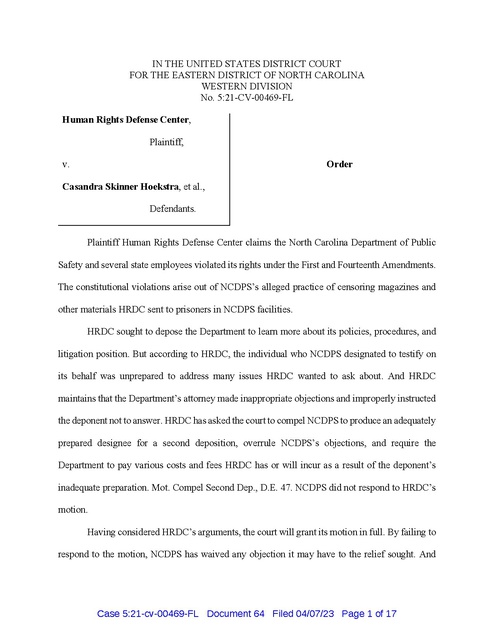

HRDC v. Ishee, et al., NC, Order Granting Motion to Compel, 2023

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA WESTERN DIVISION No. 5:21-CV-00469-FL Human Rights Defense Center, Plaintiff, Order v. Casandra Skinner Hoekstra, et al., Defendants. Plaintiff Human Rights Defense Center claims the North Carolina Department of Public Safety and several state employees violated its rights under the First and Fourteenth Amendments. The constitutional violations arise out of NCDPS’s alleged practice of censoring magazines and other materials HRDC sent to prisoners in NCDPS facilities. HRDC sought to depose the Department to learn more about its policies, procedures, and litigation position. But according to HRDC, the individual who NCDPS designated to testify on its behalf was unprepared to address many issues HRDC wanted to ask about. And HRDC maintains that the Department’s attorney made inappropriate objections and improperly instructed the deponent not to answer. HRDC has asked the court to compel NCDPS to produce an adequately prepared designee for a second deposition, overrule NCDPS’s objections, and require the Department to pay various costs and fees HRDC has or will incur as a result of the deponent’s inadequate preparation. Mot. Compel Second Dep., D.E. 47. NCDPS did not respond to HRDC’s motion. Having considered HRDC’s arguments, the court will grant its motion in full. By failing to respond to the motion, NCDPS has waived any objection it may have to the relief sought. And Case 5:21-cv-00469-FL Document 64 Filed 04/07/23 Page 1 of 17 even if the Department had responded, the record demonstrates that HRDC is entitled to the relief it seeks—NCDPS’s designee did not adequately prepare for the deposition, and its counsel’s objections and instructions not to answer were improper. I. Background This case arises out of HRDC’s allegations that NCDPS improperly censors magazines and other written materials that the Center wishes to send to prisoners housed in NCDPS facilities. Am. Compl. ¶ 1, D.E. 35. The Center also claims that the Department is violating its due process rights by not providing a mechanism through which it can challenge the Department’s decision to censor the publications. Id. ¶ 2. In late October 2022, HRDC’s attorneys emailed NCDPS’s counsel to discuss scheduling the Department’s deposition. Email from Ari Meltzer to James Trachtman & Shelby Boykin (Oct. 31, 2022, 3:30 p.m.) at 1–3, D.E 48–1. The Center suggested that the deposition take place on November 22, 2022, and listed potential deposition topics. Id. at 2. Four days later, NCDPS’s counsel responded that the Department was “not available for deposition on” the suggested date and was “unlikely to be available before the Thanksgiving holiday.” Email from Boykin to Meltzer & Trachtman (Nov. 3, 2022, 12:43 p.m.) at 1, D.E. 48–2. Counsel stated that she was “happy to inquire about a date after November 28, 2022” to hold the deposition. Id. That same day, HRDC asked NCDPS’s counsel to find out about taking the deposition on November 29, December 1, or December 2. Email from Meltzer to Boykin & Trachtman (Nov. 3, 2022, 5:49 p.m.) at 1, D.E. 48–3. After eight days passed without receiving a response, HRDC served a Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 30(b)(6) deposition notice requiring NCDPS to appear for a deposition on November 29. Dep. Notice, D.E. 48–4. The notice included 22 topics that HRDC wished to question NCDPS 2 Case 5:21-cv-00469-FL Document 64 Filed 04/07/23 Page 2 of 17 about. HRDC eventually served an amended deposition notice changing the deposition date to December 13, 2022, but keeping the same topics. Am. Deposition Notice, D.E. 48–5. NCDPS designated Loris Sutton, its Deputy Secretary for Internal Affairs and Intelligence Operations, to testify on its behalf. 