.3d 122 (3d Cir. 2004) ................................... 26 Reed v. Town of Gilbert, 135 S. Ct. 2218 (2015)............................................ 29 Thornburgh v. Abbott, 490 U.S. 401 (1989) ........................................ passim Turner v. Cain, 647 F. App’x 357 (5th Cir. 2016) ........................... 27 Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78 (1987) ................................ 13, 14, 19, 21 vii Wolf v. Ashcroft, 297 F.3d 305 (3d Cir. 2002) ................................... 27 Wolff v. McDonnell, 418 U.S. 539 (1974) ................................................ 19 Statutes Fla. Admin. Code R.33-210.101(5) ............................. 7 Fla. Admin. Code R.33-501.401 ............................. 6, 7 Fla. Admin. Code R.33-501.401(3) ................... 7, 8, 11 Fla. Admin. Code R.33-501.401(4) ............................. 8 Fla. Admin. Code R.33-501.401(8) ............................. 7 Fla. Admin. Code R.33-501.401(14) ........................... 7 Other Authorities John E. Dannenberg, U.S. Supreme Court Upholds $625,000 Judgment for Female Prisoner Molested by Ohio Prison Guard (Mar. 15, 2011), https://bit.ly/2NTJQ90 .................. 5 Defs’ Resp. in Opp. to Pltf’s Mot. for Prel. Inj., Human Rights Defense Center v. Sw. Va. Reg. Jail Auth., No. 1:18-cv-13 (W.D. Va. May 29, 2018) .................................................. 33 Derek Gilna, Supreme Court Reverses Criminal Conviction for Racial Bias by Juror (Mar. 31, 2017), https://bit.ly/2oITJeV ............................................... 5 Derek Gilna, Supreme Court Sets Aside Florida’s Death Penalty Sentencing Procedure (Feb. 2, 2016), https://bit.ly/2Nkww0y ............................................ 5 viii Emily Masters, By the numbers: New York’s prison population, Albany Times Union (Sept. 21, 2017), https://bit.ly/2loj2B6 ................... 15 David M. Reutter, Eleventh Circuit Affirms Injunction in Florida DOC Mental Health Conditions Pepper Spray Case, Prison Legal News (Feb. 15, 2011), https://bit.ly/2wsxDBC............................................. 5 David M. Reutter, Florida’s Department of Corrections: A Culture of Corruption, Abuse and Deaths, Prison Legal News (Feb. 2, 2016), https://bit.ly/2N1CX8H ................... 5 David M. Reutter, Record Number of Florida Prisoners Died in 2016, 2017, Prison Legal News (Jan. 31, 2018), https://bit.ly/2PU46J9 .............................................. 5 Kent A. Russell, Habeas Hints: 2012 Supreme Court Habeas Highights: Plea Bargaining Cases (Sept. 15, 2012), https://bit.ly/2NkRyfp .............................................. 5 Order, Prison Legal News v. Crosby, No. 3:04-cv-14-JHM-TEM (M.D. Fla. July 28, 2005), Doc. 87 ......................................................... 10 PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI The Florida Department of Corrections (FDOC), alone among the fifty states, the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), and every county jail in the nation, is violating Prison Legal News’ (PLN) First Amendment rights by confiscating every issue of its magazine based on the content of the publication’s advertisements. This broad restriction on PLN’s protected speech is neither logical nor necessary. For years, Florida allowed Prison Legal News to circulate in its prison system without incident. But in 2003, FDOC engaged in its first attempt at censorship, which prompted an earlier round of litigation. In 2005, in an effort to moot that earlier litigation, the FDOC briefly realigned itself with every penal institution in the nation in concluding that PLN’s publications do not pose a material security threat. But in 2009, the FDOC abruptly changed course and has censored every subsequent issue of PLN. Although it purports to justify this censorship of Prison Legal News on security concerns with its advertising, the FDOC has never presented any evidence that the content of those advertisements actually caused any such breaches of security during the 55 months FDOC relented in its censorship. Nor has it ever shown that security improved once FDOC renewed its ban. Nor has it identified any unique problems faced by Florida penal institutions that justify its alone-in-the-nation position. Instead, it relied entirely on the censor’s refrain that completely banning PLN “certainly help[s]” prevent “potential security threats.” 2 But this Court has never allowed such an unsupported, self-serving assertion to justify a complete ban on the core free speech rights of either inmates or the press. Instead, the Court has long reminded lower courts that prison walls do not form a barrier against free speech or free press rights. Publishers, reporters, and advertisers have a constitutionally protected interest in communicating with prisoners, and prisoners have a right to receive those communications. These protections are all the more important when the publication at issue is uniquely designed to inform prisoners of their legal rights, and a prison’s decision to silence that speech is all the more suspect when it is applied in a blanket manner to the entire incarcerated population based on bare assertions of security concerns without supporting evidence. While valid penological interests can justify intrusions on speech within prison walls that would not be permissible outside them, the Court has always required a nexus between valid penological interests and the prison’s intrusions on free speech. And it has never accepted mere conjecture as sufficient to support this kind of blanket ban. The Eleventh Circuit’s decision is an outlier ruling upholding an outlier policy. By ratcheting up the deference owed to prison officials and ratcheting down the quantum of evidence those officials must supply to justify wholesale censorship of core free speech rights, the Eleventh Circuit’s decision is grossly out of step with this Court’s precedents. And it is flatly inconsistent with the rulings of other circuits that have faithfully applied this Court’s decisions to reject censorship of the “core protected speech” that Prison Legal News offers in its 3 magazines. Although the censorship of PLN has been limited to Florida, the threat to First Amendment rights if the decision is left standing certainly does not end there. The Eleventh Circuit’s decision provides both an invitation and a roadmap to silence PLN and any other publication that seeks to inform prisoners of their rights or to expose unlawful conduct by prison officials. There is little doubt that the ruling below will prompt other prison systems to follow Florida’s lead. Rather than let that trend blossom into further censorship, this Court should step in now to vindicate the First Amendment. OPINIONS BELOW The Opinion of the Eleventh Circuit affirming the judgments of the district court is reported at 890 F.3d 954 and reproduced at App.1-47. The District Court’s Order entering judgment for Respondent on Petitioner’s First Amendment claim and entering judgment for Petitioner on its Fourteenth Amendment claim is unreported and reproduced at App.48-112. JURISDICTION The Eleventh