Prison Legal News v. Prison Health Services, Vermont, Complaint, Public Records, 2010

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

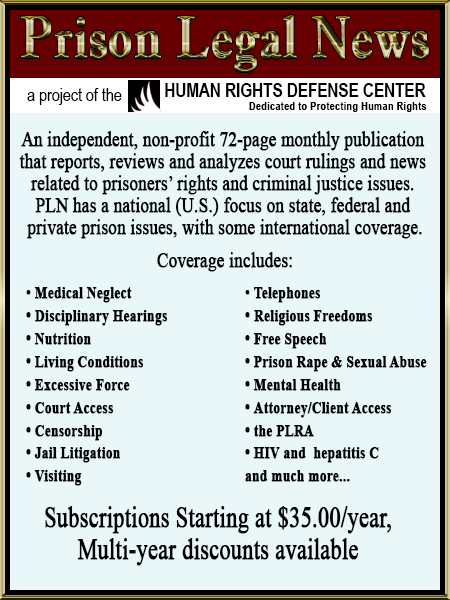

STATE OF VERMONT SUPERIOR COURT WASHINGTON UNIT CIVIL DIVISION Docket No. PRISON LEGAL NEWS Plaintiff v. PRISON HEALTH SERVICES, INC. Defendant Complaint and Petition for Declaratory Judgment and Permanent Injunctive Relief, with Supporting Memorandum of Law COMES NOW Plaintiff, by and through counsel, David Sleigh, and respectfully requests the above-captioned Court to redress his grievance as follows: Nature of the Action 1. Defendant Prison Health Services (PHS), a private corporation that served until 2009 as the functional equivalent of a state agency, has refused to disclose certain records, as requested by Plaintiff and to which it is entitled under the Vermont Public Records Act. 1 V.S.A.§316-320; 2. The harm to Plaintiff as a result of Defendant’s refusal to disclose requested public records under the Act is sufficiently real and imminent to warrant the issuance of declaratory judgment and permanent injunctive relief; 3. Plaintiff does hereby bring this action and asks the Court to declare, pursuant to 12 V.S.A. §4711 and V. R. Civ. P. 57 and 65, that Defendant is a public body subject to the disclosure requirements of Vermont’s Public Records Act, that the documents requested are within the scope of its disclosure obligations and not subject to any statutory exemptions, and further to enjoin Defendant, pursuant to 1 V.S.A. § 319(a) (“Enforcement”) from continuing to withhold the documents which Plaintiff has requested and to which it is entitled; 4. Plaintiff further demands that Defendant pay reasonable attorney’s fees and litigation costs incurred attendant to prosecuting the instant action. 1 V.S.A. §319(d). Parties 5. Plaintiff Prison Legal News (PLN)—a project of the Human Rights Defense Center--is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization responsible for the publication of a serious legal and political journal that reports on news and litigation involving detention facilities. PLN has successfully litigated public records cases across the nation, on behalf of the public interest. Neither Plaintiff nor its parent organization is currently a party to any pending litigation involving Defendant PHS; 6. Defendant is a private corporation with headquarters in Brentwood, Tennessee and was, at all times pertinent to Plaintiff’s request for public records, the functional equivalent of a public agency due to its contracted relationship with the Vermont Department of Corrections (DOC); -2- Facts 7. Defendant PHS provides health care services to inmates at numerous state corrections facilities and departments across the nation; 8. From 2005 until 2009, the Vermont DOC contracted with PHS to deliver health care and medical services to inmates at its Vermont facilities; 9. Defendant currently retains the law firm of Dinse, Knapp & McAndrew, P.C. of Burlington, Vermont to represent some or all of its legal interests in the state of Vermont; 10. In August, 2010, Plaintiff submitted a written request to Defendant for documentation of all legal claims and settlements made by PHS in connection with services provided to Vermont inmates pursuant to its contractual relationship with the Vermont DOC and records of all disbursements of fees incurred in the litigation or settlement of such claims, including dollar amounts paid to the firm Dinse, Knapp & McAndrew, P.C. for legal services rendered. Plaintiff requested these records specifically under color of the Vermont Public Records law. See Ex A. 11. Subsequently, Defendant refused—in writing—to disclose these documents, arguing that Defendant is not a public agency within the meaning of the statute, and further arguing that even if it were found to be a public agency, the records Plaintiff has requested are exempt under various provisions of 1 V.S.A. §317. See Ex. B -3- Supporting Memorandum of Law Any dispute as to the applicability of Vermont’s Public Records Act must inevitably turn on two basic questions of law. First, does the agency, corporation or organization in question meet the criteria of a public agency subject to the public records statute? Second, if the organization is indeed subject to the public records laws, must the records requested be provided under those laws, or do they fall under any of the exemptions enumerated in the statute? Prison Health Services, by virtue of its contractual relationship with the Vermont Department of Corrections, was a public agency subject to Vermont’s public records statute. The Vermont Public Records Act defines “public agency” as “any agency, board, department, commission, committee, branch, instrumentality, or authority of the state or any agency, board, committee, department, branch, instrumentality, commission, or authority of any political subdivision of the state.” 