ICE Training Manual - Voluntary Departure Cheat Sheet - Removal Proceedings, NYOCC, 2007

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

Philip J. Costa, Deputy Chief Counsel, NYOCC

Genevieve Noble, Assistant Chief Counsel, NYOCC

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement

July 6, 2007

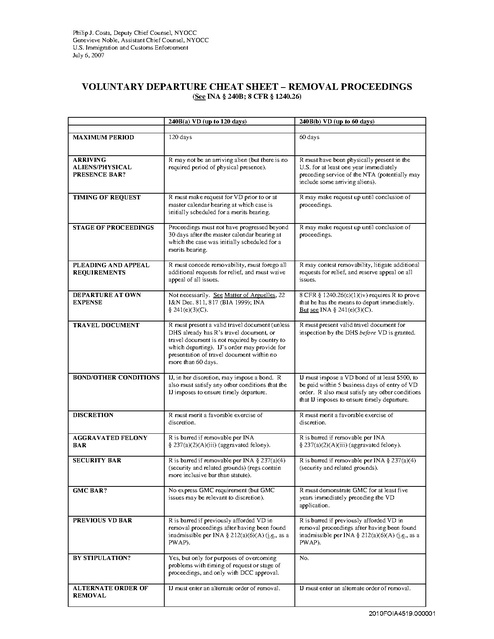

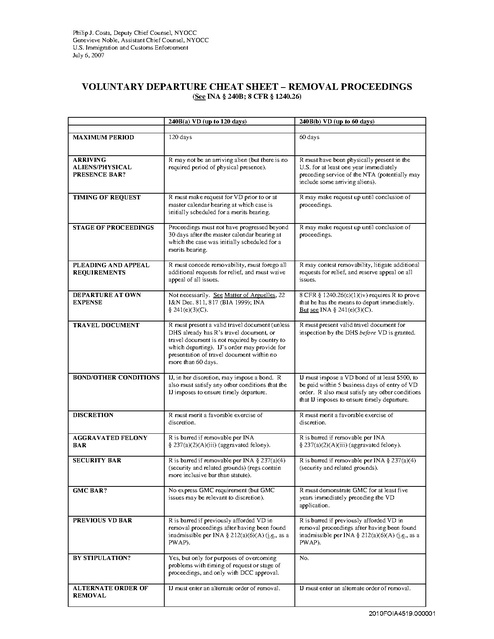

VOLUNTARY DEPARTURE CHEAT SHEET – REMOVAL PROCEEDINGS

(See INA § 240B; 8 CFR § 1240.26)

240B(a) VD (up to 120 days)

240B(b) VD (up to 60 days)

MAXIMUM PERIOD

120 days

60 days

ARRIVING

ALIENS/PHYSICAL

PRESENCE BAR?

R may not be an arriving alien (but there is no

required period of physical presence).

R must have been physically present in the

U.S. for at least one year immediately

preceding service of the NTA (potentially may

include some arriving aliens).

TIMING OF REQUEST

R must make request for VD prior to or at

master calendar hearing at which case is

initially scheduled for a merits hearing.

R may make request up until conclusion of

proceedings.

STAGE OF PROCEEDINGS

Proceedings must not have progressed beyond

30 days after the master calendar hearing at

which the case was initially scheduled for a

merits hearing.

R may make request up until conclusion of

proceedings.

PLEADING AND APPEAL

REQUIREMENTS

R must concede removability, must forego all

additional requests for relief, and must waive

appeal of all issues.

R may contest removability, litigate additional

requests for relief, and reserve appeal on all

issues.

DEPARTURE AT OWN

EXPENSE

Not necessarily. See Matter of Arguelles, 22

I&N Dec. 811, 817 (BIA 1999); INA

§ 241(e)(3)(C).

8 CFR § 1240.26(c)(1)(iv) requires R to prove

that he has the means to depart immediately.

But see INA § 241(e)(3)(C).

TRAVEL DOCUMENT

R must present a valid travel document (unless

DHS already has R’s travel document, or

travel document is not required by country to

which departing). IJ’s order may provide for

presentation of travel document within no

more than 60 days.

R must present valid travel document for

inspection by the DHS before VD is granted.

BOND/OTHER CONDITIONS

IJ, in her discretion, may impose a bond. R

also must satisfy any other conditions that the

IJ imposes to ensure timely departure.

IJ must impose a VD bond of at least $500, to

be paid within 5 business days of entry of VD

order. R also must satisfy any other conditions

that IJ imposes to ensure timely departure.

DISCRETION

R must merit a favorable exercise of

discretion.

R must merit a favorable exercise of

discretion.

AGGRAVATED FELONY

BAR

R is barred if removable per INA

§ 237(a)(2)(A)(iii) (aggravated felony).

R is barred if removable per INA

§ 237(a)(2)(A)(iii) (aggravated felony).

SECURITY BAR

R is barred if removable per INA § 237(a)(4)

(security and related grounds) (regs contain

more inclusive bar than statute).

R is barred if removable per INA § 237(a)(4)

(security and related grounds).

GMC BAR?

No express GMC requirement (but GMC

issues may be relevant to discretion).

R must demonstrate GMC for at least five

years immediately preceding the VD

application.

PREVIOUS VD BAR

R is barred if previously afforded VD in

removal proceedings after having been found

inadmissible per INA § 212(a)(6)(A) (i.e., as a

PWAP).

R is barred if previously afforded VD in

removal proceedings after having been found

inadmissible per INA § 212(a)(6)(A) (i.e., as a

PWAP).

BY STIPULATION?

Yes, but only for purposes of overcoming

problems with timing of request or stage of

proceedings, and only with DCC approval.

No.

ALTERNATE ORDER OF

REMOVAL

IJ must enter an alternate order of removal.

IJ must enter an alternate order of removal.

2010FOIA4519.000001

1)

Page 1 of 9

Alfred, Angela A

From:

Sent:

To:

(b)(6), (b)(7)(C)

@dhs.gov]

Friday, November 14, 2008 1:32 PM

(b)(6), (b)(7)(C)

Subject: NTA-requierment, Special Circumstances and Prosecutorial discretion

Chapter 2

Immigration Proceedings

2.2 Notice to Appear

I. INTRODUCTION

Removal proceedings, conducted under section 240 of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) to

determine the deportability or inadmissibility of an alien, are commenced by the filing of a Notice to

Appear (Form I-862) with the Immigration Court. 8 C.F.R. §§ 1003.14(a), 1239.1(a); Jimenez-Angeles

v. Ashcroft, 291 F.3d 594, 600 (9th Cir. 2002) (filing of NTA, not service on the alien, commenced

removal proceedings); Morales-Ramirez v. Reno, 209 F.3d 977, 981-82 (7th Cir. 2000); see generally

John J. Dvorske, Annotation, Commencement of Deportation Proceedings Under the Antiterrorism and

Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA) and Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act

(IIRIRA), 185 A.L.R. FED. 221 (2003). The NTA gives the alien notice of the charges of removability

against the alien under the Immigration and Nationality Act and the allegations of fact that make the

alien removable as charged.

II. PROSECUTORIAL DISCRETION

The Government’s decision whether to institute removal or other proceedings and what charges to bring

involves the exercise of prosecutorial discretion. Carranza v. INS, 277 F.3d 65 (1st Cir. 2002);

Chapinski v. Ziglar, 278 F.3d 718, 720-21 (7th Cir. 2002); Medina v. United States, 259 F.3d 220, 227

(4th Cir. 2001); Cabasug v. INS, 847 F.2d 132, 1324 (9th Cir. 1988); Johns v. Dept. of Justice, 653 F.2d

884, 890 (5th Cir. 1981); Matter of Bahta, 22 I&N Dec. 1381, 1391-1392 (BIA 2000); Memorandum

from the General Counsel to the Commissioner on INS Exercise of Prosecutorial Discretion (HQCOU

90/16-P). The Government is not required to advance every conceivable basis for removability in the

Notice to Appear. See De Faria v. INS, 13 F.3d 422, 424 (1st Cir. 1993).

Prosecutorial discretion is strongest when the matter involves the enforcement of immigration laws.

Harisiades v. Shaughnessy, 342 U.S. 580, 596-597 (1952). The Supreme Court has emphasized that the

defense of selective prosecution is generally unavailable in removal proceedings. The Court stated, “As

a general matter, ... an alien unlawfully in this country has no constitutional right to assert selective

enforcement as a defense against his deportation.” Reno v. American-Arab Anti-Discrimination

Committee, 525 U.S. 471, 491-492 (1999). The Board of Immigration Appeals has repeatedly held that

the decision whether to institute proceedings involves the exercise of prosecutorial discretion that

neither the Immigration Court nor the Board shall review. See Matter of Bahta, 22 I&N Dec. 1381,

1391-1392 (BIA 2000); Matter of G-N-C-, 22 I&N Dec. 281, 284 (BIA 1998); Matter of U-M-, 20 I&N

Dec. 327, 333 (BIA 1991); Matter of Ramirez-Sanchez, 17 I&N Dec. 503, 505 (BIA 1980); Matter of

2010FOIA4519.000002

7/12/2010

1)

Page 2 of 9

Marin, 16 I&N Dec. 581, 589 (BIA 1978); Matter of Geronimo, 13 I&N Dec. 680, 681 (BIA 1971).