Circuit entered its opinion on May 17, 2018. On August 3, 2018, Justice Thomas granted an extension to September 14, 2018 to file this petition for writ of certiorari. Dkt. No. 18A126. This Court has jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1). CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED The First Amendment provides: Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the 4 freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances. Relevant portions of the FDOC’s Rule on “Admissible Reading Material,” Fla. Admin. Code R. 33-501.401(3), is reproduced in the Appendix. STATEMENT OF THE CASE I. Background A. Prison Legal News Petitioner Prison Legal News (PLN) exists to advance and protect important constitutional liberties. It is a project of the Human Rights Defense Center, Inc., a not-for-profit, Florida-based corporation dedicated to the protection and advancement of human rights. For nearly 30 years, PLN has published the award-winning Prison Legal News, a monthly magazine of prison news and analysis, featuring content informing inmates of unconstitutional prison practices and educating them about their civil rights under the law. By publishing Prison Legal News, PLN achieves its core missions of public education, advocacy, and outreach on behalf of, and for the purpose of assisting, prisoners who seek to enforce their constitutional and basic human rights in our nation’s criminal justice system. To further PLN’s mission, Prison Legal News contains articles by legal scholars, attorneys, prisoners, and news wire services, presenting news and analysis primarily of legal developments affecting incarcerated people and their families, as well as investigative reports and political and news 5 commentary largely critical of the prison system. Indeed, during the FDOC’s ban on Prison Legal News, the magazine has published dozens of reports exposing corruption and abuses in Florida’s penal system. See, e.g., David M. Reutter, Record Number of Florida Prisoners Died in 2016, 2017, Prison Legal News (Jan. 31, 2018), https://bit.ly/2PU46J9; David M. Reutter, Florida’s Department of Corrections: A Culture of Corruption, Abuse and Deaths, Prison Legal News (Feb. 2, 2016), https://bit.ly/2N1CX8H; David M. Reutter, Eleventh Circuit Affirms Injunction in Florida DOC Mental Health Conditions Pepper Spray Case, Prison Legal News (Feb. 15, 2011), https://bit.ly/2wsxDBC. Likewise, during the course of FDOC’s ban, Prison Legal News has featured numerous stories on decisions of this Court of particular interest to inmates. See, e.g., Derek Gilna, Supreme Court Reverses Criminal Conviction for Racial Bias by Juror (Mar. 31, 2017), https://bit.ly/2oITJeV; Derek Gilna, Supreme Court Sets Aside Florida’s Death Penalty Sentencing Procedure (Feb. 2, 2016), https://bit.ly/2Nkww0y; Kent A. Russell, Habeas Hints: 2012 Supreme Court Habeas Highights: Plea Bargaining Cases (Sept. 15, 2012), https://bit.ly/2NkRyfp; John E. Dannenberg, U.S. Supreme Court Upholds $625,000 Judgment for Female Prisoner Molested by Ohio Prison Guard (Mar. 15, 2011), https://bit.ly/2NTJQ90. Prison Legal News has a monthly circulation of approximately 7,000 printed copies and has subscribers in the United States and abroad, including incarcerated subscribers in all 50 State correctional 6 systems, the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), and numerous detention centers and county jails throughout the country. Like most news publications, PLN subsists by including advertisements in Prison Legal News. Advertisers interested in buying advertising space in Prison Legal News include some law firms specializing in prisoner litigation and schools offering inmate correspondence courses, but they also include pen pal services, less expensive inmate phone services, and cash-for-stamps services. It is undisputed that printing a Florida-only edition without the latter category of advertisements would be cost-prohibitive for PLN. See App.35 Nor has the FDOC ever indicated that it would actually deliver such a Florida-specific edition. B. FDOC’s Admissible Reading Material Rule The FDOC has adopted a number of regulations governing Florida’s prisons. The rule at issue here, the “Admissible Reading Material” Rule, addresses prisoner mail. See Fla. Admin. Code R.33-501.401. It allows prison officials to screen incoming mail addressed to prisoners, and it directs these officials to impound any publication that is found to violate any one of thirteen criteria. Relevant to this case, the current Rule requires that a publication be impounded if: It contains an advertisement promoting any of the following where the advertisement is the focus of, rather than being incidental to, the publication or the advertising is prominent or prevalent throughout the publication. 7 1. Three-way calling services; 2. Pen pal services; 3. The purchase of products or services with postage stamps; or 4. Conducting a business or profession while incarcerated. [or] It otherwise presents a threat to the security, order or rehabilitative objectives of the correctional system or the safety of any person. Fla. Admin. Code R.33-501.401(3)(l), (m). In Florida prisons, officials screen incoming prisoner mail for compliance with these regulations. Prison mailroom staff open every piece of non-legal mail, including publications like Prison Legal News, and search for contraband and prohibited communications. Fla. Admin. Code R.33-210.101(5), 33-501.401. If a mailroom employee believes that a publication violates the “Admissible Reading Material” Rule, he or she impounds it. See Fla. Admin. Code R.33-501.401(8). The Literature Review Committee (LRC), which is staffed by three FDOC employees, meets periodically to decide whether to affirm or overturn such impoundment decisions. Fla. Admin. Code R.33501.401(14). However, the LRC only reviews the pages of the impounded publication that contain the offending advertisements—the LRC does not see or review the entire publication, even if the prominence or prevalence of disfavored advertising “throughout the publication” formed the basis of the impoundment 8 decision. If an issue of a publication has been rejected in the past, the LRC automatically rejects the publication each future time it comes before the LRC. Fla. Admin. Code R.33-501.401(3)-(4). Since September 2009, the FDOC has impounded every single issue of Prison Legal News it has received. Most of the issues have been rejected pursuant to Fla. Admin. Code R.33-501.401(3)(l), on the basis that certain problematic advertising is “prominent or prevalent throughout the publication,” even though the LRC reviewed only the pages containing the advertising in question. As a result of this process, the number of PLN’s subscribers in Florida prisons has dropped precipitously. Should the FDOC’s aggressive policy continue, the number of Florida prisonsubscribers will soon be zero. The FDOC’s censorship of Prison Legal News is a national outlier. To PLN’s knowledge, based on its almost three decade’s experience of having subscribers in the federal system and all 50 State prison systems, Florida is currently the only State in the union that completely censors the magazine because of its advertising content.1 No other State corrections agency, nor the BOP, nor any detention center nor county jail (including all 67 county jails in Florida) considers it necessary to censor Prison Legal News based solely on its advertisements. Even privateAt various times, other states have impounded Prison Legal News for reasons other than its advertising content, many times based on blanket prohibitions that applied across the board to other publications. PLN has frequently mounted successful challenges to those policies, as explained below. See, e.g., Prison Legal News v. Cook, 238 F.3d 1145 (9th Cir. 2001). 