1 V.S.A.§317(a) Under this definition, the Vermont DOC is certainly a public agency. DOC is a state agency charged with the constitutional mandate to provide medical services to inmates. Like many state departments of corrections, however, the Vermont DOC has a longstanding practice of “outsourcing” the provision of inmate medical services to private corporations. In this case, DOC contracted with Defendant PHS for that purpose, hiring the company specifically to carry out functions under the purview of state -4- government. Because PHS carried out those functions exclusively while contracted by the Vermont DOC, it became an “instrumentality” and the functional equivalent of a public agency. It was therefore and remains—for the pertinent incidents and time frame-subject to the same public record disclosure laws which govern the Vermont DOC. In February 2005, the Vermont (DOC) entered into a written contract with PHS, a private, for profit-company. That contract spelled out the basic terms by which PHS was to “facilitate and enable the delivery of health care services to the Vermont DOC inmates in Vermont.” Among its many other provisions, the document stated that the contractor shall: 1) Meet the health care needs of inmates in accordance with applicable state and federal laws; 2) Provide services as set out in the contract in compliance with the applicable terms of the Settlement Agreement in Goldsmith et al v. Dean, et al, dated April 11, 1996; 3) Participate in applicable state-sponsored quality improvement projects as directed by the DOC; 4) Incorporate local community care providers in its system of care; 5) Coordinate activities with the Vermont DOC Health Services Director or designee. In the event of a dispute between the Contractor (PHS) and the State on a clinically-related matter, the DOC Health Services Director will have final decision-making authority. The contract’s terms further mandated that PHS would: -5- A) make all financial records available for audit by authorized representatives of the state and federal government; B) as part of the “Final Adopted Rule for Access to Information,” make information defined as public by 1 V.S.A. §317 or other applicable statute available to the public; C) as part of a series of “Customary State Provisions,” agree to become a voter registration agency as defined by 17 V.S.A. § 2103 and to comply with State and Federal law pertaining to such agencies; D) stipulate to an agreement that PHS employees would be covered by the State’s collective bargaining agreement with the Vermont State Employees’ Association. It is clear from the scope of the contract and its numerous provisions, large and small, that PHS operated within the parameters of a wide array of Vermont laws, regulations and employment agreements, and exercised relatively little autonomy. In other words, this was a contractual relationship with the state agency exercising considerable, if not complete, power over the private contractor. Perhaps most important, the contract itself explicitly defined PHS as subject to disclosure of all records, including all financial records. According to the “Customary State Provisions,” PHS must make available all financial records to Vermont state auditors. This demonstrates clear intent that PHS records would be available to taxpayers and citizens. That intent is articulated even more specifically under the “Final Adopted Rule for Access” portion of the contract, which states “information defined as -6- public by 1 V.S.A. §317…is available to the public.” The contract itself, then, incorporated and adopted Vermont’s Public Records Act. Finally, the PHS-DOC contract contained indemnification language, as might be expected. This indemnification clause held that “the contractor shall indemnify, defend and hold harmless the state and its officers from liabilities any claims, suits, judgments and damages which arise as a result of the contractor’s acts or omissions in the performance of services under this contract.” In sum, PHS agreed to be responsible for any liability it