Usdod Rumsfeld Memo Re Counter Resistance Techniques April 16 2003

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

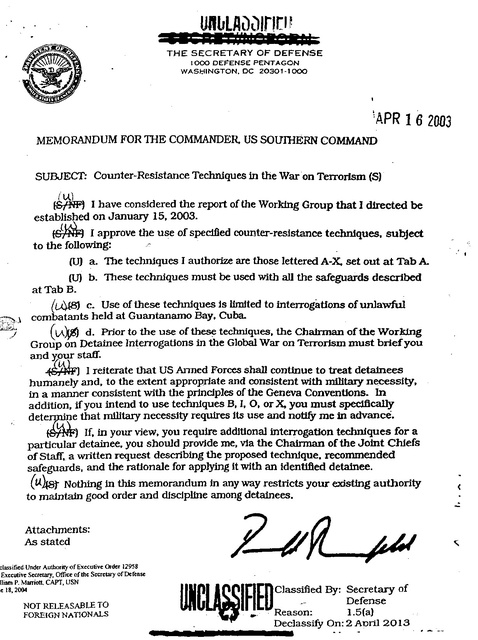

THE SECRETARY OF DEFENSE

1000 DEF'ENSE PENTAGON

WASr.tINGTON. DC 20301-1000

\APR 162003

MEMORANDUM FOR mE COMMANDER. us SOUlliERN COMMAND

SUBJECT: Counter-Resistance Techniques in the War 'on Terrorism (S)

.

)

~ I have considered the report of the Working Group that I directed be

established on January 15. 2003.

~

I approve the use of spec11led counter-resistance techniques. subject

to the following:

/

(V) a. The techniques I authorize are those lettered A-X, set out at Tab A.

(U) b. These techniques must be used With all the safeguards described

at Tab B.

. (uW3J c. Use of these technJques Is limited to interrogations of unlawful

combatants held at Guantanamo Bay. Cuba.

w·~

~-i;;;.,

(LA~ d. Prior to the use of these techniques. the Chairman of the Working

j

Group on Detainee Interrogations in the Global War on Terrorism must briefyou

and your staff.

~) I reiterate that US Anned Forces shall continue to treat detainees

humanely and. to the extent appropriate and consistent with militmy necesstty,

in a manner consistent with the principles of the Geneva Conventions. In

addition. if you intend to use techniques B. I. 0. or X, you must specifically

dete~e that military necessity requires its use and notify me in advance.

~) If, in your view, you require additional interrogation teclmiques for a

particular detainee, you should provide me. via the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs

of Staff. a written request describing the proposed technique. recommended

safeguards. and the rationale for applying it with an identified detainee.

(u1st Nothing in this memorandum in any way restricts your existing authority

to maintain good order and discipline among detainees.

Attachments:

As stated

classified Under Authority of Executive Order 12958

Executive Secretary, Office of the Secretary of Defense

lliam P. Marriott, CAPT,USN

Ie 18,2004

NOT RELEASABLE TO

FOREIGN NATJONALS

III1Cl;IFIED lassified By: Secretary of

un

'.

' . , ' Reason:

1.5(a)

..

C.

.

sm.

"~Defense

Declassify On: 2 April 2013

•

.

I

(

-.

"

TAB A

INTERROGATION TECHNIQUES

[(..\)

-(BI/NFl The use of techniques A - X is subject to the general safeguards as

provided below as well as specific implementation guidel1nes to be provided by

the appropriate authortty, Spec1flc implementation guJdance with respect to

techniques A - Q is provided in Army Field Manual 34-52. Further

implementation guidance with respect to techniques R - X will need to be

developed by the appropriate authority. .

.

(~).

.

.'

f9t IN!")

Of the techniques set forth below. the polley aspects of certain

techmques should be considered to the extent those polley aspects retJect the

views of other major U.S. partner nations. Where applicable. the descnption of

the technique is annotated to include a summary of the poHcy Lssuc:s that

ShOU~)'be considered before apphcanon of the technique.

.'.

A.

'""'\

-

-~

/

l\

~

~

Directf Asking straightforward questions.

.'

B.

incentive/Removal of incentive: ProvIding a reward or removing a

privilege, above and beyond those that are required by the Geneva Convention.

from detainees. ICaution: Other nations that believe that detamees are enUUed

to POW protectionsmay consider that provision and retention ofrel1glous items

(e.g.. the Koran) are protected under international Jaw (see. Geneva 10. Article

34). Although the provisions of the Geneva Convention are not applicable to the

interrogation of unlawful combatants. constderatson should be given to' these

views prior to application of the technique.)

(LA)

.

.'

C~ f&H.Np) Emotional Love: Playing on the love a detainee has for an

Individual or group.

,(r~

D.

Emotional Hate: Playing on the hatred a detalnee has for an

individual or group.