1 9 prison censorship at Florida has occurred only at the behest of the FDOC; none of the private prison operators ban Prison Legal News in their out-of-state facilities based on the magazine’s advertisements.2 C. Previous Litigation by Prison Legal News Over the FDOC’s Admissible Reading Material Rule From PLN’s founding in 1990 until 2003, the publisher successfully distributed Prison Legal News to Florida’s prison population. In February 2003, the FDOC began censoring Prison Legal News based on its advertising content. PLN sued, raising free speech and due process claims under the First and Fourteenth Amendments. While the suit was pending in March 2005, the FDOC amended Rule 33-501.401 to clarify that publications would not be rejected for advertising content that is merely incidental to, rather than the focus of, the publication. App.52. Based on this change, the FDOC insisted that it would no longer censor Prison Legal News. After the amendment, and throughout the remainder of that phase of the litigation, the FDOC refrained from censoring Prison Legal News and successfully delivered it to Florida prisoners. In addition, the FDOC delivered the hundreds of Prison Legal News issues that it impounded during the 2003-2005 censorship period. 2 The GEO Group and Corrections Corporation of America, now known as CoreCivic, were initially co-defendants in the lower court proceedings but were subsequently dismissed from the suit pursuant to a settlement agreement that they reached with PLN. 10 The FDOC thus urged the court to dismiss PLN’s First Amendment claims as moot based on the policy change. The FDOC also informed the court that it no longer had any security concerns with PLN’s advertisements. Based on these representations, the trial court agreed that the claim had become moot, finding that “the FDOC ha[s] plenty of ways at its disposal to prevent the inmates from taking advantage of any illicit services offered in the advertisements, [and] its procedures and policies already ensure that publications such as PLN, which are not focused on such content, can be distributed to inmates without any substantial security concerns.” Order 13-14, Prison Legal News v. Crosby, No. 3:04-cv14-JHM-TEM (M.D. Fla. July 28, 2005), Doc. 87. The Eleventh Circuit affirmed that decision based on the same representations from the FDOC. Specifically, the Court of Appeals held that, “although the FDOC previously wavered on its decision to impound the magazine, it presented sufficient evidence to show that it has ‘no intent to ban PLN based solely on the advertising content at issue in th[e] case’ in the future.” Prison Legal News v. McDonough, 200 F. App’x 873, 878 (11th Cir. 2006). Relying on the FDOC’s assurances about how it would apply its new policy, the Eleventh Circuit had “no expectation that FDOC w[ould] resume the practice of impounding publications based on incidental advertisements.” Id. The FDOC has never alleged, let alone documented, that its delivery of Prison Legal News during the nearly two decades it allowed the magazine to circulate led to any security threats. 11 D. District Court Proceedings and Decision Only three years after securing dismissal of PLN’s first lawsuit, the FDOC resumed its censorship of Prison Legal News based on its advertising content. In 2009, the FDOC amended its Admissible Reading Material Rule to instruct prison officials to reject a publication if prohibited advertisements are “prominent or prevalent throughout the publication,” Fla. Admin. Code R.33-501.401(3)(l), and the FDOC reinstituted its blanket, state-wide ban of Prison Legal News. In November 2011, PLN again sued the FDOC. PLN challenged the FDOC’s censorship of PLN’s protected speech under the First and Fourteenth Amendments.3 PLN sought a declaratory judgment and a permanent injunction. After denying crossmotions for summary judgment, the district court held a four-day bench trial. The court upheld the FDOC’s censorship of PLN’s protected speech. Although the FDOC produced no evidence that Florida’s prisons had experienced any new security problems traceable to its decision to stop censoring Prison Legal News, the court broadly deferred to the FDOC’s claimed need to resume censorship. See App.90-92. And despite finding that PLN could not afford to publish its magazine without advertisements or publish a Florida-only version of Prison Legal News, the court found that PLN had 3 PLN also raised a due process claim, attacking the FDOC’s failure to provide adequate notice of its impoundment of Prison Legal News. The District Court ruled in PLN’s favor on that claim, and the Eleventh Circuit affirmed. 12 alternative means of expressing itself in Florida’s prisons. See App.92. The district court further concluded that the FDOC could not accommodate PLN’s rights without burdening prison resources or security concerns. See App.93-94. Instead of pointing to specific evidence supporting this conclusion, the court believed that Supreme Court precedent required it to defer to the “informed discretion of corrections officials.” App.93 (quoting Thornburgh v. Abbott, 490 U.S. 401, 418 (1989)). The district court found it “troubling” that no other prison system in the United States censors Prison Legal News for its advertising content, App.94, but declined to conclude that the FDOC’s de facto ban was an exaggerated response to its security concerns. The court noted the “many other worrisome facts uncovered at trial,” including the inherent vagueness of the Rule’s “prominent or prevalent” standard and the doubtful capability of the LRC to assess prevalence without reviewing the entire publication. App.95. Nevertheless, the court concluded that the FDOC’s uniform rejection of Prison Legal News suggested that the Rule could be applied intelligibly, and it considered itself constrained to uphold the FDOC’s practice of censoring PLN. See App.97. After the entry of final judgment, both parties appealed. E. Eleventh Circuit Decision The Eleventh Circuit affirmed the district court’s order in its entirety. Like the District Court, the Eleventh Circuit viewed itself as obliged to grant “‘wide-ranging’ and ‘substantial’ deference to the 13 decisions of prison administrators.” See App.20. The court noted the four factors this Court articulated in Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78 (1987), “[t]o balance judicial deference with ‘the need to protect constitutional