1 When asked about her preparation for the deposition, Sutton responded that she had met with counsel before the deposition, exchanged “a number” of emails, and reviewed the policy governing the dissemination of written materials to prisoners. Dep. Tr. at 14:4–16, D.E. 48–6. She reviewed no other documents to prepare for the deposition. Id. at 14:17– 19. That level of preparation, however, left Sutton without information on many topics that HRDC wished to ask about. For example, while HRDC included “NCDPS’s answer to HRDC’s Complaint” as one of its areas of inquiry, Sutton was largely unable to explain why NCDPS denied various allegations. See, e.g., id. at 21:21–30:7. And although NCDPS was put on notice that it needed to designate someone to testify about its interrogatory responses, Sutton had not reviewed those responses. See, e.g., id. at 43:22–24. Similarly, even though the deposition notice identified the “actions” the Department took “to implement the Urbaniak Consent Decree” 2 as a topic, Sutton was unfamiliar with that document and had not prepared to testify about it. See id. at 136:17– 137:12. NCDPS apparently also designated a second individual to testify on its behalf. Mem. in Supp. at 2 n.1, D.E. 48. That individual’s testimony and preparedness do not appear to be at issue in this motion. 2 This consent decree—entered in consolidated cases Urbaniak v. Stanley, No. 5:06-CT-3135-FL (E.D.N.C.) and Allen v. Beck, 5:07-CT-3145-H (E.D.N.C.)—imposed several modifications to the North Carolina Department of Correction’s policy governing the receipt of publications by inmates. NCDOC became NCDPS. See Brown v. Hooks, No. 5:18-CV-00092-FDW, 2019 WL 4859101, at *2 (W.D.N.C. Oct. 1, 2019). Among other things, the consent decree requires NCDPS to uniformly apply its publication policy, notify North Carolina Prisoner Legal Services, Inc., of any proposed changes to the policy, and modify its Inmate Handbook to inform prisoners about their right to appeal the denial of any publication. See Stipulated Consent Decree at 2–4, Urbaniak, No. 5:06-CT3135-FL (E.D.N.C. Aug. 27, 2010), D.E. 133. 1 3 Case 5:21-cv-00469-FL Document 64 Filed 04/07/23 Page 3 of 17 Sutton’s lack of information extended to more substantive matters as well. In connection with the deposition topic seeking NCDPS’s rationale for rejecting various HRDC publications, the Center asked Sutton to identify the material within each publication that led to its rejection. But, like those that came before it, this line of inquiry went nowhere—Sutton had not reviewed the rejected publications. Id. at 233:10–235:11. This lack of preparation left her unable testify about the Department’s decisions. See, e.g., id. at 222:2–5, 233:6–9, 234:21–235:11. Nor could Sutton explain why NCDPS included HRDC on its Master List of Disapproved Publications, despite that being a designated topic. Id. at 154:16–18. And even though NCDPS policy states that publishers should only be on the Master List for a term of twelve months, Sutton could not say why HRDC had been banned from distributing materials for nearly ten years. Id. at 157:22–25. HRDC appealed NCDPS’s decision to reject its publications, but Sutton had reviewed neither the appeals nor the Department’s responses to them. See id. 57:16–25, 30:12–18. This, too, was a designated topic. Sutton’s lack of preparation was not the only roadblock preventing a fruitful deposition. HRDC also contends that NCDPS’s attorney—Shelby Boykin—lodged baseless objections and improperly instructed Sutton not to answer certain questions. See Mem. Supp. Mot. Compel Second Dep. at 6–8, D.E. 48. Most of these objections occurred while HRDC tried to ask Sutton why NCDPS had denied specific HRDC publications. Several times throughout the deposition, counsel for HRDC brought up individual rejected publications, asking Sutton to identify the prohibited material in each document. As discussed above, she could not do so. See, e.g., Dep. Tr. at 234:21–235:11. Eventually, Boykin objected to HRDC’s line of questioning, contending that NCDPS’s reason for rejecting each publication was evident from the rejection letters themselves. Id. at 235:12–20. Elsewhere, however, Boykin 4 Case 5:21-cv-00469-FL Document 64 Filed 04/07/23 Page 4 of 17 lodged a speaking objection to a similar question on the grounds that NCDPS may have forgotten why it prohibited the documents. Id. 222:9–223:2. Boykin’s objections were many, and they occurred more often toward the end of Sutton’s deposition. One example is illustrative: NCDPS prohibited HRDC from sending