The Government may cancel an NTA in its exercise of prosecutorial discretion before jurisdiction vests

with the Immigration Court. See Cortez-Felipe v. INS, 245 F.3d 1054 (9th Cir. 2001) (dismissing

petition to reinstate OSC served on alien but not filed with Immigration Court); Morales-Ramirez v.

Reno, 209 F.3d 977, 980-82 (7th Cir. 2000) (same); Matter of G-N-C-, 22 I&N Dec. 281, 283-284 (BIA

1998) (harmless error to terminate removal proceedings without considering the alien’s arguments); 8

C.F.R. § 1239.2(a). Once the Notice to Appear is filed with the Immigration Court, jurisdiction vests

with the court and removal proceedings commence. The Government then may move to dismiss

proceedings pursuant to applicable regulations. Id.; 8 C.F.R. § 1239.2(c).

There is no statute of limitations as to when deportation or removal proceedings may commence. Asika

v. Ashcroft, 362 F.3d 264, 268 (4th Cir. 2004) (no INA provision refers “to any time limitation on

deportation at all”); Biggs v. INS, 55 F.3d 1398, 1401 (9th Cir. 1995) (“Deportation in fact has no

statute of limitations.”); Costa v. INS, 233 F.3d 31, 38 (1st Cir. 2000) (“There is no set time either for

initiating a deportation proceeding or for filing a served OSC. Indeed, as we already have remarked, the

INS has virtually unfettered discretion in such respects.”); Matter of S-, 9 I&N Dec. 548, 553 (AG 1962)

(INA has no statute of limitations); cf. Dipeppe v. Quarantillo, 337 F.3d 326, 333-334 (3rd Cir. 2003)

(dismissing regulatory violation alleged in 8-year delay between service of OSC and placing alien case

before an Immigration Judge with an NTA, because in INA § 239(d)(2) Congress declared: “Nothing in

this subsection shall be construed to create any substantive or procedural right or benefit that is legally

enforceable by any party against the United States or its agencies or officers or any other person.”);

Campos v. INS, 62 F.3d 311, 314 (9th Cir. 1995) (INA provision, prohibiting construction of

amendment to create any substantive or procedural right or benefit that is legally enforceable by any

party against the United States or its agencies or officers or any other person, denied alien standing to

seek mandamus relief to obtain expedited deportation hearing before targeted date of release from

incarceration).

Moreover, the Government may not be estopped from seeking the deportation or removal of an alien

merely because of its delay. See INS v. Miranda, 459 U.S. 14, 18-19 (1982) (18-month delay by INS in

processing application for permanent residency did not estop INS); Montana v. Kennedy, 366 U.S. 308,

314-315 (1961) (failure to issue passport to pregnant mother did not estop Government to deny

citizenship to child born in Italy) ; Lopez-Urenda v. Ashcroft, 345 F.3d 788, 793 (9th Cir. 2003) (an

alien can have no settled expectations of being placed in deportation rather than removal proceedings);

Vasquez-Zavala v. Ashcroft, 324 F.3d 1105, 1108 (9th Cir.2003) (any expectation of being placed in

deportation proceedings that the alien might have had “could not support a sufficient expectation as to

when it would commence”); Uspango v. Ashcroft, 289 F.3d 226, 230 (3d Cir.2002) (no entitlement to

being placed in deportation rather than removal proceedings); Cortez-Felipe v. INS, 245 F.3d 1054 (9th

Cir. 2001) (same); Costa v. INS, 233 F.3d 31 (1st Cir. 2000) (same); Morales-Ramirez v. Reno, 209

F.3d 977, 980-82 (7th Cir. 2000) (same); Santamaria-Ames v. INS, 104 F.3d 1127, 1133 (9th Cir. 1996)

(“Mere file processing delay alone is insufficient to estop the government.”); United States v. UllysesSalazar, 28 F.3d 932, 937 (9th Cir. 1994), cert. denied, 514 U.S. 1020 (1995) (“The mere passage of

time is insufficient.”); Hamadeh v. INS, 343 F.2d 530, 532-533 (7th Cir. 1965) (four-year delay in

commencing deportation proceedings did not estop INS). In order for the Government to be estopped

from deporting alien because of delays involved in its investigation, the alien must show that

Government’s conduct amounted to affirmative misconduct and must show that misconduct was

prejudicial to him. Mendoza-Hernandez v. INS, 664 F.2d 635, 638 (7th Cir. 1981).

III.

CONTENTS OF A NOTICE TO APPEAR

2010FOIA4519.000003

7/12/2010

1)

Page 3 of 9

A.

Legal Sufficiency of a Notice to Appear

The Notice to Appear is designed to satisfy the due process requirement that the alien receive notice of

removal proceedings and an opportunity to be heard. See Landon v. Plasencia, 459 U.S. 21, 32-33

(1982); Hirsch v. INS, 308 F.2d 562, 567 (9th Cir. 1962). Charging documents are required to inform

aliens of the charges and allegations against them with enough precision to allow them to properly

defend themselves. Xiong v. INS, 173 F.3d 601, 608 (7th Cir. 1999); Macleod v. INS, 327 F.2d 453

(9th Cir. 1964); Takeo Tadano v. Manney, 160 F.2d 665, 667 (9th Cir. 1947); Matter of Raqueno, 17

I&N Dec. 10 (BIA 1979). However, “administrative pleadings are to be liberally construed.” VillegasValenzuela v. INS, 103 F.3d 805, 811 (9th Cir. 1996). Harmless clerical errors in the NTA do not affect

removability. Chowdhury v. INS, 249 F.3d 970, 973 n. 2 (9th Cir. 2001) (error in the NTA in citing the

statute that made the alien deportable).

Under section 239 of the Act, a Notice to Appear must specify:

The nature of the proceedings against the alien

The legal authority under which the proceedings are conducted.

z The acts or conduct alleged to be in violation of law.

z The charges against the alien and the statutory provisions alleged to have been violated.

z The alien may be represented by counsel and the alien will be provided (i) a period of time to

secure counsel and (ii) a current list of counsel who may be able to represent the alien at little or

no cost (commonly referred to as the “List of Legal Service Providers”)

z The requirement that the alien must immediately provide a written record of an address and

telephone number (if any) at which the alien may be contacted respecting proceedings under

section 240.

z The requirement that the alien must immediately provide a written record of any change of

address or telephone number.

• The consequences under section 240(b)(5) of the Act for failure to provide address and

telephone information.

• The time and place at which the proceedings will be held and the consequences under section

240(b)(5) of the Act of the failure, except under exceptional circumstances, to appear at removal

proceedings.

z

z

See INA § 239(a)(1); 8 C.F.R. § 1003.15.

Some of these requirements are satisfied in the boilerplate language found on the Notice to Appear. For

example, an alien’s right to be represented by an attorney or individual authorized to represent persons

before EOIR is clearly stated on the back of a Notice to Appear. The allegations and charge of

removability will satisfy the remaining requirements set forth in §239(a)(1) of the Act. Additionally, the

Service is required to provide certain administrative information to the Immigration Court. 8 C.F.R. §

1003.15(c).

When determining whether a Notice to Appear is legally sufficient keep in mind the following: (a) Are

the charges appropriate and accurate? (b) Do the factual allegations support the charge of removability?

and (c) Is there evidence to establish the factual allegations and charge of removability? If the Service

alleges the alien has been admitted but is now removable, there should be an allegation setting forth the

alien’s admission. Conversely, if the alien is present in the United States without having been admitted

or paroled there should be an allegation detailing the method of entry into the United States.

2010FOIA4519.000004

7/12/2010

1)

Page 4 of 9

Practice Tip: Is the alien charged under the correct section of law? Arriving aliens

and aliens present in the United States who have not been admitted or paroled should

only be charged under section 212 of the Act. Conversely, aliens who have been

admitted but are now deportable should only be charged under section 237 of the Act.

B.