rights.’” App.19 (quoting Turner, 482 U.S. at 85, 89). But after a brief nod to this Court’s requirement that there must be “more than a formalistic logical connection” between a prison regulation and a penological objective, App.19-20 (quoting Beard v. Banks, 548 U.S. 521, 535 (2006) (plurality)), the Eleventh Circuit deferred to prison officials on each Turner factor. In applying Turner, the Eleventh Circuit relied upon the conjecture of the FDOC’s expert witness. On the question of whether a rational connection existed between the FDOC’s impoundment decision and its security concerns, the court minimized the FDOC’s failure to present evidence that magazine advertisements had actually caused a security breach. See App.25-27. The court placed great weight on testimony that “the ads ‘create the possibility, [the] real possibility’ of inmates doing an end run around prison rules.” See App.29 (emphasis added). The court proceeded to approve the FDOC’s concerns about the specific prohibited advertisements in each instance, despite the lack of concrete evidence of an actual security threat. See App.32-33 (crediting testimony that the large number of cash-for-stamps ads proves that inmates are using those companies); App.33-34 (recounting testimony about what an inmate “could” do via a prisoner concierge service). In some instances, the court even inserted its own conjecture and speculation. See App.30 (speculating 14 that “internet-based phone technology” had worsened the three-way calling problem). The Eleventh Circuit also found—unaided by any systematic review or measurable criteria—that the advertisements at issue were “prominent or prevalent,” and therefore implicated the FDOC’s regulations. See App.13 n.7. Even after acknowledging that the advertisements were no more “prominent or prevalent” in 2009 as compared to 2005 when taking into account the fact that the average issue of Prison Legal News had increased to 64 pages from 48 pages, the Eleventh Circuit relied on the increased number of full-page advertisements to support the conclusion that the advertisements were sufficiently “prominent or prevalent.” Id. While crediting every speculation advanced by the FDOC, the Eleventh Circuit conversely ignored critical evidence undermining any supposed relationship between the FDOC’s censorship of Prison Legal News and its claimed penological interests. The court dismissed the fact that FDOC had not experienced any noticeable increase in relevant security threats from the 19 years of Prison Legal News issues it allowed into its institutions. And it ignored the lack of any evidence that the ban on Prison Legal News has led to any decrease in the number of related prison rule violations since 2009. Its treatment of the other Turner factors was similarly one-sided. The second Turner factor considers whether PLN had alternative means to exercise its right of access to prisoners. See Turner, 482 U.S. at 90. The Eleventh Circuit conceded that no alternative method existed for distributing Prison 15 Legal News to Florida inmates because it can neither publish Prison Legal News without advertising revenue nor publish a Florida-specific version of its nationally distributed publication. But the court stressed that PLN can distribute other, unrelated materials. See App.35-37. On the third Turner factor—which considers the impact on guards and other inmates of accommodating PLN’s constitutional rights—the panel again eschewed concrete evidence in favor of generalized, unsubstantiated concerns about increased cost and the “ripple effects” of information exchange among inmates. See App.37-38. Under the fourth Turner factor, the court was required to consider whether the FDOC’s response was exaggerated. Despite the undisputed evidence that no other penal institution in the Nation considers it necessary to ban Prison Legal News based on its advertisements, the Eleventh Circuit held that the FDOC’s chosen policy of unilateral censorship was a perfectly proportionate response to its concerns. To support its argument that Florida had many other alternative options at its disposal, PLN had presented measures used in other jurisdictions, such as New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision’s (DOCCS) practice of affixing a notice to each issue of Prison Legal News advising inmates that some of the services advertised are prohibited by prison regulations. The Eleventh Circuit sarcastically likened this practice to living in “la-la-land,” even though New York prison officials manage one of the most dangerous prison populations in the country. See Emily Masters, By the numbers: New York’s prison population, Albany Times Union (Sept. 21, 2017), https://bit.ly/2loj2B6 (noting that two 16 thirds of New York inmates have been convicted of violent crimes). Thus, without any actual explanation from FDOC as to why it alone amongst all prison systems must ban Prison Legal News in its entirety every month, the panel brushed aside alternatives successfully employed elsewhere and held that the FDOC’s approach was not overbroad. See App.39-42. Rather than credit any concrete, experience-based evidence, the court generically stated that “[t]here is no onesize-fits-all approach to prison management,” and “every institution faces different security problems and deals with those problems in different ways.” App.41. Concluding its Turner analysis, the panel underscored its extreme deference to FDOC’s concerns. After addressing all of the factors, the court noted that the FDOC’s witness “summed up the relationship between the impoundment of Prison Legal News and the [FDOC’s] prison security and public safety interests by stating that those rules ‘certainly help[]’ advance those interests.” App.42-43. That extremely low bar, the Court proclaimed, “[t]hat is all Turner requires.” App.43. And, in so declaring, the court made no mention of this Court’s most recent exhortation that courts should not favor “logical relation[s]” over “experience-based conclusion[s],” or the Court’s emphatic statement that “the deference owed prison authorities” does not “mak[e] it impossible for prisoners or others attacking a prison policy … ever to succeed.” Beard, 548 U.S. at 533, 535. 