an Issue from Volume 30 of its Prison Legal News publication to prisoners. In its letter to HRDC justifying the rejection, NCDPS claimed that pages 1 and 28 of the Issue “contained inflammatory articles against prisons[.]” Id. at 231:17. Counsel for HRDC asked Sutton to look at page one of the document and “identify the material . . . that is referenced in the letter to the publisher[.]” Id. at 231:23–24. Sutton claimed she could not. Id. at 231:25. Just after Sutton answered the question, however, Boykin objected to it and instructed Sutton not to answer. Id. at 232:1–2. To justify this objection and instruction, Boykin only offered that the question was beyond the scope of HRDC’s list of deposition topics. 3 Id. at 232:5–6; see also id. at 130:1–7 (instructing Sutton not to answer a different question Boykin believed to be beyond the scope of the deposition notice). HRDC asked Sutton to read deposition topic number two, which specifically asks about NCDPS’s rationale for rejecting each HRDC publication, but Boykin renewed her objection all the same. Id. at 235:8–23. The rationale for rejection—Boykin maintained—lies in the rejection letters themselves. Id. at 235:20–21. Under Boykin’s theory, Sutton did not need to expound upon the letters at all. Id. 235:21–23; 237:21–24 (“[F]or the record, [NCDPS] would renew the objection for all of those publications that you were planning to ask that same line of questioning.”). HRDC’s counsel then changed the subject and suggested that the Center would move to compel fuller testimony. Id. at 237:12–20. It is unclear from the deposition transcript whether Boykin alleged that the question was beyond the scope of the deposition topics to justify her instruction not to answer HRDC’s question, or to assert a separate objection altogether. If the latter is true, Boykin offered no grounds for her instruction not to respond. 3 5 Case 5:21-cv-00469-FL Document 64 Filed 04/07/23 Page 5 of 17 About a month later, HRDC made good on its promise. On January 9, 2023, HRDC asked the court to compel NCDPS to produce an adequately prepared designee, overrule Boykin’s objections and instructions not to answer, and require the Department to pay the fees and costs associated with a second deposition. Mot. Compel Second Dep. at 1. All told, HRDC alleges that Sutton could not testify about 13 of the 22 designated topics, either because she was unprepared or because Boykin instructed her not to answer. See Mem. Supp. Mot. Compel Second Dep. at 4– 6. According to the court’s Local Civil Rules, NCDPS’s response was due on January 23, 2023. See Local Civil Rule 7.1(f)(2). On that date, NCDPS moved to extend the response deadline until January 30, 2023. The court, however, rejected NCDPS’s motion the next day because it failed to indicate whether HRDC consented to the extension of time. See Local R. Civ. P. 6.1(a). NCDPS corrected this deficiency and refiled its motion. Despite the extension requested in its motion, NCDPS did not file a response on January 30, 2023. On February 28, 2023, the court granted the motion for extension of time and gave NCDPS until March 3, 2023, to respond. That deadline, too, came and went without a filing. In late March 2023, as this motion was pending, the North Carolina Department of Adult Corrections replaced NCDPS as a named Defendant. Order Granting Mot. Substitute Party Def., D.E. 63. This substitution was necessary because, at the start of this year, the State of North Carolina established NCDAC and transferred NCDPS’s prison management responsibilities— including the responsibility to review publications sent to prisoners—to that new agency. See Mot. Substitute Party ¶ 7, D.E. 61. NCDAC has also “assume[d] all of [NCDPS’s] legal obligations...related to [this] litigation.” Mot. Substitute Party ¶ 10. 