Officers Authorized to Issue a Notice to Appear

Only those officers specifically authorized by regulation may issue a Notice to Appear. 8 C.F.R. §

1239.1. Any immigration officer performing an inspection of an arriving alien at a port-of-entry may

issue a Notice to Appear to such an alien. Id. In addition, the following officers (or officers acting in

such capacity) may issue a Notice to Appear:

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

District directors (except foreign);

Deputy district directors (except foreign);

Chief patrol agents;

Deputy chief patrol agents;

Assistant chief patrol agents;

Patrol agents in charge;

Assistant patrol agents in charge;

Field operations supervisors;

Special operations supervisors;

Supervisory border patrol agents;

Service center directors;

Deputy service center directors;

Assistant service center directors for examinations;

Supervisory district adjudications officers;

Supervisory asylum officers;

Officers in charge (except foreign);

Assistant officers in charge (except foreign);

Special agents in charge;

Deputy special agents in charge;

Associate special agents in charge;

Assistant special agents in charge;

Resident agents in charge;

Supervisory special agents;

Directors of investigations;

District directors for interior enforcement;

Deputy or assistant district directors for interior enforcement;

Director of detention and removal;

Field office directors;

Deputy field office directors;

Supervisory deportation officers;

Supervisory detention and deportation officers;

2010FOIA4519.000005

7/12/2010

1)

Page 5 of 9

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

Directors or officers in charge of detention facilities;

Directors of field operations;

Deputy or assistant directors of field operations;

District field officers;

Port directors;

Deputy port directors; or

Other officers of employees of the Department of Homeland Security or of the United States who

are delegated the authority as provided by 8 C.F.R. § 2.1 to issue notices to appear.

8 C.F.R. § 1239.1.

The issuing officer’s signature is found in the lower right corner of the front of the Notice to Appear.

Ideally, the officer’s name and title should be listed to ensure an authorized individual has issued the

document.

C.

Asylees and Refugees

Removal proceedings should not commence against an alien who has received asylum, withholding of

removal, or refugee status, and still has that status, until procedures to revoke the status have begun. 8

C.F.R. §§ 207.9, 1208.24. The Government should give notice of intent to terminate asylum,

withholding or refugee status before, or simultaneous with, the filing of any NTA. Id. The Asylum

Office issues the notice of intent to terminate if it had granted the status. 8 C.F.R. § 1208.24. If an

Immigration Court granted the alien asylum or withholding, no NTA may be filed but a motion to

reopen proceedings should be filed with a notice of intent to terminate status.

D.

Temporary Resident Aliens

The Ninth Circuit has explained that the Government need no longer terminate a respondent’s temporary

resident status under INA § 245A before commencing removal proceedings:

In Matter of Medrano, the BIA held that, as a condition precedent to the commencement

of a deportation proceeding, the INS was required to terminate the temporary resident

status of an alien who commits a deportable offense after acquiring temporary resident

status.

However, this requirement has been eliminated by 8 C.F.R. § 245a.2(u)(2)(ii), which

became effective on May 31, 1995. This section provides for the institution of

deportation proceedings and the automatic termination of temporary resident status upon

the entry of a final order of deportation in certain cases, including those where the basis

for deportation is an aggravated felony conviction. See 8 U.S.C. § 1251(a)(2)(A)(iii)

(providing for the deportation of convicted aggravated felons).

Perez v. INS, 72 F.3d 256, 258 n. 2 (2d Cir. 1995).

E. Members of U.S. Armed Forces

The Special Agent in Charge (SAC) must request authorization from Marco Salazar, Interim Chief,

Public Safety, HQ, before issuance of an NTA against current members of the United States armed

forces. John Clark signs off on the request. Former Section 14.2(d)(7) of the Special Agent’s Field

Manual (M-490), former Standard Operating Procedures for Enforcement Officers (SOP) § V.D.7. and

2010FOIA4519.000006

7/12/2010

1)

Page 6 of 9

former Operating Instructions (O.I.) § 242.1(a)(18) restricted issuance of an NTA against current or

former members of the U.S. armed forces. The O.I.’s were rescinded effective June 24, 1997. See

generally Reno v. American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, 525 U.S. 471, 484 n. 8 (1999)

(noting that “internal INS guidelines ... were apparently rescinded on June 27, 1997”). Current policy is

that an NTA should not issue against an alien who is a current or former member of the U.S. military

and who is eligible for naturalization under sections 328 or 329 of the NTA, notwithstanding

removability. The character of military service and the basis for removal should be considered before

issuance of the NTA. See Memorandum from the Acting Director of the ICE Office of Investigations

entitled “Issuance of Notices to Appear, Administrative Orders of Removal, or Reinstatement of a Final

Removal Order on Aliens with United States Military Service” (June 21, 2004).

F.

Diplomats

Section 14.2(d)(.87) of the Special Agent’s Field Manual (M-490) restricts issuance of an NTA against

aliens who appear to have diplomatic status:

Processing diplomats. Before you may issue a Notice to Appear against an alien who may

have diplomatic status, you must contact the State Department to ensure that diplomatic

status no longer exists and that there is no diplomatic immunity from legal process.

Contact the State Department by completely filling out Form I-566 and sending it by

facsimile, or relay the information by telephone and record the response.

This provision does not necessarily create a judicially enforceable right. See Pasquini v. Morris, 700

F.2d 658, 662 (11th Cir.1983) (holding that “[t]he internal operating procedures of the INS are for the

administrative convenience of the INS only”); Dong Sik Kwon v. INS, 646 F.2d 909, 918-19 (5th

Cir.1981) (stating that INS operations instructions “do not have the force of law”); but see Nicholas v.

INS, 590 F.2d 802, 806 (9th Cir.1979) (determining that INS guideline “far more closely resembles a

substantive provision for relief than an internal procedural guideline”).

III. ADDITIONAL LODGED CHARGES

The Government may lodge additional charges during removal proceedings. 8 C.F.R. §§ 1003.30,

1240.10(e); Hirsch v. INS, 308 F.2d 562, 567 (9th Cir. 1962); Crain v. Boyd, 237 F.2d 927, 931 (9th

Cir. 1956); Galvan v. Press, 201 F.2d 302, 307 (9th Cir. 1953), aff’d, 347 U.S. 522 (1954); U. S. ex rel.

Sollazzo v. Esperdy, 187 F.Supp. 753, 755 (S.D.N.Y. 1960), aff’d, 285 F.2d 341 (2d Cir. 1961), cert.

denied, 366 U.S. 905 (1961). The alien may be granted a reasonable continuance to respond to the

lodged charge(s) or allegation(s) contained in the Form I-261. Id. Due process is violated if removal is

based on a ground of removability of which the Government fails to give the alien adequate notice.

Chowdhury v. INS, 249 F.3d 970 (9th Cir. 2001); Xiong v. INS, 173 F.3d 601, 608 (7th Cir. 1999). But

there is no set rule about the period of notice required.

When a possible ground of excludability developed during the course of an exclusion hearing, the

Immigration Court could rule upon the ground if the alien was informed of the issue at some point

during the hearing and the alien was given a reasonable opportunity to respond. Matter of Salazar, 17

I&N Dec. 167, 169 (BIA 1979), cited in, INS v. Lopez-Mendoza, 468 U.S. 1032 (1984); see also

Yamataya v. Fisher (The Japanese Immigrant Case), 189 U.S. 86, 100-102 (1903) (oral notice of

grounds of deportability satisfied due process); Siniscalchi v. Thomas, 195 Fed. 701 (6th Cir. 1912)

(deportation lawfully based on ground of deportability that developed during hearing). Nevertheless, the

best practice is to amend the charging document by serving the alien with a Form I-261 and lodging it

with the Immigration Court a reasonable period of time before the hearing. See 8 C.F.R. §§ 1003.30,

2010FOIA4519.000007

7/12/2010

1)

Page 7 of 9

1240.10(e); Snajder v. INS, 29 F.3d 1203 (7th Cir. 1994) (IJ erred in failing to re-advise alien of right to

counsel after INS lodged additional charge).

IV.

SERVICE OF THE NOTICE TO APPEAR

A.

Generally

Due process requires that aliens receive notice of their removal hearings that is reasonably calculated to

reach them. See Dobrota v. INS, 311 F.3d 1206, 1210 (9th Cir. 2002). Section 239 specifies how

service of the Notice to Appear is to be made. INA § 239(a), (c); Matter of G-Y-R-, 23 I&N Dec. 181

(BIA 2001). The NTA must be given in person to the alien, or if personal service is not practicable,

[1]

through service by mail to the alien or the alien’s counsel of record, if any.

Id. Notice to the alien’s

counsel or representative is deemed notice to the alien. See INA § 240(b)(5)(A); 8 C.F.R. § 1292.5(a);

Garcia v. INS, 222 F.3d 1208, 1209 (9th Cir. 2000) (notice was adequate where served only upon

petitioners' attorney); Wijeratne v. INS, 961 F.2d 1344, 1347 (7th Cir. 1992) (notice received by alien's

accredited representative was sufficient); Sewak v. INS, 900 F.2d 667, 670 n. 6 (3d Cir. 1990); ReyesArias v. INS, 866 F.2d 500, 503 (D .C. Cir. 1989) (service of a notice of hearing to an alien’s counsel is

sufficient to afford notice to the alien); Chang v. Jiugni, 669 F.2d 275, 277 (5th Cir. 1982); Matter of

Rivera-Claros, 21 I&N Dec. 599, 602 (BIA 1996).