17 REASONS FOR GRANTING THE PETITION The Eleventh Circuit upheld Florida’s blanket ban on Prison Legal News only by affording blind deference to Florida prison officials, in direct conflict with this Court’s decisions and other circuits’ faithful application of those precedents. Rather than requiring an “experience-based” relationship between Florida’s security concerns and its censorship of core free speech rights, the Eleventh Circuit ignored the actual experience of prison officials in Florida and throughout the nation. While novel problems and policies may require a degree of speculation, here prison officials had the benefit of nearly two decades during which Florida allowed Prison Legal News into its institutions, along with the experience of every other prison system in the country. Deferring to speculation in the absence of experience-based demonstration of increased risks during the interregnum or decreased risks after censorship was re-imposed is the antithesis of what this Court’s precedents require and what meaningful protection of First Amendment rights demands. Indeed, rather than meaningfully balancing the state’s penological interests against PLN’s constitutional rights, the Eleventh Circuit’s reasoning weighted the scales in a manner that made it “impossible for” any publisher “ever to succeed.” Beard, 548 U.S. at 535. While Florida’s policy and the Eleventh Circuit’s reasoning currently stand alone, there is already reason to believe that they are in the process of being replicated by other prisons and other courts. Rather than let this free speech violation metastasize, the Court should step in now to decide this important question and 18 resolve the discord between the Eleventh Circuit’s decision and this Court’s precedents. I. The Eleventh Circuit’s Decision Conflicts With This Court’s Precedents. A. This Court’s Precedents Recognize That First Amendment Rights Are Not Extinguished Within Prison Walls And That Outlying Policies Like the FDOC’s Ban Demand Closer Scrutiny. The FDOC’s censorship of Prison Legal News clearly impinges on PLN’s core First Amendment rights, as incorporated against the States by the Fourteenth Amendment. This Court has made it abundantly clear that prisons and First Amendment values are compatible. That is particularly true when it comes to the Free Speech and Free Press rights of publishers outside of prison walls who seek to include inmates within their audience. “[T]here is no question that publishers who wish to communicate with those who, through subscription, willingly seek their point of view have a legitimate First Amendment interest in access to prisoners.” Thornburgh, 490 U.S. at 408. As a result, prison walls do not “bar free citizens from exercising their own constitutional rights by reaching out to those on the ‘inside.’” Id. at 407. On the contrary, those seeking to communicate with prisoners enjoy “a protection against unjustified governmental interference with the intended communication.” Procunier v. Martinez, 416 U.S. 396, 408-09 (1974), overruled in part by Thornburgh, 490 U.S. 401. Nor are prisoners themselves without First Amendment rights, including the right to receive 19 Prison Legal News and similar publications. “It is equally certain that ‘[p]rison walls do not form a barrier separating prison inmates from the protections of the Constitution’ . . . .” Thornburgh, 490 U.S. at 407 (quoting Turner, 482 U.S. at 84). This Court has long made clear that “convicted prisoners do not forfeit all constitutional protections by reason of their conviction and confinement in prison.” Bell v. Wolfish, 441 U.S. 520, 545 (1979). “There is no iron curtain drawn between the Constitution and the prisons of this country.” Wolff v. McDonnell, 418 U.S. 539, 555-56 (1974). The nature of the First Amendment values at stake here demands greater scrutiny under this Court’s precedents. First Amendment rights are at their zenith, and their abridgment the most harmful, when a prison censors publications that inform inmates of their legal and civil rights and chronicle violations thereof. A publication like Prison Legal News is both uniquely useful to prisoners and, based on its content, a uniquely attractive target for censorship by prison officials. Indeed, during the last 9 years of censorship by the FDOC, Florida inmates were barred from reading the many articles in Prison Legal News regarding problems in their own prison system. See, e.g., supra at 5, 8. During the same period, Florida inmates were routinely denied access to articles explaining the practical implications of rulings of state and federal courts, including this Court, in terms that every inmate—and not just those immersed in the law—could understand. See, e.g., supra at 5. The particularly acute First Amendment interests at stake here weigh heavily in the balancing set forth in this Court’s precedents. 20 At the same time, the nature of the FDOC’s policy should also have triggered more demanding scrutiny under this Court’s case law. First, the reality that the FDOC applies its “prominent or prevalent” standard as a de facto ban should have triggered more searching scrutiny. See Overton v. Bazzetta, 539 U.S. 126, 134 (2003) (suggesting that, “if faced with evidence that [the State Department of Corrections’] regulation is treated as a de facto permanent ban,” the Court would not defer to the prison officials’ judgment). Moreover, the reality that the FDOC’s policy is a complete outlier and that the FDOC perceives security threats undetected by every other prison system in the nation also warrants closer scrutiny. See Martinez, 416 U.S. at 413 n.14; cf. Holt v. Hobbs, 135 S. Ct. 853 (2015). B. Contrary to this Court’s Precedents, the Eleventh Circuit Granted Complete Deference to Florida Prison Administrators That Made It Impossible for Petitioner to Succeed. This Court’s decisions have always emphasized the need to meaningfully balance First Amendment rights against prison systems’ valid penological interests. Thus, the interests of those who “bear [the] significant responsibility for defining the legitimate goals of a corrections system and for determining the most appropriate means to accomplish them,” Overton, 539 U.S. at 132, must be weighed against “the legitimate demands of those on the ‘outside’ who seek to enter that environment, in person or through the written word.” Thornburgh, 490 U.S. at 407. In ensuring that this balancing does not devolve into blind deference, the Court has emphasized that 21 judgments must be “experience-based,” Beard, 548 U.S. at 533, and not rely on speculation or involve “exaggerated response[s],” Thornburgh, 490 U.S. 418 (citing Turner, 482 U.S. at 90-91). And the Court has most recently emphasized that this framework ensures that the deck is not inexorably stacked against free speech rights within prison walls. See Beard, 548 U.S. at 535. The Eleventh Circuit eschewed this balanced approach in favor of blind deference to prison administrators. PLN set forth “experience-based” arguments for why the FDOC’s blanket ban was not justified by the FDOC’s stated security interests. Perhaps most significant, PLN pointed out that the FDOC had presented no evidence that security risks associated with the relevant advertisements had increased during the 55 months that the FDOC refrained from censoring Prison Legal News. Nor had the FDOC provided experience-based evidence that security threats decreased once its censorship was renewed. These omissions are particularly damning given the ample opportunities for the FDOC to point to experience-based problems during its own censorship interregnum and in the innumerable prisons and jails that do not censor Prison Legal News. Whatever the need for speculation when prison officials tackle a novel problem or ban a hazard that no prison officials tolerate, the need for experiencebased evidence is most pronounced when there are countless control groups (i.e., prison systems that allow the banned practice), including in Florida’s 67 county jails, federal and private prisons in Florida, and in the entire FDOC system itself. 