6 Case 5:21-cv-00469-FL Document 64 Filed 04/07/23 Page 6 of 17 II. Discussion The performance of NCDPS’s Rule 30(b)(6) designee fell below the standards required by the Federal Rules. Sutton attended the deposition unprepared to testify about most of the topics marked for discussion, and Boykin’s objections to HRDC’s questions find no support in law. Thus, the court will order NCDPS to appoint a new designee for a second deposition and overrule the Department’s objections. And because the production of an unprepared designee amounts to failure to appear, the court will also impose sanctions. A. Adequacy of Designee’s Preparation to Testify Under the Federal Rules, a party may depose a “public or private corporation, a partnership, an association, a governmental agency, or other entity[.]” Fed. R. Civ. P. 30(b)(6). To do so, the party seeking the deposition must serve the organization with a notice or subpoena that “describe[s] with reasonable particularity the matters for examination.” Id. The organization must then designate someone to testify on its behalf “about information known or reasonably available to the organization” on the listed topics. Id. Designating someone to testify is only the beginning of an organization’s responsibilities. The organization must also prepare its designee “to fully and unevasively answer questions about the designated subject matter.” Wilson Land Corp. v. Smith Barney, Inc., 2001 WL 1745241, at *4 (E.D.N.C. Aug. 20, 2001) (Flanagan, M.J.). If the deposition topics lie beyond the designee’s personal knowledge, then he must make a good-faith effort to learn sufficient information to address them. As part of this process, to “the extent that matters are reasonably available,” the designee must consult “documents, present or past employees, or other sources.” Wilson v. Lakner, 228 F.R.D. 524, 528 (D. Md. 2005). The designee may also have to review “‘prior fact witness deposition testimony as well as documents and deposition exhibits.’” Wilson Land Corp., 2001 WL 1745241, at *5 (quoting United States v. Taylor, 166 F.R.D. 356, 362 (M.D.N.C. 1996)). 7 Case 5:21-cv-00469-FL Document 64 Filed 04/07/23 Page 7 of 17 There is a possibility that—despite the designee’s best efforts—he may not be able to adequately address all questions posed by his interlocutor. In that case, the organization “ha[s] a duty to substitute another person once the deficiency of its Rule 30(b)(6) designation [becomes] apparent during the course of the deposition.” Marker v. Union Fid. Life Ins. Co., 125 F.R.D. 121, 126 (M.D.N.C. 1999). But organizations may not swap documents for a designee—they bear responsibility for identifying and preparing someone who can answer the deposing party’s questions. See Wilson, 228 F.R.D. at 530 (“Corporations must act responsively; they are not entitled to declare themselves mere document-gatherers. They must produce live witnesses who know or who can reasonably find out what happened in given circumstances.”). If an organization fails to produce a qualified individual, the court may order it to identify a new designee who must attend a second Rule 30(b)(6) deposition. See, e.g., id. (citing Marker, 125 F.R.D. at 126). HRDC alleges—and NCDPS does not contest—that Sutton was unprepared to discuss 13 of the 22 topics laid out in the deposition notice. 4 See Mem. Supp. Mot. Compel Second Dep. at 4–6. Sutton repeatedly remarked that she was unaware of the facts underlying HRDC’s questions. See, e.g., Dep. Tr. at 57:16–25, 30:12–18, 222:2–5, 233:6–9, 234:21–235:11. And all she did to prepare for the deposition was discuss the deposition with counsel, exchange some emails, and reread NCDPS’s publication policy. See id. at 14:6–10. She reviewed no other documents. Sutton could not meaningfully discuss the 13 deposition topics HRDC highlights, including: the content of HRDC’s rejected publications; NCDPS’s reasons for rejecting them; the people involved in rejecting publications; NCDPS’s Master List of Disapproved Publications; NCDPS’s answer to HRDC’s complaint; NCDPS’s interrogatory responses; and communications between the two organizations. And when it became apparent that Sutton was not prepared for the HRDC alleges that NCDPS did not address topics 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 13, 18, 20, and 22. See Am. 30(b)(6) Notice at 5–6, D.E. 48-5. 