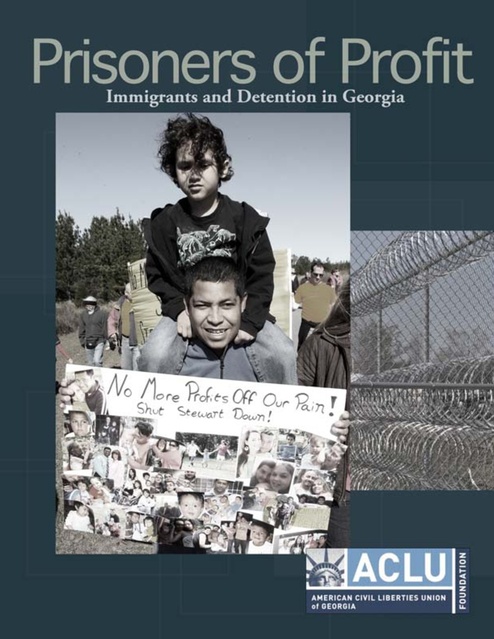

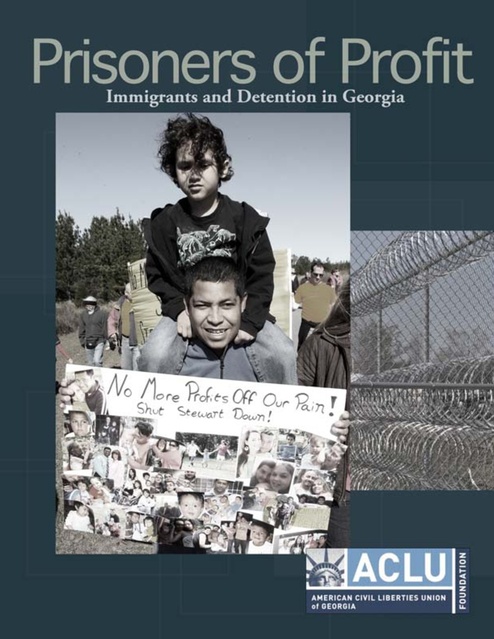

Georgia Aclu Prisoners of Profit Immigrants and Detention in Georgia 2012

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.