generated in fulfillment of the contract. This means that the Vermont DOC, as “part of the bargain,” contracted and paid for any legal defense fees that might become necessary as PHS went about the business of providing medical services to inmates. Exactly how a private company becomes subject to public disclosure laws is a matter of first impression in Vermont. But since the early 1980s and the Reagan era, when the wave of “outsourcing” or privatization of government services first began in earnest, thirty four states have rendered decisions as to when a private company must disclose its records under public records statutes. Recognizing the special problems that arise with privatization of government services and taxpayer accountability, a majority of states have litigated and ruled on the question of private companies’ obligations to disclose. A review of those decisions across jurisdictions shows a variety of approaches to the question of private-company-as-public-agency. Those approaches range from flexible approaches generally more favorable to access, to those that permit access using more restrictive criteria. There’s a clear trend: over the decades, states have moved -7- decisively in the direction of construing the definition of a public agency very liberally, using flexible approaches rather than restrictive ones. Eight states—Connecticut, Florida, Maryland, North Carolina, Oregon, Kansas, Tennessee and Ohio now utilize a totality of factors, or “functional equivalency” approach. In this model, one factor alone is not sufficient to grant access, but neither will the absence of one suffice to deny it. Those Courts have based their rulings on a series of criteria, including the interrelationship between the government and private entity, the public purpose of the private entity, the degree of government control over the public entity, creation of the entity by statute, and the entity’s immunity from tort liability. The Connecticut Supreme Court pioneered and formalized the model in 1991 and employs four specific criteria: 1) Whether the entity performs a governmental function; 2) The level of government funding; 3) The extent of government involvement or regulation; and 4) Whether the entity was a creation of the government. See Connecticut Humane Society & Freedom of Information Com’n, 218 Conn. 757 (1991). In the 19 years since the Connecticut Supreme Court’s ruling, five other states— --adopted the four-part functional equivalency test, concluding that the test is a “superior method” for determining whether or not public records laws apply to private companies. 1 1 News and Sun-Sentinel Co. v. Schwab, Twitty & Hanser Architectural Group, Inc., 596 So. Wd1029 (Fla. 1992); A.S. Abell Publishing Co. v. Mezzanote, 297 Md. 26 (1983); News and Observer Publishing Co. v. Wake County Hosp. Systems, Inc., 284 S.E.2d 542 (N.C. Ct. App. 1981). Marks v. McKenzie High School Fact-Finding Team, 878 P.2d 417 (Or.1994); 27 Kan. Op. Att’y Gen. 47 (1993) WL 467822 at 1; Memphis Publishing Co. et al v. Cherokee Children & Family Services, Inc., et al, -8- Other jurisdictions have developed models which select parts of the functional equivalency test, or various hybrids thereof. Eleven other states have opted to rely exclusively on the extent to which the company serves a public function. Georgia, New York, California, Louisiana, Missouri, New Jersey, Utah, Kentucky, Delaware, Iowa and New Hampshire use the “public function” test or some form of a hybrid between the public function approach and criteria based upon the level of public funding.2 Yet another approach involves evaluating the nature of the material requested under public disclosure statutes. Courts in the jurisdictions of Maine, Minnesota, Washington and Wisconsin have relied on this approach; one where the Court considers the nature of the records themselves, usually asking the question whether the records concern matters related to a government function, despite being in the possession of the private company.3 Another group of jurisdictions has chosen to focus exclusively on the level of funding which the private entity receives in order to determine whether it is subject to public disclosure laws. For example, the Michigan Court of Appeals ruled that a private, non-profit foster care agency was exempt from to the Michigan Freedom of Information 87 S.W. 3d 67 (Tenn. 2002); The State ex rel. Oriana House, Inc., v. Montgomery, Aud., 110 Ohio St. 3d 456 (2006) 2 Hackworth v. Board of Education, 447 S. E. 2d 78 (Ga. Ct. App. 1994); Encore College Bookstores, Inc. v. Auxiliary Service Corp., 663 N.E. 2d 302 (N.Y. 1995); San Gabriel Tribune v. Superior Court, 192 Cal. Rptr. 415 (Cal. Ct. App. 1983); State ex rel. Guste v. Nicholls College Foundation, 564 So. 2d 682 (La. 1990); Cohen v. Poelker, 520 S. W. 2d 50 (Mo. 1975); Fair Share Housing Center, Inc. v. New Jersey State League of Municipalities, 413 N.J. Super. 