22 Petitioner also emphasized that the FDOC resorted to censorship of Prison Legal News based on its advertisements, while tolerating primary conduct that posed a much greater and more direct threat to the FDOC’s stated concerns. For example, the FDOC banned Prison Legal News based in part on stampsfor-cash advertisements while allowing prisoners to amass large amounts of stamps.4 It disfavored advertisements of third-party telephone services while permitting calls to outside cell phone numbers that could not easily be tracked and could connect to three-way calls, despite purporting to limit prisoner calls to pre-approved lists of numbers. And, while expressing concerns about pen-pal advertisements, Florida prisoners are allowed to have pen pals. Moreover, PLN highlighted the fact that it does not directly provide any of the services in question. Finally, petitioner pointed out the difficulties with the FDOC’s “prominent or prevalent” standard. Not only was that unclear standard hopelessly standardless, it also reflects a judgment that some undefined quantum of advertisements for conduct forbidden to prisoners—whether three-way calling, cash-for-stamps, or vacation escapes to Aruba—is consistent with prison security. But the FDOC has never explained why it can tolerate some cash-forstamps advertisements sprinkled throughout a publication, for example, but must censor the entire publication when prison officials determine that those advertisements become “prominent or prevalent.” 4 The FDOC also declined to institute a system of posting envelopes using a postage meter and debiting the inmate’s account, thereby obviating the need for stamps altogether. 23 This not-too-much-disfavored-advertising standard is troubling not only because it suggests that the disfavored advertising is not incompatible with the demands of prison security but because it allows prison officials to target publications that are most focused on the needs of inmates as judged by both their editorial content and their advertising content. The Eleventh Circuit dismissed all of these experience-based arguments in favor of the FDOC’s speculation that banning Prison Legal News could “help” avoid the “real possibility” that the advertisements might assist prisoners in accomplishing the threats the FDOC identified. But Beard and the many cases that came before it emphasized that a prison’s infringement on First Amendment freedoms—especially those exercised by third-parties outside the prison walls—must bear “more than a formalistic logical connection between a regulation and a penological objective.” 548 U.S. at 535. Instead, there must be a rational connection based in experience and evidence beyond the mere say-so of self-interested prison officials. After all, if all that is needed to suppress First Amendment rights is a conviction by prison officials that less speech might help them do their jobs, then there is little left to this Court’s repeated assurance that constitutional rights are not surrendered at the prison gates. The Eleventh Circuit’s diluted standard is simply unfaithful to this Court’s precedents. Accordingly, this Court should step in to resolve this distortion of its precedents and remind lower courts that prison walls do not form an impenetrable barrier to critical First Amendment speech—especially publications by a free press intended to educate prisoners about everything from 24 this Court’s decisions to troubling abuses within prison systems and other news of interest to prisoners and their families. C. The Eleventh Circuit’s Decision Conflicts With Other Circuits’ Faithful Application of This Court’s Decisions. The Eleventh Circuit’s diluted approach conflicts not only with this Court’s precedents but also with decisions from other Circuits that have faithfully applied this Court’s precedents. In rejecting PLN’s argument that the FDOC must show an experiencebased connection between its censorship and its stated security concerns, the Eleventh Circuit concluded that “[r]equiring proof of such a correlation constitutes insufficient deference to the judgment of the prison authorities with respect to security needs.” App.26. However, following this Court’s decisions, from Turner to Thornburgh to Beard, many other Circuits have taken precisely the opposite view. In Prison Legal News v. Cook, 238 F.3d 1145 (9th Cir. 2001), for example, a challenge brought by PLN to Oregon’s ban on all “bulk mail,” the Ninth Circuit took a markedly different approach from that of the Eleventh Circuit here. Noting that Oregon was “the only prison system in the country that refuse[d] to deliver subscription non-profit organization standard mail,” id. at 1146-47, and that it would be “too expensive” for PLN to send its publications by firstclass mail, id. at 1148, the Ninth Circuit declined to defer to prison officials’ purported security concerns and upheld PLN’s First Amendment rights. The court emphasized that “[t]he speech at issue” in Prison Legal News “is core protected speech,” id. at 1149, 25 while rejecting the prison’s argument that PLN’s rights were not infringed because it could simply pay the higher postage rate. Although they assessed different prison policies, the Ninth and Eleventh Circuit’s analyses could not have been more different: While the Ninth Circuit found it relevant that Oregon’s policy was a national outlier, the Eleventh Circuit dismissed Florida’s alone-in-the-nation position as immaterial. While the Ninth Circuit was troubled by the fact that Oregon’s policy made it impractical for PLN to deliver its “core protected speech” to inmates, the Eleventh Circuit dismissed FDOC’s blanket censorship making it impossible for PLN to deliver its speech with the blithe suggestion that PLN’s other publications were uncensored. And while the Ninth Circuit refused to accept prison officials’ idiosyncratic and unsupported security rationales, the Eleventh Circuit viewed itself as bound to credit Florida’s conjecture and speculation. The consequence of these conflicting approaches is that Prison Legal News is free to exercise its First Amendment rights in Oregon, while it has been silenced in Florida. In other contexts, too, the Ninth Circuit has similarly rejected arguments based on conjecture and speculation, rather than concrete experience-based evidence. In California First Amendment Coalition v. Woodford, 299 F.3d 868 (9th Cir. 2002), the court addressed restrictions on the public’s access to view prisoner executions. Applying the Turner factors, the court rejected the prison’s security concerns—which were based, in part, on fear of retaliation against prison officials—as “pure speculation.” Id. at 882. While recognizing that prisons may anticipate 26 security threats and avoid them through rational policies, the court emphasized that prisons “must at a minimum supply some evidence that such potential problems are real, not imagined.” Id. And the court further concluded that the prison’s history of safety and its various loopholes to the policy fatally undermined its claimed security