4 8 Case 5:21-cv-00469-FL Document 64 Filed 04/07/23 Page 8 of 17 deposition, the Department did not produce a more knowledgeable deponent. The Federal Rules— and this court—expect more. The court concludes that NCDPS must produce a suitable designee to attend a second Rule 30(b)(6) deposition. B. Appropriateness of Objections The Federal Rules only allow an attorney to instruct her client not to answer deposition questions in narrow circumstances. Under Rule 30, “[a] person may instruct a deponent not to answer only when necessary to preserve a privilege, to enforce a limitation ordered by the court, or to present a motion” to terminate the deposition. Fed. R. Civ. P. 30(c)(2). And while attorneys may lodge objections to deposition questions on the record, these objections must “be stated concisely in a nonargumentative and nonsuggestive manner” and cannot prevent the line of inquiry from continuing. Id. If an attorney believes opposing counsel is conducting a deposition in bad faith, he must move to end the deposition and bring his concerns before the court. See, e.g., Ralston Purina Co. v. McFarland, 550 F.2d 967, 973–74 (4th Cir. 1977). Turning first to Boykin’s instructions not to answer, the court finds that they lack merit. Boykin advised Sutton not to answer multiple questions because she believed that HRDC’s inquiries extended beyond the scope of its deposition topics. See Dep. Tr. at 130:1–7, 232:5–6. Even if Boykin was correct (and she was not), the Federal Rules do not allow her to instruct a client not to answer a question because it asks for information outside the topics noticed for deposition. 5 See Fed. R. Civ. P. 30(c)(2). Thus, Boykin’s instructions not to answer violated the Rules. If a designee answers questions that fall outside the scope of the topics included with the Rule 30(b)(6) notice, those answers do not bind the organization. See Mitnor Corp. v. Club Condos., 339 F.R.D. 319, 321 (N.D. Fla. 2021);Green v. Wing Enters., Inc., No. 1:14-CV-01913, 2015 WL 506194, at *8 (D. Md. Feb. 5, 2015); EEOC v. Freeman, 288 F.R.D. 92, 99-100 (D. Md. 2012). 5 9 Case 5:21-cv-00469-FL Document 64 Filed 04/07/23 Page 9 of 17 Aside from her instructions not to answer, Boykin’s objections fail. Several times throughout the deposition, Boykin objected to questions aimed at understanding the precise language in HRDC’s publications that barred them from distribution. See, e.g., Dep. Tr. at 222:9– 223:2, 232:19–23; 235:12–20, 236:19–20. Boykin offered several different grounds for objection: At one point, she claimed that the questions were irrelevant. Id. at 222:14–223:2. But NCDPS’s deposition notice expressly lists “the rationale for NCDPS’[s] decision to reject any HRDC publication” as a topic of discussion—asking Sutton which passages in the publication merited rejection falls within this area of inquiry. See Am. 30(b)(6) Notice at 5, D.E. 48–5. Elsewhere, Boykin claimed that the line of questioning was improper because NCDPS’s rationale for prohibiting each publication was evident from the rejection letters the Department sent HRDC. Dep. Tr. at 232:19–23, 235:12–20. But organizations sitting for a deposition “are not entitled to declare themselves mere document-gatherers. They must produce live witnesses who know or who can reasonably find out what happened in given circumstances.” Wilson, 228 F.R.D. at 530. NCDPS’s rejection letters merely flagged page numbers containing prohibited material; they did not explain the language that merited rejection. HRDC was well within its rights to ask Sutton for more specific information. 6 Boykin lodged several other objections throughout the deposition, but they are just as unpersuasive. See, e.g., Dep. Tr. at 186:2–13, 224:12–18, 236:25–237:9. Throughout the deposition, HRDC’s questions centered around the topics listed in the deposition notice. Thus, the court overrules all Boykin’s objections. This objection also conflicts with one of Boykin’s earlier statements defending her relevance objection, when she suggested that NCDPS may have forgotten why it rejected the publications. See Dep. Tr. at 222:14–21. 