423 (2010); Barnard v. Utah State Bar, 804 P.2d 526 (Utah 1991); Kentucky Central Life Insurance Co. v. Park Broadcasting of Kentucky, Inc., 913 S.W. 2d 330 (Ky. Ct. App. 1996); Delaware Solid Waste Authority v. News-Journal Co., 480 A. 2d 628 (Del.1984); Mark Gannon and Arlene Nichols v. Board of Regents, State of Iowa, 692 N.W.2d 31 (2005); and Voelbel v. Bridgewater, 667 A.2d 1028 (N.H. 1995). 3 See International Brotherhood of Elec. Workers Local 68 v. Denver Metro. Major League Baseball Stadium District, 880 P.2d 160 (Colo. Ct. App. 1994); Bangor Publishing Co. v. University of Maine System, 224 Media L. Rep. (BNA) 1792 (Me. Super. Ct. 1995); Pathmanathan v. St. Cloud University, 461 N.W. 2d 726 (Minn. Ct. App. 1990); Becky v. Butte-Silver Bow School District No 1., 906 P.2d 193 (Mont. 1995); Laborers’ International Union No. 374 v. City of Aberdeen, 642 P.2d 418 (Wash. Ct. App. 1982); and Journal/Sentinel, Inc. v. School Bd. of the School District, 521 N.W. 165 (Wisc. Ct. App. 1994). -9- Act because it received less than 50% of its funding from state sources. See Kubick v. Child and Family Services, 429 N.W. 2d 881 (Mich. Ct. App. 1988) Other states which have adopted an exclusive “public funding” approach include Arkansas, North Dakota, Indiana, South Carolina and Texas.4 Two other state jurisdictions, Pennsylvania and West Virginia, require a showing that the private entity performs a function established by statute or constitutional mandate, or vital to the continued existence of the state.5 This criteria bears some similarity, of course, to the “public function” approach, but formalizes the criteria to a greater degree. The fourth and final approach is that of Illinois, which limits public disclosure of private company records exclusively to cases in which the private entity is effectively controlled by a public agency. See Hopf v . Topcorp, Inc. 628 N.E.2d 311 (Ill. App. Ct. 1993). In that instance, the Court decided that because the city was unable to control the decision-making process of the private companies in question (even with board representation and 50% public funding), the corporations were not under the direct public control that the statute required in order to make them subject to public disclosure laws. This list demonstrates convincingly that under the majority of state statutes and common law, PHS would be subject to Vermont’s public disclosure law. By considering each basic criteria used by sister jurisdictions and comparing them to the terms of the 4 Sebastian County Chapter of the American Red Cross v. Weatherford, 846 S.W. 2d 641 (Ark. 1993); Adams County Record v. Greater No. Dakota Ass’n, 529 N.W. 2d 830 (N.D. 1995); Indianapolis Convention & Visitors’ Association v. Indianapolis Newspapers, Inc., 577 N.E. 2d 208 (Ind. 1991);; Weston v. Carolina Research& Development Foundation, 401 S.E. 2d 161 (S.C. 1991); Blankenship v. Brazos Higher Education Authority, Inc. 975 S. W.2d 353 (Tex App. 1998) 5 See Community College v. Brown, 674 A.2d 670 (Pa. 1996) and 4-H Road Community Association v. West Virginia University Foundation, Inc., 388 S.E. 2d 308 (W. Va. 1989) - 10 - PHS-Vermont DOC contractual relationship, it becomes evident that PHS is the “functional equivalent” of a state agency, therefore obligated to disclose its records. Does the entity perform a government function? The answer, of course, is a decisive yes. Medical care to inmates is constitutionally mandated by the 8th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. See Estelle v. Gamble, 429 U.S. 97 (1976). Furthermore, the contract between PHS and DOC binds PHS to the terms of a Settlement Agreement stemming from a constitutional challenge to the Vermont DOC’s medical care practices; Level of government funding. The level of government funding for PHS services in Vermont is total. While PHS provides services across the country to various other state departments of corrections, for the purposes of their activities and obligations on behalf of their target population in Vermont, funding comes exclusively from the Vermont