Notice is sufficient if it is provided by mail to the most recent address provided by the alien. INA § 240

(b)(5)(A); 8 C.F.R. § 1003.26(d).

The rule is well settled that if a letter properly directed is proved to have been either put

into the post-office or delivered to the postman, it is presumed, from the known course of

business in the post-office department, that it reached its destination at the regular time,

and was received by the person to whom it was addressed.

Busquets-Ivars v. Ashcroft, 333 F.3d 1008, 1009 (9th Cir. 2003), quoting Rosenthal v. Walker, 111 U.S.

185, 193 (1884). However, a sworn affidavit of nonreceipt from the addresse can rebut the

presumption. Salta v. INS, 314 F.3d 1076, 1079 (9th Cir. 2002). If the notice is sent using an incorrect

zip code, there is no presumption of proper delivery. Busquets-Ivars v. Ashcroft, 333 F.3d 1008 (9th

Cir. 2003).

The Government may use certified mail to gain a stronger presumption of delivery. See Salta v. INS,

314 F.3d 1076, 1079 (9th Cir.2002); Matter of Grijalva, 21 I&N Dec. 27, 32 (BIA 1995) (allowing an

alien to be charged with receipt when the certified mail receipt has been signed “by the respondent or a

responsible person at the respondent's address”). If the Government cannot produce a return receipt for

the mailed notice, any presumption of delivery disappears. See Busquets-Ivars v. Ashcroft, 333 F.3d

1008, 1009 (9th Cir. 2003) (cases cited therein); Matter of G-Y-R-, 23 I&N Dec. 181 (BIA 2001).

However, the alien’s refusal to accept delivery of certified mail does not invalidate service of the NTA.

See Fuentes-Argueta v. INS, 101 F.3d 867, 871 (2nd Cir.1996) (concluding in absentia deportation

allowed if notice of hearing sent by certified mail was returned unclaimed); Matter of M-D-, 23 I&N

Dec. 540, 542 (BIA 2002) (same). “An alien does not have to actually receive notice of a deportation

hearing in order for the requirements of due process to be satisfied.” Farhoud v. INS, 122 F.3d 794, 796

(9th Cir. 1997) (receipt of certified mail by someone other than the alien at the address he provided was

sufficient); Tapia v. Ashcroft, 351 F.3d 795, 798 (7th Cir. Dec 16, 2003) (same).

2010FOIA4519.000008

7/12/2010

1)

Page 8 of 9

Service of a Notice to Appear automatically terminates parole. See 8 C.F.R. § 1212.5(e)(2)(i) (“When a

charging document is served on the alien, the charging document will constitute written notice of

termination of parole, unless otherwise specified.”). Service of the NTA also stops accrual of

continuous residence or continuous physical presence for cancellation of removal. See INA 240A(d)(1);

Matter of Mendoza-Sandino, 22 I&N Dec. 1236 (BIA 2000).

B.

Juveniles

Special care must be taken in the case of juveniles under age 14 because they cannot be personally

served with the NTA. See 8 C.F.R. §§ 1103.5a(c)(2)(ii), 1236.2(a) (providing that service on an alien

under 14 years of age shall be made on the person with whom the minor resides). Usually service of the

NTA must be made on their parents:

The regulations governing service of a notice to appear on a minor respondent do not

explicitly require service on the parent or parents in all circumstances. If a minor

respondent's parents are not present in this country, service on an uncle or other near

relative accompanying the child may suffice. However, when it appears that the minor

child will be residing with her parents in this country, as in this case, the regulation

requires service on the parents, whenever possible, in addition to service that may be

made on an accompanying adult or more distant relative. Therefore, under the facts in

this case, we find that the Immigration Judge correctly determined that the Service failed

to demonstrate clear, unequivocal, and convincing evidence of proper service of the

Notice to Appear.

Matter of Mejia-Andino, 23 I&N Dec. 533, 536-537 (BIA 2002) (footnotes omitted).

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit has concluded that the any adult who receives custody of a

minor alien from DHS must be served with the charging document and hearing notice, despite 8 C.F.R.

§ 1103.5a(c)(2)(ii) that only requires this service if the minor is under the age of 14. Flores-Chavez v.

Ashcroft, 362 F.3d 1150, 1156-1157

(9th Cir. 2004).

Service of an NTA issued against a minor may properly be made on the director of a facility in which

the minor is detained. See 8 C.F.R. §§ 103.5a(c)(2)(ii), 1236.2(a); Matter of Amaya, 21 I&N Dec. 583,

584-585 (BIA 1996).

C.

Confined and Mentally Incompetent Aliens

Service of the NTA on confined aliens is on the alien and his custodian, except where the confined alien

is mentally incompetent service is only on the custodian:

If a person is confined in a penal or mental institution or hospital and is competent to

understand the nature of the proceedings initiated against him, service shall be made both

upon him and upon the person in charge of the institution or the hospital. If the confined

person is not competent to understand, service shall be made only on the person in charge

of the institution or hospital in which he is confined, such service being deemed service

on the confined person.

8 C.F.R. § 103.5a(c)(2)(i).

Personal service, or service by mail if personal service is not practicable, of the NTA is to be made on

the custodian of the confined or mentally incompetent alien. Compare 8 C.F.R. §§ 103.5a(c)(2)(ii) and

1239.1(b) with INA §239(a)(1). “In case of mental incompetency, whether or not confined in an

institution, … service shall be made upon the person with whom the incompetent or the minor resides.”

8 C.F.R. § 103.5a(c)(2)(ii).

2010FOIA4519.000009

7/12/2010

1)

Page 9 of 9

D.

Initial Hearing after NTA Served

Unless requested by the alien, no hearing will be scheduled earlier than ten days from the date of service

of the NTA. The delay is to allow the alien the opportunity to obtain counsel. INA § 239(b). Should

the alien seek a prompt hearing, the alien should execute the section entitled “Request for Prompt

Hearing.” If an alien is not properly served with the NTA but he appears in court, the NTA may be

served on him or her at that time, but the alien may have ten days to prepare and to obtain counsel. See

INA § 239(b)(1).

E.

Consequences of Improper Service of the NTA

If an alien is not properly served with the NTA, jurisdiction never vests with the Immigration Court. If

the alien fails to appear after improper service, the Immigration Judge will dismiss or terminate

proceedings. Matter of Lopez-Barrios, 20 I&N Dec. 203 (BIA 1990). The Service will have to effect

proper service at a later time. When an alien properly served with an NTA fails to appear at removal

proceedings, the Immigration Judge shall enter an in absentia order of removal if the alien is removable.

See INA § 239(b)(5)(A); 8 C.F.R. § 1003.26(c).

In Matter of G-Y-R-, 23 I&N Dec. 181 (BIA 2001), the Board held that in absentia order of removal is

inappropriate where the alien did not receive the NTA served by certified mail and the alien’s address of

record was several years old. An alien who is ordered removed without receiving proper service of the

NTA may move to reopen proceedings. See INA § 240(b)(5)(C)(ii); 8 C.F.R. § 1003.23(b)(4)(ii). The

alien who alleges improper service of the NTA shall not be removed during pendency of his or her

motion to reopen. INA § 240(b)(5)(C).

[1]

The BIA held that, for EOIR notice purposes, in-person-service was not practicable if the alien was not present in court.

See Matter of Grijalva, 21 I&N Dec. 27, 34-35 (BIA 1995).

2010FOIA4519.000010

7/12/2010

IMMIGRATION CONSEQUENCES OF CONVICTIONS SUMMARY CHECKLIST*

GROUNDS FOR DEPORTATION [apply to

lawfully admitted noncitizens, such as a lawful

permanent resident [LPR] – greencard holder]

Aggravated Felony conviction

➢ Consequences (in addition to deportability):

◆ Ineligibility for most waivers of removal

◆ Ineligibility for voluntary departure

◆ Permanent inadmissibility after removal

◆ Subjects client to up to 20 years of prison if s/he

illegally reenters the U.S. after removal

➢ Crimes covered (possibly even if not a felony):

◆ Murder

◆ Rape

◆ Sexual Abuse of a Minor

◆ Drug Trafficking [probably includes any felony

controlled substance offense; may include

misdemeanor marijuana sale offenses and 2nd

misdemeanor possession offenses]

◆ Firearm Trafficking

◆ Crime of Violence + 1 year sentence**

◆ Theft or Burglary + 1 year sentence**

◆ Fraud or tax evasion + loss to victim(s) > $10,000

◆ Prostitution business offenses

◆ Commercial bribery, counterfeiting, or forgery +

1 year sentence**

◆ Obstruction of justice offenses + 1 year sentence**

◆ Certain bail-jumping offenses

◆ Various federal criminal offenses and possibly state

analogues [money laundering, various federal

firearms offenses, alien smuggling, etc.]