6 10 Case 5:21-cv-00469-FL Document 64 Filed 04/07/23 Page 10 of 17 C. Imposition of Sanctions HRDC asks the court to sanction NCDPS for its failure to adequately prepare its designee. It claims that Sutton’s lack of preparation amounts to a failure to appear at the deposition. Thus, it seeks to recover, under Rule 37(d)(3), the fees and costs it will incur intaking NCDPS’s deposition a second time as well as the fees and costs related to pursuing this motion. Federal Rule 37 requires the court to impose sanctions against a party that fails to attend its own deposition, the party’s attorney, or both. Fed. R. Civ. P. 37(d)(3). The offending party must pay for the other side’s “reasonable expenses, including attorney’s fees, caused by the failure, unless the failure was substantially justified or other circumstances make an award of expenses unjust.” Id. Of course, Sutton appeared at her deposition. But merely having a designee appear at a Rule 30(b)(6) deposition is not enough to satisfy the Rule’s requirements—the designee must be prepared to testify on the noticed topics. So courts routinely hold that an organization’s failure to appoint a qualified, prepared individual to sit for a Rule 30(b)(6) deposition amounts to a failure to attend. See, e.g., Taylor, 166 F.R.D. at 363; Resol. Tr. Corp. v. S. Union Co., 985 F.2d 196, 197 (4th Cir. 1993) (“If [the designee] is not knowledgeable about relevant facts, and the [organization] has failed to designate an available, knowledgeable, and readily identifiable witness, then the appearance is, for all practical purposes, no appearance at all.”). As discussed above, NCDPS and its counsel failed to prepare Sutton for her deposition. Her lack of preparedness nullified the deposition’s value and amounted to a failure to appear. This failure to appear caused HRDC to pursue this motion and requires the Center to take NCDPS’s deposition a second time to obtain the discovery it needs to pursue its claims. Thus, Rule 37(d)(3) 11 Case 5:21-cv-00469-FL Document 64 Filed 04/07/23 Page 11 of 17 requires entitles HRDC to recover the costs and expenses it incurred in connection with this motion and NCDPS’s second deposition. 7 NCDPS could still avoid sanctions if it showed that the failure to prepare Sutton “was substantially justified or other circumstances make an award of expenses unjust.” Id. But since its counsel did not respond to HRDC’s motion—despite having nearly 8 weeks to do so—it has waived any argument of the sort. See Ctr. for Biological Diversity v. Raimondo, 610 F. Supp. 3d 252, 277 (D.D.C. 2022) (“A court can treat ‘specific arguments as conceded’ when a ‘party fails to respond to arguments in opposition papers.’”); New Wellington Fin. Corp. v. Flagship Resort Dev. Corp., 416 F.3d 290, 295 (4th Cir. 2005) (explaining that courts “can ignore arguments forfeited because they are not presented consistent with the court’s time limits”); Day v. D.C. Dep’t of Consumer & Regul. Affs., 191 F. Supp. 2d 154, 159 (D.D.C. 2002) (“If a party fails to counter an argument that the opposing party makes in a motion, the court may treat that argument as conceded.”). The North Carolina Department of Justice’s failure to respond on its client’s behalf, while unfortunate, is unsurprising. This is the latest of many occasions when attorneys from NCDOJ have been unwilling or unable to meet requirements placed on them by this court and the Federal Rules. See, e.g., Show Cause Order, Mayo v. Rocky Mount Police Dep’t, No. 5:22-CV-00289-MRN (E.D.N.C. Feb. 8, 2023), D.E. 48 (setting show cause hearing for “the direct, intentional violation” of a court order and the local rules); Hale v. Wilson Cnty., No. 5:19-CV-00550-BO, Although in some cases, the Eleventh Amendment precludes an award of monetary damages against a State, that is not the case when it comes to discovery sanctions. See Missouri v. Jenkins ex rel. Agyei, 491 U.S. 274, 284 (1989) (“[T]he Eleventh Amendment has no application to an award of attorney's fees, ancillary to a grant of prospective relief, against a State.”); Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678, 689–93 (1978) (rejecting argument that the Eleventh Amendment prohibits imposing monetary sanctions against state agencies for violating a court order); Sisney v. Kaemingk, 15 F.4th 1181, 1200 (8th Cir. 2021) (“The Eleventh Amendment does not bar a federal court from enforcing its orders against a state entity, including, if necessary, by sanctions.”) Lee v. Walters, 172 F.R.D. 421, 434 (D. Or. 1997) (finding that the Eleventh Amendment does not prohibit imposing monetary sanctions against the State or a state-employed lawyer for discovery violations). 