DOC, and hence, the taxpayers; Extent of government regulation, or public control. The PHS contract spells out numerous ways that the State of Vermont oversaw, regulated and was otherwise involved in PHS’ delivery of services to inmates. The Contractor was bound to provide services in accordance with Vermont law, comply with settlement agreements stemming from a federal constitutional challenge to Vermont prison conditions, participate in statesponsored quality control program, utilize local community health care providers, defer to the Vermont DOC Health Services Director in the event of disputes over clinical matters, cover its employees under the VSEA collective bargaining agreement, and numerous other requirements. Finally, the contract mandated that PHS’ records— including financial records—would be subject to inspection by state auditors and made available under the Vermont Public Records Act. - 11 - Whether the entity was a creation of the government. Of course, PHS was not technically created by the State of Vermont. However, it is important to recognize that construed even somewhat generously, the Vermont DOC, in a sense, “created” PHS by inviting it to bid and offering it the exclusive contract for the provision of inmate medical services. The particular records Plaintiff has requested are not exempt from Vermont’s public records statute due to privilege or any other reason and must therefore be disclosed. Vermont’s public records law provides for numerous exemptions. But the records of settlements and amounts of fees incurred during litigation and settlement of claims— including a public agency’s payments to legal counsel--do not fall within any of them. There are two clauses in Vermont’s public records law which might exempt certain records for privilege. See 1 V.S.A.§317(c)(3) and (4). The first states that a public record will be exempt if it “would cause the custodian to violate duly adopted standards of ethics or conduct for any profession regulated by the state.” The second provides for exemption if it “would cause the custodian to violate any statutory or common law privilege other than the common law deliberative process privilege as it applies to the general assembly and the executive branch agencies of the state of Vermont.” Clearly, settlement agreements and dollar amounts incurred in the defense against tort or civil rights claims are not the same as the privilege associated with a public agency’s “deliberative process.” Plaintiff does not request any internal memoranda or records/minutes of DOC’s or PHS’ decision-making process on substantive matters of policy and procedure; it simply wants to learn the precise terms of settlement agreements - 12 - and fees incurred in the course of litigating such settlements, including payments to legal counsel. Executive or deliberative privilege does not apply and therefore does not exempt PHS from its obligations to disclose under the law. As for attorney-client privilege, Defendant might reasonably invoke such a privilege if Plaintiff had requested records of attorney work product or records of substantive conversations or communications involving legal advice or litigation strategy. But once again, sister jurisdictions have ruled decisively that while attorney-client privilege can protect some records of a public body from disclosure, that privilege certainly does not constitute a sweeping or “blanket” exemption. In Defendant’s own home state of Tennessee, for example, the Court of Appeals has ruled that a private provider of correctional services—CCA--met the definition of a public agency due to its unique task of carrying out a state government function. (In that case, Plaintiffs had requested invoices and billing statements for settlements and other costs of litigation and the Court ruled that those documents were indeed subject to disclosure under Tennessee public records statutes.) See Friedmann v. Corrections Corporations of America 2009 WL 3131610 (Tenn.Ct.App.)6 Furthermore, the Connecticut Supreme Court has twice ruled that invoices for municipal legal counsel are not exempt under attorney-client privilege, and must therefore be disclosed under the state’s freedom of information laws. In Maxwell, Controller of the Town of Windham et al v. Freedom of Information Commission 260 Conn. 143, 794 A.2d 535 (2002), the Court drew an important distinction between billing records and other records involving legal advice: “At their core, both the common-law 66 Note that the