◆ Attempt or conspiracy to commit any of the above

Controlled Substance conviction

➢ EXCEPT a single offense of simple possession of 30g

or less of marijuana

Crime Involving Moral Turpitude [CIMT] conviction

➢ For crimes included, see Grounds of Inadmissibility

➢ An LPR is deportable for 1 CIMT committed within

5 years of admission into the U.S. and for which a

sentence of 1 year or longer may be imposed

➢ An LPR is deportable for 2 CIMT committed at any

time “not arising out of a single scheme”

Firearm or Destructive Device conviction

Domestic Violence conviction or other domestic

offenses, including:

➢ Crime of domestic violence

➢ Stalking

➢ Child abuse, neglect or abandonment

➢ Violation of order of protection (criminal or civil)

GROUNDS OF INADMISSIBILITY [apply

to noncitizens seeking lawful admission,

including LPRs who travel out of US]

Conviction or admitted commission of a

Controlled Substance Offense, or DHS

(formerly INS) has reason to believe

individual is a drug trafficker

➢ No 212(h) waiver possibility (except for

a single offense of simple possession of

30g or less of marijuana)

Conviction or admitted commission of a

Crime Involving Moral Turpitude [CIMT]

➢ This category covers a broad range of

crimes, including:

◆ Crimes with an intent to steal or

defraud as an element [e.g., theft,

forgery]

◆ Crimes in which bodily harm is

caused or threatened by an

intentional act, or serious bodily

harm is caused or threatened by a

reckless act [e.g., murder, rape, some

manslaughter/assault crimes]

◆ Most sex offenses

➢ Petty Offense Exception—for one CIMT

if the client has no other CIMT + the

offense is not punishable > 1 year (e.g.,

in New York can’t be a felony) + does

not involve a prison sentence > 6

months

Prostitution and Commercialized Vice

Conviction of 2 or more offenses of any

type + aggregate prison sentence of

5 years

INELIGIBILITY FOR

U.S. CITIZENSHIP

Certain convictions or

admissions of crime will

statutorily bar a finding

of good moral character

for up to 5 years:

➢ Controlled

Substance Offense

[except in case 30g

of marijuana]

➢ Crime Involving

Moral Turpitude

➢ 2 or more offenses

of any type +

aggregate prison

sentence of

5 years

➢ 2 gambling

offenses

➢ Confinement to a

jail for an aggregate

period of 180 days

Aggravated felony

may bar a finding of

moral character forever,

and thus may make

your client permanently

ineligible for citizenship

INELIGIBILITY FOR LPR CANCELLATION OF REMOVAL

➢ Aggravated Felony Conviction

➢ Offense covered under Ground of Inadmissibility when committed

within the first 7 years of residence after admission in the U.S.

INELIGIBILITY FOR ASYLUM OR WITHHOLDING OF REMOVAL BASED

ON THREAT TO LIFE OR FREEDOM IN COUNTRY OF REMOVAL

“Particularly serious crimes” make noncitizens ineligible for asylum

and withholding. They include:

➢ Aggravated felonies

◆ All will bar asylum

◆ Aggravated felonies with aggregate 5 year sentence of

imprisonment will bar withholding

◆ Aggravated felonies involving unlawful trafficking in controlled

substances will presumptively bar withholding

➢ Other serious crimes—no statutory definition [For sample case law

determinations, see Appendix F in NYSDA Immigration Manual]

CONVICTION DEFINED

“A formal judgment of guilt of the alien entered by a court or, if adjudication of guilt has been withheld, where:

(i) a judge or jury has found the alien guilty or the alien has entered a plea of guilty or nolo contendere or has admitted

sufficient facts to warrant a finding of guilt, AND

(ii) the judge has ordered some form of punishment, penalty, or restraint on the alien’s liberty to be imposed.”

THUS:

◆ A drug treatment or domestic violence counseling alternative to incarceration disposition could be considered a conviction for

immigration purposes if a guilty plea is taken (even if the guilty plea is or might later be vacated)

◆ A deferred adjudication disposition without a guilty plea (e.g., NY ACD) will not be considered a conviction

◆ A youthful offender adjudication will not be considered a conviction if analogous to a federal juvenile delinquency disposition

(e.g., NY YO)

**This summary checklist was originally prepared by former NYSDA Immigrant Defense Project Staff Attorney Sejal Zota. Because this checklist is frequently

updated, please visit our Internet site at <http://www.nysda.org> (click on Immigrant Defense Project page) for the most up-to-date version.

**The 1-year requirement refers to an actual or suspended prison sentence of 1 year or more [A New York straight probation or conditional discharge

without a suspended sentence is not considered a part of the prison sentence for immigration purposes.]

(5/03)

2010FOIA4519.000011

Copyright © 2003 New York State Defenders Association

Office ofthe

oflhe Principal Legal Advisor

Homeland Security

U.S. Department of liomelnnd

425 rJ Street,

Stree~ NW

Washington, DC 20536

u.s. Immigration

and Customs

Enforcement

October 24, 2005

MEMORANDUM FOR:

All OPLA Chief Counsel

FROM:

William J.

Principal Legal Ad~ilor

Ad~i"dor

Ad~aor

SUBJECT:

Prosecutorial Discretion

Howardl\(\~

Howardl\()~

As you know, when Congress abolished the Immigration and Naturalization Service

and divided its functions among U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE),

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration

Services (CIS), the Office of the Principal Legal Advisor (OPLA) was given exclusive

authority to prosecute all removal proceedings. See Homeland Security Act of2002,

Pub. L. No. 107-296, § 442(c), 116

I I 6 Stat. 2135, 2194 (2002) ("the legal advisor * * *

shall represent the bureau in all

a]] exclusion, deportation, and removal proceedings before

the Executive Office for Immigration Review"). Complicating matters for OPLA is

that our cases come to us from CBP, CIS, and ICE, since all three bureaus are

authorized to issue Notices to Appear (NTAs).

OPLA is handling about 300,000 cases in the immigration courts, 42,000 appeals before

the Board oflmmigration

ofImmigration Appeals (BIA

(BlA

(BLA or Board), and 12,000 motions to reopen each

year. Our circumstances in litigating these cases differ in a major respect from our

predecessor, the INS's Office of General Counsel. Gone are the days when INS district

counsels, having chosen an attorney-client model that required client consultation

before INS trial attorneys could exercise prosecutorial discretion, could simply walk

down the hall to an INS district director, immigration agent, adjudicator, or border

patrol officer to obtain the client's permission to proceed with that exercise. Now

NTA-issuing clients or stakeholders might be in different agencies, in different

buildings, and in different cities from our own.

Since the NTA-issuing authorities are no longer all under the same roof, adhering to

INS OGC's attorney-client model would minimize our efficiency. This is particularly

so since we are litigating our hundreds of thousands of cases per year with only 600 or

so attorneys; that our case preparation time is extremely limited, averaging about 20

minutes a case; that our caseload will increase since Congress is now providing more

resources for border and interior immigration enforcement; that

tbat many of the cases that

come to us from NTA-issuers lack supporting evidence like conviction documents; that

we must prioritize our cases to allow

a]]ow us to place greatest emphasis on our national

security and criminal alien dockets; that we have growing collateral duties such as

WWW.lce.gov

www.lce.gov

\VWW.lce.gov

2010FOIA4519.000012

All OPLA Chief Counsel

Page 2 of9

assisting the Department of Justice with federal court litigation; that in many instances

we lack sufficient staff to adequately brief Board appeals or oppositions to motions to

reopen; and that the opportunities to exercise prosecutorial discretion arise at many

different points in the removal process.

To elaborate on this last point, the universe of opportunities to exercise prosecutorial

discretion is large. Those opportunities arise in the pre-filing stage, when, for example,

we can advise clients who consult us whether or not to file NTAs or what charges and

evide~ce to base them on. They arise in the course of litigating the NTA in

immigration court, when we may want, among other things, to nl0ve to dismiss a case

as legally insufficient, to amend the NTA, to decide not to oppose a grant of relief, to

join in a motion to reopen, or to stipulate to the admission of evidence. They arise after

the immigration judge has entered an order, when we must decide whether to appeal all

or part of the decision. Or they nlay arise in the context of ORO's decision to detain

aliens, when we must work closely with DRO in connection with defending that

decision in the administrative or federal courts. In the 50-plus immigration courtrooms

across the United States in which we litigate, OPLA's trial attorneys continually face

these and other prosecutorial discretion questions. Litigating with maximum efficiency

requires that we exercise careful yet quick judgment on questions involving

prosecutorial discretion. This will require that OPLA's trial attorneys become very

familiar with the principles in this memorandum and how to apply them.