7 12 Case 5:21-cv-00469-FL Document 64 Filed 04/07/23 Page 12 of 17 2022 WL 4084411, at *2 (E.D.N.C. Sept. 6, 2022) (sanctioning counsel from NCDOJ for violating Rule 45(d)(1) by failing to take reasonable steps to avoid unduly burdening a subpoena recipient); Show Cause Order at 1, Griffin v. Daves, No. 5:19-CT-03040-M (E.D.N.C. Nov. 9, 2021), D.E. 105 (requiring defendants to show cause why they failed to comply with an order requiring them to make certain filings); Show Cause Order, Ollis v. Hawkins, No. 5:18-CT-03276-D (E.D.N.C. Aug. 20, 2021), D.E. 47 (setting show cause hearing for violating a court order); Show Cause Order, Dean v. Jones, No. 5:16-CT-03109-FL (E.D.N.C. Mar. 17, 2021), D.E. 103 (setting show cause hearing for violating a court order); Certification of Contempt, Johnson v. N.C. Dep’t of Justice, No. 5:16-CV-00679 (E.D.N.C. Feb. 13, 2019), D.E. 51 (initiating contempt proceedings because the Senior Deputy Attorney General failed to comply with a court order). North Carolina’s other federal courts have had similar issues. One District Judge commented that an NCDOJ attorney has a “history in this and other cases . . .[of] fail[ing] to adhere to the Court’s deadlines and. . .be[ing] generally nonresponsive[.]” Order at 4, Griffin v. Hooks, No. 3:19-CV-00135-MR (W.D.N.C. Oct. 27, 2021), D.E. 149. There are many more examples. See, e.g., Bolen v. Smith, No. 3:19-CV-00709-MR, 2023 WL 373885, at *3 (W.D.N.C. Jan. 24, 2023) (rejecting counsel’s claim that he was unaware certain discovery had been served and explaining that “this level of disingenuousness with the Court is not taken lightly”); Torres v. Ishee, No. 1:21-CV-00068-MR, 2023 WL 213918, at *2 (W.D.N.C. Jan. 17, 2023) (granting motion to compel based on failure to respond in timely manner to discovery); Parks v. Poole, No. 1:20-CV-00898-WO-JLW, 2022 WL 4622264, at *1 n.1 (M.D.N.C. Sept. 30, 2022) (noting that a “motion and accompanying memorandum are full of typographical errors, formatting errors from what appears to be cutting and pasting, and formatting errors in violation of the rules of this court”); Order at 2, McClellan v. Schetter, No. 1:20-CV- 13 Case 5:21-cv-00469-FL Document 64 Filed 04/07/23 Page 13 of 17 00189-MR (W.D.N.C. Dec. 8, 2021), D.E. 48 (noting “defense counsel’s history with this Court in failing to abide the deadlines of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and the Court and to generally manage his cases”); Show Cause Order at 3, Griffin v. Hooks, No. 3:19-CV-00135-MR (W.D.N.C. July 28, 2021), D.E. 121 (concluding that “defense counsel makes no consistent effort to manage this case properly and professionally himself” and observing that other counsel would better serve defendant’s interests); Order at 1, McNeill v. Herring, No. 3:18-CV-00189-GCM (W.D.N.C. Oct. 13, 2021), D.E. 63 (finding that counsel for defendants failed to comply with court-ordered deadlines to file trial submissions); Order, Mem. & Recommendation at 2, Musgrove v. Moore, No. 1:19-CV-00164-CCE-JLW (M.D.N.C. Dec. 10, 2020), D.E. 26 (noting previous entry of default against defendants when they filed no answer or responsive pleading to a served complaint); Show Cause Order at 4–5, Griffin v. Hollar, No. 5:19-CV-00049-MR (W.D.N.C. Dec. 9, 2020), D.E. 66 (requiring defense counsel to show cause why the court should not enter default against defendants for failure to timely answer or otherwise respond to the complaint). To explain these deficiencies, attorneys from the North Carolina Department of Justice’s Public Safety Section regularly invoke their workload. But attorneys who appear in this court have a professional responsibility to not take on more work than they can manage. N.C. R. Prof. Conduct 1.3, Comment 2 (“A lawyer’s work load must be controlled so that each matter can be handled competently.”); see Strike 3 Holdings, LLC v. Doe , No. 1:18-CV-01075-MCE-CKD, 2019 WL 935389, at *4 (E.D. Cal. Feb. 26, 2019) (explaining that an attorney “has a professional responsibility to refrain from acting as counsel in more cases than he can handle at one time”); Deitrick v. Costa, No. 4:06-CV-1556, 