Plaintiff in Friedmann v. Corrections Corporations of America was PLN’s Associate Editor, Alex Friedmann. - 13 - and statutory privileges protect those communications between a public official or employee and an attorney that are confidential, made in the course of the professional relationship that exists between the attorney and his or her public agency client, and relate to legal advice sought by the agency from the attorney.” City of New Haven et al v. Freedom of Information Commission 4 Conn. App. 216, 493 A.2d 283, (1985), the Supreme Court found that a trial court had—after an in camera review of the documents-properly declared invoices and billing statements were not protected by the client privilege exemption. Finally, the New York State Supreme Court considered at length whether fee statements and invoices for county government’s legal services fell under the exemption for attorney-client work product privilege. In preparing the groundwork for an in camera review of the documents, the Court stated “Indeed, ‘[t]he exemption should be limited to those materials which are uniquely the product of a lawyer's learning and professional skills, such as materials which reflect his legal research, analysis, conclusions, legal theory or strategy.’” Orange County Publications v County of Orange, New York 168 Misc.2d 346, 637 N.Y.S.2d 596 (1995). The same Court went on to emphasize: “Respondent's denial of the FOIL request cannot be upheld unless the descriptive material is uniquely the product of the professional skills of respondent's outside counsel. The preparation and submission of a bill for fees due and owing, not at all dependent on legal expertise, education or training, cannot be “attribute[d] ... to the unique skills of an attorney” (quoting Brandman v. Cross & Brown Co., 125 Misc.2d 185, 188, 479 N.Y.S.2d 435 [Sup.Ct. Kings Co.1984] ). - 14 - Therefore, the attorney work product privilege does not serve as an absolute bar to disclosure of the descriptive material.” In short, a public agency’s records of settlement amounts or litigation costs in connection with tort or civil rights actions are subject to disclosure under the law, with no exemption for privilege, attorney-client or otherwise. If Defendant has concerns about collateral privileged matter that may appear adjacent to any of the material requested, the Court may order in camera review of documents. Many courts, both in Vermont and sister jurisdictions, have addressed the issue of privilege exemptions to public records laws by ordering such a review. See Kade v. Smith, 180 Vt 554 (2006) and Killington, Ltd v. Lash, 153 Vt. 628 (1990). The Vermont Public Records Act itself explicitly notes that the Court “may examine the contents of such agency records in camera to determine whether such records or any part thereof shall be withheld under any of the exemptions set forth in section 317 of this title, and the burden is on the agency to sustain its action.” 1 V.S.A. § 319(a) This Court can choose to conduct such an in camera review in order to determine whether billing statements or invoices fall under the Act’s privilege exemptions. However, to save the Court the time and expense of such a proceeding, Plaintiff suggests a simpler solution: Defendant may, prior to producing the documents, redact any substantive information contained therein, leaving simply the settlement terms and financial information that Plaintiff has requested. See Norman v. Vermont Office of the Court Administrator, 176 Vt. 593 (2004) (documents may be redacted in order to disclose information sought but also protect confidential employee data.) - 15 - WHEREFORE, Plaintiff respectfully prays this Court to: A) Declare that Defendant, being the functional equivalent of a Vermont public agency, is subject to the Vermont Public Records Act; B) Declare that the invoices and billing statements for sums paid to legal counsel Dinse, Knapp & McAndrew, P.C. in the relevant matters are public records and not exempt from disclosure under the Act; C) Enjoin the Defendant from withholding these documents from Plaintiff, ie: order the Defendant to comply with Plaintiff’s request within a reasonable period of time; D) Order that all requested documents and information be produced in electronic format, at no cost to Plaintiff; E) Award Plaintiff reasonable attorney’s fees and litigation costs. DATED at St. Johnsbury, Vermont on August 23, 2010. Respectfully submitted, David C. Sleigh Counsel for Prison Legal News - 16 -