Further giving lise to the need for this guidance is the extraordinary volume of

immigration cases that is now reaching the United States Coutis of Appeals. Since

2001, federal court immigration cases have tripled. That year, there were 5,435 federal

court cases. Four years later, in fiscal year 2004, that number had risen to 14,699

federal court cases. Fiscal year 2005 federal court immigration cases will approximate

15,000. The lion's share of these cases consists of petitions for review in the United

States Courts of Appeal. Those petitions are now overwhelming the Department of

Justice's Office of hnmigration Litigation, with the result that the Department of Justice

has shifted responsibility to brief as many as 2,000 of these appellate cases to other

Departmental conlponents and to the U.S. Attorneys' Offices. This, as you know, has

brought you into greater contact with Assistant U.S. Attorneys who are turning to you

for assistance in remanding some of these cases. This memorandum is also intended to

lessen the nUlnber of such renland requests, since it provides your office with guidance

to assist you in eliminating cases that would later nlerit a relnand.

Given the complexity of imlnigration law, a complexity that federal courts at all levels

routinely acknowledge in published decisions, your expert assistance to the U.S.

Attorneys is critical. I It is all the more important because the decision whether to

1 As you know, if and when your resources permit it, I encourage you to speak with your respective

United States Attorneys' Offices about having those Offices designate Special Assistant U.S. Attonleys

from OPLA's ranks to handle both civil and criminal federal court immigration litigation. The U.S.

2010FOIA4519.000013

All OPLA Chief Counsel

Page 3 of9

proceed with litigating a case in the federal courts must be gauged for reasonableness,

lest, in losing the case, the courts award attorneys' fees against the government pursuant

to the Equal Access to Justice Act, 28 U.S.C. 2412. In the overall scheme of litigating

the removal of aliens at both the administrative and federal court level, litigation that

often takes years to complete, it is important that we all apply sound principles of

prosecutorial discretion, uniformly throughout our offices and in all of our cases, to

ensure that the cases we litigate on behalf of the United States, whether at the

administrative level or in the federal courts, are truly worth litigating.

**********

With this background in mind, I am directing that all OPLA attorneys apply the

following principles of prosecutorial discretion:

1) Prosecutorial Discretion Prior to or in Lieu of NTA Issuance:

In the absence of authority to cancel NTAs, we should engage in client liaison with

CBP, CIS (and ICE) via, or in conjunction with, CIS/CBP attorneys on the issuance of

NTAs. We should attempt to discourage issuance of NTAs where there are other

options available such as administrative removal, crewman removal, expedited removal

or reinstatement, clear eligibility for an immigration benefit that can be obtained outside

of immigration court, or where the desired result is other than a removal order.

It is not wise or efficient to place an alien into proceedings where the intent is to allow

that person to remain unless, where compelling reasons exist, a stayed removal order

might yield enhanced law enforcement cooperation. See Attachment A (Memorandum

from Wesley Lee, ICE Acting Director, Office of Detention and Removal, Alien

Witnesses and Informants Pending Removal (May 18, 2005)); see also Attachment B

(Detention and Removal Officer's Field Manual, Subchapters 20.7 and 20.8, for further

explanation on the criteria and procedures for stays of removal and deferred action).

Examples:

• Immediate Relative of Service Person- If an alien is an immediate relative of a

military service member, a favorable exercise of discretion, including not issuing an

NTA, should be a prime consideration. Military service includes current or fonner

members of the Armed Forces, including: the United States Army, Air Force, Navy,

Marine Corps, Coast Guard, or National Guard, as well as service in the Philippine

Scouts. OPLA counsel should analyze possible eligibility for citizenship under

Attorneys' Offices will benefit greatly from OPLA SAUSAs, especially given the immigration law

expertise that resides in each of your Offices, the immigration law's great complexity, and the extent to

which the USAOs are now overburdened by federal immigration litigation.

2010FOIA4519.000014

AU OPLA Chief Counsel

Page 4 of9

sections 328 and 329. See Attachment C (Memorandum from Marcy M. Forman~

Director, Office of Investigations, Issuance of Notices to Appeal, Administrative

Orders of Removal, or Reinstatement of a Final Removal Order on Aliens with

United States Military Service (June 21, 2004».

•

Clearly Approvable 1-130/1-485- Where an alien is the potential beneficiary of

a clearly approvable 1-130/1-485 and there are no serious adverse factors that

otherwise justify expulsion, allowi.ng the alien the opportunity to legalize his or her

status through a CIS-adjudicated adjustment application can be a cost-efficient

option that conserves immigration court time and benefits someone who can be

expected to become a lawful permanent resident of the United States. See

Attachment D (Memorandum from William J. Howard, OPLA Principal Legal

Advisor, Exercising Prosecutorial Discretion to Dismiss Adjustment Cases (October

6, 2005)).

• Administrative Voluntary Departure- We may be consulted in a case where

administrative voluntary departure is being considered. Where an alien is eligible

for voluntary departure and likely to depart, OPLA attorneys are encouraged to

facilitate the grant of administrative voluntary departure or voluntary departure

under safeguards. This may include continuing detention if that is the likely end

result even should the case go to the Immigration Court.

•

NSEERS Failed to Register- Where an alien subject to NSEERS registration

failed to timely register but is otherwise in status and has no criminal record, he

should not be placed in proceedings ifhe has a reasonable excuse for his failure.

Reasonably excusable failure to register includes the alien's hospitalization,

admission into a nursing home or extended care facility (where mobility is severely

limited); or where the alien is simply unaware of the registration requirements. See

Attachment E (Memorandum from Victor Cerda, OPLA Acting Principal Legal

Advisor, Changes to the National Security Entry Exit Registration System

(NSEERS)(January 8,2004)).

• Sympathetic Humanitarian Factors- Deferred action should be considered

when the situation involves sympathetic humanitarian circumstances that rise to

such a level as to cry for an exercise of prosecutorial discretion. Examples of this

include where the alien has a citizen child with a serious medical condition or

disability or where the alien or a close family member is undergoing treatment for a

potentially life threatening di.sease. DHS has the most prosecutorial discretion at

this stage of the process.

2) Prosecutorial Discretion after the Notice to Appear has issued, but before

the Notice to Appear has been flIed:

We have an additional opportunity to appropriately resolve a case prior to

expending court resources when an NTA has been issued but not yet filed with the

immigration court. This would be an appropriate action in any of the situations

2010FOIA4519.000015

All OPLA Chief Counsel

Page 5 of9

identified in #1. Other situations may also arise where the reasonable and rational

decision is not to prosecute the case.

Example:

• U or T visas- Where a ~~U" or "T" visa application has been submitted, it

may be appropriate not to file an NTA until a decision is made on such an

application. In the event that the application is denied then proceedings

would be appropriate.

3) Prosecutorial Discretion after NTA Issuance and Filing:

The filing of an NTA with the Immigration Court does not foreclose further

prosecutorial discretion by OPLA Counsel to settle a matter. There may be

ample justification to move the court to terminate the case and to thereafter

cancel the NTA as improvidently issued or due to a change in circumstances

such that continuation is no longer in the government interest. 2 We have

regulatory authority to dismiss proceedings. Dismissal is by regulation without

prejudice. See 8 CFR §§ 239.2(c), 1239.2(c). In addition, there are numerous

opportunities that OPLA attorneys have to resolve a case in the immigration

court. These routinely include not opposing relief, waiving appeal or making

agreements that narrow issues, or stipulations to the admissibility of evidence.

There are other situations where such action should also be considered for

purposes ofjudicial economy, efficiency of process or to promote justice.

Examples:

2 Unfortunately,

DHS~s regulations, at 8 C.F.R. 239.1, do not include OPLA's attorneys among the 38

categories of persons given authority there to issue NTAs and thus to cancel NTAs. That being said,

when an OPLA attorney encounters an NTA that lacks merit or evidence, he or she should apprise the

issuing entity of the deficiency and ask that the entity cure the deficiency as a condition ofOPLA's

going forward with the case. If the NTA has already been filed with the immigration court, the OPLA

attorney should attempt to correct it by filing a form 1-261, or, if that will not correct the problem,

should move to dismiss proceedings without prejudice. We must be sensitive, particularly given our

need to prioritize our national security and criminal alien cases, to whether prosecuting a particular case

has little law enforcement value to the cost and time required. Although we lack the authority to sua

sponte cancel NTAs, we can move to dismiss proceedings for the many reasons outlined in 8 CFR §

239.2(a) and 8 CFR § 1239.2(c). Moreover, since OPLA attorneys do not have independent authority

to grant deferred action status, stays of removal, parole, etc., once we have concluded that an alien

should not be subjected to relTIoval, we must still engage the client entity to "defer" the action, issue the

stay or initiate administrative removal.