2014 WL 12884515, at *11 (M.D. Pa. Dec. 11, 2014) (“[A]n attorney who knowingly takes on an unmanageable caseload and thereby fails to meet deadlines acts willfully.”) (citation omitted); United States v. Bush, 797 F.2d 536, 538 (7th Cir. 1986) (per 14 Case 5:21-cv-00469-FL Document 64 Filed 04/07/23 Page 14 of 17 curiam) (“[A]n attorney is responsible for managing his office so that he can comply with [the] court’s orders and rules.”). So the Department’s busyness does not excuse its repeated failures to meet its professional obligations. Other explanations are even less persuasive. See, e.g., Feb. 14, 2023 Show Cause Hr. Tr. at 4:18–24, Mayo v. Rocky Mount Police Dep’t, No. 5:22-CV-00289-M-RN (E.D.N.C. Mar. 3, 2023), D.E. 55 (explaining that an attorney did not comply with a five-page court order because she did not read all of it); Response to Certification of Contempt ¶ 11, Johnson v. N.C. Dep’t of Justice, 5:16-CV-00679-FL (E.D.N.C. Feb. 14, 2019), D.E. 52 (attempting to justify failure to comply with a court order by noting the possibility that the attorney “simply overlooked the email” containing the order because “on a daily basis [he] receive[s] a copious number of email messages”). The court has addressed these issues, in person, with both the head of the Public Safety Section and the North Carolina Department of Justice’s Criminal Bureau Chief. Feb. 14, 2023 Show Cause Hr. Tr., Mayo v. Rocky Mount Police Dep’t, No. 5:22-CV-00289-M-RN (E.D.N.C. Mar. 3, 2023), D.E. 55; Sept. 20, 2021 Show Cause Hr. Tr., Ollis v. Hawkins, 5:18-CT-03276-D (E.D.N.C. Sept. 29, 2021), D.E. 56. But the problems persist. The court is left with no choice but to impose sanctions. Thus, in light of NCDPS’s failure to adequately prepare its designee and its counsel’s failure to show that sanctions are inappropriate, the court will grant HRDC the relief it seeks. HRDC is entitled to recover the fees and costs related to this motion and the second Rule 30(b)(6) deposition. 15 Case 5:21-cv-00469-FL Document 64 Filed 04/07/23 Page 15 of 17 III. Conclusion For the reasons discussed above, the court grants HRDC’s Motion to Compel Second Deposition and for Sanctions (D.E. 47) in full and orders the following: • NCDPS (or NCDAC, as its successor in interest) must appoint—and prepare—a new designee to sit for a second Rule 30(b)(6) deposition on topics 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 13, 18, 20, and 22. See Am. 30(b)(6) Notice at 5–6. • NCDPS’s objections to HRDC’s questions are overruled. At the second deposition, NCDPS (or NCDAC, as its successor in interest) must ensure that its designee is prepared to discuss the 13 outstanding topics—including the precise language in HRDC’s publications that caused NCDPS to reject them—in full. • NCDAC is responsible for: o HRDC’s reasonable attorney fees incurred in preparing for and taking the second Rule 30(b)(6) deposition; o Any court reporter fee for the second Rule 30(b)(6) deposition; o Any videographer fee for the second Rule 30(b)(6) deposition; o The cost of producing the transcript from the second Rule 30(b)(6) deposition; and o The costs and reasonable attorney fees associated with HRDC’s travel to the second Rule 30(b)(6) deposition. • NCDAC is also responsible for the costs and reasonable attorney fees associated with HRDC’s Motion to Compel Second Deposition and for Sanctions and the accompanying Memorandum of Law. 16 Case 5:21-cv-00469-FL Document 64 Filed 04/07/23 Page 16 of 17 • The Clerk of Court must serve a copy of this order on the Honorable Joshua H. Stein, the Attorney General of the State of North Carolina. The court will issue a separate order modifying the case management order and setting a schedule for the calculation and payment of the fees owed by NCDAC. NCDPS, NCDAC, and their counsel are cautioned that failure to comply with this order may result in the imposition of further sanctions, including entry of default judgment against Defendants. Dated: April 7, 2023 Dated: £'~7- ~?Z- ROBERT T. NUMBERS, II ______________________________________ UNITEDT.STATES MAGISTRATE JUDGE Robert Numbers, II United States Magistrate Judge 17 Case 5:21-cv-00469-FL Document 64 Filed 04/07/23 Page 17 of 17