interest. Applying the same reasoning here, the Eleventh Circuit should have ruled for PLN, and its failure to do so is inconsistent with the Ninth Circuit’s holdings in California First Amendment Coalition. The Seventh Circuit has likewise required much greater proof than the Eleventh Circuit did here, and in much less compelling circumstances. In Brown v. Phillips, 801 F.3d 849 (7th Cir. 2015), the Seventh Circuit addressed claims by convicted sex offenders attacking a prison policy that prohibited them from accessing movies or video games with sexually explicit content. With obvious echoes of the FDOC’s position here, the prison officials in Brown had argued “that ‘common sense’ justifies prohibiting sex offenders from viewing sexually explicit materials.” Id. at 854. But the Seventh Circuit rejected that argument, holding that “some data is needed to connect” the prison’s goals “with a ban on” otherwise protected speech. Id.; see also Ramirez v. Pugh, 379 F.3d 122, 128 (3d Cir. 2004) (reversing dismissal of First Amendment challenge to blanket ban on sexually explicit magazines because mere assertion of rehabilitative effect was insufficient). Although the Seventh Circuit’s decision addressed a ban on sexually explicit material for specific prisoners, rather than a ban on Prison Legal News for all prisoners, its holding is only 27 more obvious and more forceful in this context.5 It cannot possibly be that sex offenders have greater rights to pornography than Prison Legal News has to distribute its award-winning publication containing articles on judicial decisions and other legal issues to any Florida prisoner. Many other Circuits have similarly adopted the same requirement that prison officials come forth with concrete, experience-based evidence to support infringements on protected speech. See, e.g., Turner v. Cain, 647 F. App’x 357, 367-68 (5th Cir. 2016) (holding that a warden’s failure to “produce[] evidence of any legitimate penological interest” in restricting parts of the plaintiff’s speech was enough for the plaintiff to prevail on the first element of his claim); Wolf v. Ashcroft, 297 F.3d 305, 308 (3d Cir. 2002) (holding that a prison must “‘demonstrate’ that the policy’s drafters ‘could rationally have seen a connection’ between the policy and the interests” through “more than a conclusory assertion” to succeed). The Eleventh Circuit’s explicit willingness to accept much less from the FDOC thus places it squarely out of step with a number of its sister Circuits and this Court. Rather than let that discord persist and threaten core The fact that the prisons in Brown did not categorically bar all sexually-explicit materials for all prisoners as fundamentally inconsistent with prison administration echoes the FDOC’s decision to not categorically bar all cash-for-stamps (and other disfavored) advertisements, but only when they appear in publications like Prison Legal News, where the disfavored advertisements are deemed to be prominent or prevalent. In both cases, the fact that the censored material is not categorically inconsistent with security concerns rationally increases the censor’s burden to explain the selective censorship. 5 28 free speech rights of important publications like Prison Legal News, this Court should grant review. II. A Correct Precedents Petition. Application of this Court’s Would Require Relief For Not only does the Eleventh Circuit’s decision distort this Court’s precedents and conflict with its sister Circuits’ faithful application of those decisions, but in doing so it validates a clearly unconstitutional ban on PLN’s First Amendment rights. Under this Court’s precedents, this should not have been a close case. The FDOC’s blanket ban of every single issue of Prison Legal News, at all times and to every subscriber, based on a prevalence of advertisements the FDOC will tolerate in small doses, is not rationally connected to its claimed security interests. The first Turner factor only weighs in favor of the governmental regulation when the regulation has a “valid, rational connection” to a legitimate governmental interest. App.25. As explained above, a “formalistic logical connection” is insufficient. Beard, 548 U.S. at 535. But that is the most the FDOC has offered, and it is all the Eleventh Circuit required. PLN set forth a number of reasons why the FDOC’s various loopholes for primary conduct and its toleration of advertisements for other conduct forbidden within prison walls—and even non-prevalent and nonprominent advertisements of the precise type that formed the basis for the exclusion of Prison Legal News—undermine its policy. And PLN highlighted the fact that the “experience-based” evidence cut strongly against the FDOC, which made no showing 29 that it experienced an uptick in security threats while allowing Prison Legal News into its prisons, or a downturn in such threats once it began censoring the publication again. Yet, the Eleventh Circuit was satisfied with the FDOC’s unadorned, self-serving statement that its ban “helps” avoid “potential” security threats related to certain advertisements. The second Turner factor considers whether the prison’s policy allows alternative means for the challenger to exercise its constitutional rights. It was undisputed that it would be cost-prohibitive for PLN, a non-profit nationally distributed publication, to produce a Florida-specific issue or to produce Prison Legal News without the problematic advertisements. Thus, there was no disagreement that PLN possesses no alternative means for delivering the awardwinning content of Prison Legal News to subscribers in Florida prisons. In the Eleventh Circuit’s view, though, that only made this factor a “close call.” And ultimately the court decided the factor in favor of the FDOC because PLN could potentially circulate its other publications instead of Prison Legal News as an “adequate alternative.” App.35-37. That analysis is deeply flawed. First, it is mere happenstance that petitioner even has other publications that it seeks to share with inmates. Given the cardinal command of the First Amendment not to discriminate between speakers, see Reed v. Town of Gilbert, 135 S. Ct. 2218 (2015), it cannot be right that the second Turner factor turns on whether a speaker has other, different publications that are not censored. In all events, the purposes of PLN’s other publications are different and thus their respective 30 content is naturally quite different. While its other publications are more generalized handbooks that furnish static advice on specific topics, Prison Legal News is the Human Rights Defense Center’s flagship monthly magazine, and it offers news on current events and information about recent legal developments such as new decisions of this Court or new findings of abuse in prison systems. It is markedly different speech aimed at different objectives. Under the FDOC’s draconian policy, there is simply no alternative means for PLN to deliver the content of Prison Legal News to its subscribers in Florida penal institutions. The Eleventh Circuit’s extreme deference to the FDOC’s claimed interests infected its assessment of Turner’s third factor as well. Accepting the FDOC’s unsupported assertions about the threats posed by Prison Legal News’ advertisements, the Eleventh Circuit held that the advertisements “give inmates the opportunity to use prohibited services, which creates security problems,” and that addressing those security problems would require the FDOC “to allocate more time, money, and personnel in an attempt to detect and prevent security problems engendered by the ads in the magazines.” App.37-38. But, as explained above, there was no evidence whatsoever that the FDOC had to bear any of those additional burdens during the 55-month interregnum between the FDOC’s censorship of Prison Legal News, let alone during the nearly two decades that Florida allowed Prison Legal News into its facilities. Nor did the FDOC set forth any evidence that any such burden was lifted when it banned the magazine again in 2009. 