2010FOIA4519.000016

All OPLA Chief Counsel

Page 6 of9

• Relief Otherwise Available- We should consider moving to dismiss

proceedings without prejudice where it appears in the discretion of the OPLA

attorney that relief in the form of adjustment of status appears clearly approvable

based on an approvable 1-130 or 1-140 and appropriate for adjudication by CIS. See

October 6, 2005 Memorandum from Principal Legal Advisor Bill Howard, supra.

Such action may also be appropriate in the special rule cancellation NACARA

context. We should also consider remanding a case to permit an alien to pursue

3

naturalization. This allows the alien to pursue the matter with CIS, the DRS entity

with the principal responsibility for adjudication of ilnmigration benefits, rather than

to take time from the overburdened immigration court dockets that could be

expended on removal issues.

• Appealing Humanitarian Factors- Some cases involve sympathetic

humanitarian circumstances that rise to such a level as to cry for an exercise of

prosecutorial discretion. Examples of this, as noted above, include where the alien

has a citizen child with a serious medical condition or disability or where the alien

or a close family member is undergoing treatment for a potentially life threatening

disease. OPLA attorneys should consider these matters to determine whether an

alternative disposition is possible and appropriate. Proceedings can be reinstituted

when the situation changes. Of course, if the situation is expected to be of relatively

short duration, the Chief Counsel Office should balance the benefit to the

Government to be obtained by terminating the proceedings as opposed to

administratively closing proceedings or asking DRO to stay removal after entry of

an order.

• Law Enforcement Assets/CIs- There are often situations where federal, State or

local law enforcement entities desire to have an alien remain in the United States for

a period of tin1e to assist with investigation or to testify at trial. Moving to dismiss a

case to permit a grant of deferred action may be an appropriate result in these

circumstances. Some offices may prefer to administratively close these cases, which

gives the alien the benefit of remaining and law enforcement the option of

calendaring proceedings at any time. This may result in more control by law

enforcement and enhanced cooperation by the alien. A third option is a stay.

4) Post-Hearing Actions:

Post-hearing actions often involve a great deal of discretion. This includes a

decision to file an appeal, what issues to appeal, how to respond to an alien's appeal,

whether to seek a stay of a decision or whether to join a nl0tion to reopen. OPLA

Once in proceedings, this typically will occur only where the alien has shown prima facie eligibility

for naturalization and that his or her case involves exceptionally appealing or humanitarian factors. 8

CFR §§1239.1

1239.1 (t). It is improper for an immigration judge to terminate proceedings absent an affirmative

communication from DHS that the alien would be eligible for naturalization but for the pendency of the

deportation proceeding. Matter of Cruz, 15 I&N Dec. 236 (BIA 1975); see Nolan v. Holmes, 334 F.3d

189 (2d Cir. 2003) (Second Circuit upholds BIA's reliance on Matter of Cruz when petitioner failed to

establish prima facie eligibility.).

3

2010FOIA4519.000017

All OPLA Chief Counsel

Page 7 of9

attorneys are also responsible for replying to motions to reopen and motions to

reconsider. The interests ofjudicial economy and fairness should guide your actions

in handling these matters.

Examples:

• Remanding to an Immigration Judge or Withdrawing Appeals- Where the

appeal brief filed on behalf of the alien respondent is persuasive, it may be

appropriate for an OPLA attorney to join in that position to the Board, to agree to

remand the case back to the immigration court, or to withdraw a government appeal

and allow the decision to become final.

• Joining in Untimely Motions to Reopen- Where a motion to reopen for

adjustment of status or cancellation of removal is filed on behalf of an alien

with substantial equities, no serious criminal or immigration violations, and

who is legally eligible to be granted that relief except that the motion is

beyond the 90-day limitation contained in 8 C.F.R. § 1003.23, strongly

consider exercising prosecutorial discretion and join in this motion to reopen

to permit the alien to pursue such relief to the immigration court.

• Federal Court Remands to the BIA- Cases filed in the federal courts

present challenging situations. In a habeas case, be very careful to assess the

reasonableness of the government's detention decision and to consult with

our clients at DRO. Where there are potential litigation pitfalls or unusually

sympathetic fact circumstances and where the BIA has the authority to

fashion a remedy, you may want to consider remanding the case to the BIA.

Attachments 1-1 and I provide broad guidance on these matters. Bring

concerns to the attention of the Office of the United States Attorney or the

Office of Imn1igration Litigation, depending upon which entity has

responsibility over the litigation. See generally Attachment F (Memorandum

from OPLA Appellate Counsel, U.S. Attorney Remand Recommendations

(rev. May 10, 2005)); see also Attachment G (Memorandum from Thomas

W. Hussey, Director, Office of Immigration Litigation, U.S. Department of

Justice, Remand of Immigration Cases (Dec. 8, 2004)).

• In absentia orders. Reviewing courts have been very critical of in

absentia orders that, for such things as appearing late for court, deprive aliens

of a full hearing and the ability to pursue relief from removal. This is

especially true where court is still in session and there does not seem to be

any prejudice to either holding or rescheduling the healing for later that day.

These kinds of decisions, while they may be technically correct, undermine

respect for the fairness of the removal process and cause courts to find

reasons to set them aside. These decisions can create adverse precedent in

the federal courts as well as EAJA liability. OPLA counsel should be

mindful of this and, if possible, show a measured degree of flexibility, but

2010FOIA4519.000018

All OPLA Chief Counsel

Page 8 of9

only if convinced that the alien or his or her counsel is not abusing the

removal court process.

5) Final Orders- Stays and Motions to Reopen/Reconsider:

Attorney discretion doesn't cease after a final order. We lTIay be consulted

on whether a stay of removal should be granted. See Attachment B

(Subchapter 20.7). In addition, circumstances nlay develop whether the

proper and just course of action would be to 1nove to reopen the proceeding

for purposes of terminating the NTA.

Exa1nples:

• Ineffective Assistance- An OPLA attorney is presented with a situation where

an alien was deprived of an opportunity to pursue relief, due to incompetent counsel,

where a grant of such relief could reasonably be anticipated. It would be

appropriate, assuming compliance with Matter of Lozada, to join in or not oppose

motions to reconsider to allow the relief applications to be filed.

• Witnesses Needed, Recommend a Stay- State law enforcetTIent authorities need

an alien as a witness in a tnajor criminal case. The alien has a final order and will

be removed from the United States before trial can take place. OPLA counsel may

recommend that a stay of removal be granted and this alien be released on an order

of supervision.

**********

Prosecutorial discretion is a very significant tool that sometimes enables you to deal

with the difficult, complex and contradictory provisions of the immigration laws and

cases involving human suffering and hardship. It is clearly DHS policy that national

security violators, human rights abusers, spies, traffickers both in narcotics and people,

sexual predators and other criminals are removal priorities. It is wise to remember that

cases that do not fall within these categories sometimes require that we balance the cost

of an action versus the value of the result. Our reasoned determination in making

prosecutorial discretion decisions can be a significant benefit to the efficiency and

fairness of the removal process.

Official Use Disclaimer:

This memorandum is protected by the Attorney/Client and Attonley Work product privileges

and is for Official Use Only. This Inemorandum is intended solely to provide legal advice to

the Office of the Chief Counsels (OCC) and their staffs regarding the appropriate and lawful

exercise of prosecutorial discretion, which wiUlead to the efficient nlanagement of resources.

It is not intended to, does not, and may not be relied upon to create or confer any right(s) or

benefit(s), substantive or procedural, enforceable at law by any individual or other party in

2010FOIA4519.000019

All DPLA Chief Counsel

Page 9 of9

removal proceedings, in litigation with the United States, or in any other form or manner.

Discretionary decisions of the DCC regarding the exercise of prosecutorial discretion under

this memorandum are final and not subject to legal review or recourse. Finally this internal

guidance does not have the force of law, or ofa Department of Homeland Security Directive.

2010FOIA4519.000020

ATTACHMENT A

2010FOIA4519.000021

0llicc OJ'f):'kJllWII

o//): 'kJllWII lIlId N"lIIlil'lll 0l't'I"tlli,

U.S. DC(l:ll'tnwllt or lIollJcland

I SlrC:CI. NW

Wa~hillgl{ln. DC 205:H,

Wa~hillgl{ln.

Jj}\

Jj}\

Se('urit~

Se('urit~

~125

u. S. Immigration

and Customs

Enforcement

Fiil!C

i

t\1Erv10RANDUlVl FOR:

All

0'

C

wes«~,

MAY 18 ID05

FR01V1:

c' 19 irector

Office ofDct ion and Removal

SUBJECT:

Alien Witnesscs and Informants Pending Removal

PUl])ose

The Office of Detention and Removal Opcrations (DRO), in consultation with the Office of

Investigations (01) and the Office of the Principle Legal Advisor, is issuing this guidance for cases

of aliens pending removal from the United States for whom there is an interest frolll another law

enforcement agency (LEA). The interest may be for any of the following:

o

o

o

An alien on behalf of which an application for an S-visa has been filed by a federal or state

LEA;

An alien for whom thc Department of Justice (DOJ), Office of Enforcement Operations

(OEO) has indicated possible placement in the Witness Protection Program;

For usc of the alien as an informant hy another LEA.

Discussion

Frequently, DRO field offices receive requests from LEAs to stay the removal of an alien who may

be needed as an infonnant or a witness in a criminal matter. The majority of these cases involve

aliens who have becn convicted of serious crimes and are subj cct to mandatory detention. As the

mission of ORO is to remove aliens and detention is uscd for the purpose of crrecting removal, the

liability for not removing aliens for which a travel document is available rests with ORO. ]n

addition, ORO must follo\v congressional mandates and statutes to remove criminal aliens. As such,

DRO will seek to obtain a removal order for all categories of aliens mentioned in this memorandum

prior to any release or transfer of custody to another agency. The possibility of issuing a stay of

removal or deferred action may bc considered only when compelling rcasons exist. Cases of

Limited Official Use

2010FOIA4519.000022

Alien Witnesses and Informants Pending Removal

Page 2

detained aliens for which removal is not foreseeable arc to be handled under the established Post

Order Custody Review procedures. Disposition of aliens who have not heen 11 laced in removal

proceedings will be made by 01 based on the specifics of the case.

Effective immediately, the below procedures are to be followed by all field offices in these types of

cases:

Aliens Pending an 'S' Visa

Federal and state LEAs may request an S-visa on behalf of an alien through DOJ/OEO, when there is

a need [or infonnation provided by the alien witness or inf01mant in criminal or counter-terrorism

matters. Before the application is sent to OEO, it requires the approval of the local United States

Attomey, as well as the headqu31ters of the LEA. Once the application is certified by OEO, it is sent

to ICE for a final dccision pursuant to 8 CFR § 214.2(t). When HQOI is notified of the filing of an

S-visa for a particular alien, HQOI will issue written notification to HQDRO and coordinate the

issuance of deferred action for the alien. If the alien is detained, HQDRO will coordinate the

transfer of custody of the alien to the appropriate LEA v·,..ith the local Field Office Director. The

LEA is to sign receipt orthe alien. The LEA filing the S-visa application will assume responsibility

[or the alien while the alien remains in the United States and is required to provide periodic reports

to HQOI as to the whereabouts and activities of the alien.

Aliens Authorized for the

~VitJ1ess Securitl'

Program by OEO

Aliens may be granted relocation services or some form of "limited services" by DOJ/OEO. One

slich limited service may be ifOEO considers that the alien's life l11ay be in danger outside the

United States. Once OEO provides written notification to DRO that the alien has been approved for

the \\Fitness Security Program under 18 USC 3521, OEO will identify the LEA who will be picking

up the individual fro111 DRO custody, if the alien is detained. ORO will cnsure that custody of the

individual is transferred to the LEA at a pre-arranged time. The LEA is to sign receipt of and

assume full responsibility for the alien. HQOI will coordinate with HQDRO for the issuance of

deferred action hy HQOl. The LEA will provide periodic reports to HQOl as to the whereabouts

and activities of the alien.

In cases where no LEA is willing to assume clIstody of the al iell, and the alien has been ordered

removed, HQDRO will make a final determination regarding execution of the removal order and

advise the local field office. OEO's request not to remove in and of itself may not be sufficient to

postpone or cancel the removal. HQDRO will notify OEO two weeks prior to any anticipated

removal of the alien. If OEO or an LEA requires the presence of an alien who WllS removed from

the United States, they may request that the alien be paroled back into the United States undcr INA §

212(d)(5). This may be accomplished by the LEA coordinating with the Office of International

Affairs, Parole and Humanitarian Assistance Branch.

Limited Official Usc

2010FOIA4519.000023

Alien Witnesses and Infonnants Pending Removal

Page 3

Other Detained Alien Informants

For any other alien for whom an LEA is seeking to use an infoo11al1t, usually for a temporary timeperiod, a leller from the appropriate LEA headquarters management official to HQDRO is required.

The letter must address the following: specific reasons for the request to postpone the removal,

timeframe for which the alien will be needed, that the LEA ngrees to take custody of and be

responsible for the alien, and that the LEA will retuol the alien to DRO at the conclusion of the

timeframe noted on the request. Once this infonnation is provided, the final decision will be

coordinated between HQDRO, HQOI, and local DRO. If the request is approved, the LEA is to sign

receipt of and assume full responsibility for the alien. HQOI will coordinate the issuance of a

deferred action notice and will be provided periodic reports as to the whereabouts and activities of

the alien from the LEA.

Conclusion

The disposition of informants and \'v'itness cases pending removal are to he coordinated closely with

HQDRO. As soon as the local field office is notified regarding an interest in the alien from another

agency, HQDRO is to be notified. HQDRO will also work closely with HQOI in order to protect the

interests of ICE. DRO offices are to ensure that the appropriate documentation involving the

transfer Ofcllstody is maintained in the alien's A-file. It is important that DRO offices ensure that

files, DACS records, and documentation from OEO or other LEAs in such cases are properly

safeguarded, as they are law enforcement sensitive.

Any questions may be addressed to John Tsoukaris or Todd Thurlow, HQDRO Custody

Determination Unit.

Limited Official Use

2010FOIA4519.000024

ATTACHMENT B

2010FOIA4519.000025

INS#ddm-chapter20-46-7

Page 1 of 13

onlinei~1oIS

online~we

INSERTS PLUS/Detention and Deportation Officer's Field Manual/Detention and Deportation Officer's Field Manual/Chapter 21

Process: Relief From Removal

Chapter 20: Removal Process: Relief From Removal

Relief From Removal

Cancellation of Removal

Asylum

Withholding or Deferral of Removal

Private Bills

Restoration or Adjustment of Status and Waivers

Stays of Removal

Deferred Action

Exercise of Discretion

Temporary Protected Status vs.

V5. Deferred Enforced Departure

Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act (NACARA) and Haitial

Immigration Fairness Act (HRIFA)

Voluntary Departure

20.12

20.1

20.2

20.3

20.4

20.5

20.6

20.7

20.8

20.9

20.10

20.11

References:

INA: 101, 208,212,236,

208, 212, 236, 237, 240A, 241, 242, 244,245, 248, 249

Regulations: 8 CFR 10

RegUlations:

03.43, 208, 1240.20, 1240.21, 1240.33, 1240.34, 241.6, 245, 249, 274A

20.1

Rei

Relief

ief from Removal.

Aliens in removal proceedings and those with final orders of removal may be eligible for certain fan

fon

It is important for you to be familiar with these forms of relief because aliens under your docket con

can

eligible. You may be required to cease all removal actions on eligible detained and non-detai

Additionally, certain forms of relief may require the administrative closure of removal proceedi

release of aliens in custody. The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 19

eliminated some forms of relief and created others. You may encounter an alien under docket COl

removal proceedings were initiated prior to the enactment of IIRIRA. Therefore, you must know tl

relief that were available prior to IIRIRA and know what actions each Service officer should take

each particular form of relief.

•

First, consider the alien's immigration status and criminal history before pursuing relief from re

a criminal-history check if you cannot find one conducted during the past 90 days.

The Office of the Principal Legal Adviser reviews the contents of each "A" file before presentir

his

to the Executive Office for Immigration Review. If the file does not contain a current criminal hiE

90 days), the attorney will not proceed with the case and inform you of the incomplete recol

2010FOIA4519.000026

http://onlineplus.uscis.dhs.gov/lpB

http://on Iineplus.uscis.dhs.goy /I pB inplusll

i nplus/l pext.d

pexLdll/Infobase/ddmJddm-l/ddm-1625?f=lem...

11/1 nfobase/ddm/ddm-l/ddm-1625 ?f=tem...

10/24/2005

INS#ddm-chapter20-46-7

Page 2 of 13

then run the required criminal-history check so the Office of the Principal Legal Advisor car

record and proceed with the request for relief.

20.2

Cancellation of Removal.

(a) General. Cancellation of removal is a discretionary form of relief that may be granted to an alier

course of a removal hearing. A detailed description of cancellation of removal may be found at I

and 8 CFR 1240.20. Cancellation of removal applies to aliens placed in removal proceedings a