31 Finally, the Eleventh Circuit plainly erred in blessing the FDOC’s alone-in-the-Nation policy as a measured, rather than exaggerated response to its asserted (and entirely speculative) security concerns. The court’s mere observation that “there is no onesize-fits-all approach to prison management” is no substitute for a careful consideration of the treatment of Prison Legal News by every other penal institution in the country. App.41-42. Indeed, such careful judicial consideration is called for where, as here, the governmental entity curbing free press rights is the very entity that is the subject of critical reporting about abuses within its system. See supra 5. It would be one thing if Florida’s unique approach was designed to target some problem arising distinctly or uniquely in Florida’s prisons, but none of the FDOC’s purported security concerns are specific to Florida. The Eleventh Circuit’s failure to meaningfully consider alternatives was particularly evident in its dismissal of New York’s practice of affixing a warning to the front of Prison Legal News as living in “la la land.” This Court has long held that “the policies followed at other well-run institutions would be relevant to a determination of the need for a particular type of restriction.” Martinez, 416 U.S. at 413 n.14. And it has not hesitated to reject other states’ outlier intrusions on fundamental liberties premised on similarly speculative claims of prison security. Cf. Holt v. Hobbs, 135 S. Ct. 853 (2015) (“That so many other prisons allow inmates to grow beards while ensuring prison safety and security suggests that the Department could satisfy its security concerns through a means less restrictive than denying petitioner the exemption he seeks.”). A careful 32 consideration of the New York practice would underscore that it is an obvious alternative that more directly addresses the perceived concern of prison officials (New York’s disclaimer applies to any advertisement that proposes a transaction forbidden by prison rules, whether such advertisements are prevalent or prominent), and avoids the obvious prospect of selective censorship with respect to Florida’s vague “prominent or prevalent” standard. Especially when First Amendment values are at stake, deference to prison officials does not extend to allowing them to use a chainsaw, when a scalpel would do the trick. When judged against the New York policy, not to mention the complete lack of advertisement-based censorship or disclaimers in every other state prison system, the FDOC’s blanket ban is the archetype of an exaggerated response to a perceived problem. A properly balanced analysis of the Turner factors, under this Court’s precedents and the decisions of other circuits necessarily results in the conclusion that the FDOC’s exaggerated policy lacks a rational relation to its stated security concerns. Only by breaking from those precedents and blindly deferring to the FDOC’s asserted interests, could the Eleventh Circuit hold otherwise. III. The Eleventh Circuit’s Decision Is An Invitation And A Roadmap For Other Jurisdictions To Curtail Important First Amendment Freedoms. While the FDOC’s policy and the Eleventh Circuit’s decision currently stand alone as outliers, there is little doubt that they will serve as an 33 invitation and roadmap for other penal institutions that wish to curtail the important free speech rights of PLN or other publications. It is only a matter of time before other penal institutions intent on keeping the important content in Prison Legal News or other publications away from inmates replicate Florida’s policy. And, in the context of other restrictions, prisons have already begun to rely on the Eleventh Circuit’s excessively broad view of the deference owed to prison officials under this Court’s decisions. See, e.g., Defs’ Resp. in Opp. to Pltf’s Mot. for Prel. Inj. at 8, Human Rights Defense Center v. Sw. Va. Reg. Jail Auth., No. 1:18-cv-13 (W.D. Va. May 29, 2018) (“[I]n the case of First Amendment concerns, the Supreme Court ‘has not adopted a damn-the-deference, fullspeed-approach to First Amendment rights within prison walls.’” (quoting decision below)). The Eleventh Circuit’s decision has thus had an immediate, and predictable, impact in only a matter of months. That trend will undoubtedly grow if this Court denies review. Rather than let the Eleventh Circuit’s distortion of this Court’s precedents proliferate, the Court should step in and resolve this important question now. Even apart from its tendency to spread to other jurisdictions, the decision is important and merits this Court’s review. The decision undeniably means that thousands of FDOC inmates will not receive a publication designed to inform them of their legal right and of abuse within the FDOC system. It plainly paves the way for censorship of the First Amendment rights of the many more thousands of individuals currently detained within the confines of the Eleventh Circuit. And it harms the First Amendment rights of 34 PLN and others to reach this critical audience and inform them about legal developments outside of prison walls and illegal abuses within them. The decision plainly warrants plenary review. CONCLUSION The petition for writ of certiorari should be granted. Respectfully submitted, MICHAEL H. MCGINLEY DECHERT LLP 1900 K Street, NW Washington, DC 20006 (202) 261-3300 PAUL D. CLEMENT Counsel of Record KIRKLAND & ELLIS LLP 655 Fifteenth Street, NW Washington, DC 20005 (202) 879-5000 paul.clement@kirkland.com ROGER A. DIXON DECHERT LLP 2929 Arch Street Philadelphia, PA 19104 (215) 994-4000 LINDSAY E. RAY DECHERT LLP 1095 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10036 (212) 698-3500 SABARISH NEELAKANTA MASIMBA MUTAMBA DANIEL MARSHALL HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENSE CENTER P.O. Box 1151 Lake Worth, FL 33460 (561) 360-2523 DEBORAH GOLDEN HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENSE CENTER 316 F Street, NW, #107 Washington, DC 20002 (202) 543-8100 35 DANTE P. TREVISANI RANDALL C. BERG, JR. FLORIDA JUSTICE INSTITUTE, INC. 100 SE Second Street Suite 3750 Miami, FL 33131 (303) 358-2081 Counsel for Petitioner September 14, 2018