.

(lA\

.

E. ~J INF) Fear Up Harsh:' Slgn1ficantly Increasing the fear level in a detainee.

(~)

. F. tslINF) Fear Up Mild: Moderately increastng the fear level in a detainee.

CIA) ,

.

'

G. fSI/NFl Reduced Fear: Reducing the fear level m a detainee.

(U)

H.

f-St-tNPJ

,

Pride and Ego. Up: Boosting the ego of a detainee.

Classified By:

Reason:

Declassify On:

NOT RELEASABLE TO

FOREIGN NATIONALS

secretary of Defense

1.5(a)

2 Apr1l2013

Tab A

t

(L{\

.

.

L ~ Pride and Ego Down: Attacking or insulting the ego of a detainee,

not beyond the limits that would apply to a POW. [Caution: Article 17 of

Geneva ill provides, "Prisoners of war who refuse to answer may not be.

threatened, insulted, or exposed to any unpleasant or disadvantageous.

treatment of any kind." Other nations that believe. that detainees are entitled to

POW protections may consider this technique inconsistent with the provisions

of Geneva. Although the provisions of Geneva are not applicable to the

interrogation of unlawful combatants, consideration should be given to these

views prior to application· of the technique.)

J.

~~}NPl

Futility: Invoking the feeling of futility of a detainee.

(tA)

...

.

K. t9f'tNP) We Know AD: Convincing the detainee that the interrogator knows

the answer to questions he asks the detainee.

..

~

L.

Establish Your Identity: Convincing the detainee that.the

interrogator has mistaken the detainee for someone else.

~

CO~tinUOUs1Y

M.

Repetition Approach:

repeating the same question to

the detainee within interrogation periods of normal duration.

-

(u)

-

..

. -

-

N.· fBI/NFl File and Dossier: Con~cingdetainee that the interrogator has a .

damning and inaccurate file, which must be fixed.

J/I~

o.

Mutt and Jeff: A team consisting ofa friendly and harsh

interrogator. The harsh interrogator might employ the Pride and Ego Down .

technique. (Caution: Other nations that believe that POW protections apply to

detainees may view this technique as inconsistent with Geneva m. Article 13

which provides that PaWs must be protected against acts of intimidation.

Although the provisions of

are not applicable to the interrogation of

unlawful combatants, consideration should be given to these views prior to

application of the technique.)

Geneva.

~

P.

Rapid F1re: Questioning in rapid succession without &Bowing

detainee to answer.

Q.

(JI/~

Silence: Staring at the detainee to encourage discomfort.

(~.

.

R. fSI/NP) Change of Scenery Up: Removing the detainee from the standard

interrogation setting (generally to a location more pleasant, but no worse).

(~)

..

. .

S. fSffNF)- Change of Scenery Down: Removmg the detainee from the standard

interrogation setting and placing him in a setting that may be less comfortable;

would not constitute a substantial change in environmental quality.

tS~/~

T.

Dletary Manipulation: Changing the diet of a detainee; no intended

deprivation of food or water; no adverse medical or cultural effect and without

intent to deprive subject of food or water, e.g., hot rations to MREs..

2

Tab A

(L-l)

U. (8//N¥) Environmental Manipulation: Altering the environment to create

moderate discomfort (e.g., ac:ljusting temperature or introducing an unpleasant

smell). Conditions would not be such that they would injure the detainee.

Detainee would be accompanied by interrogator at aU times. [Caution:· Based

on court cases in other countries, some nations may view application of this

technique in certain circumstances to be inhumane. Consideration of these

views should be given prior to use of this technique.]

·(S~t~P)

V.

Sleep Adjustment: AdjUSting" the sleeping times of the detainee

(e.g., reversing sleep cycles from night to day.) This technique is NOT sleep

deprivation.

.

_

(S~/Jp"

W.

False Flag: Convincing the detainee that individuals from a

country other than the United States are interrogating him.

(u ) .

- -

x. ~ Isolation: Isolating the detainee from other detainees while still

complying with basic standards of treatment. [Caution: -The use of isolation as

an interrogation techfdque requires detailed implementation instructions,

including ~cific guidelines regarding the length of isolation, medical and _

psychologicel review, and approVal for extensions of the length of isolation by

the appropriate level in the chain of command. This technique is not known to

have been generally used for interrogation purpoSes for lonser than 30 days.

Those nations that believe detainees are subject to POW protections may view

use of this technique as inConsistent with the requirements of Geneva m,

Article 13 which provides that roWs must be protected against acta of

intimidation; Article 14 Which provides that pow. are entitled to respect for

their person; Article 34 which prohibits coercion and Article 126 which ensures

access and basic standards of treatment. Although the provisions of Geneva

are not applicable. to the intC2:'Togalion of unlawful combatants, consideration

should be given to these views prior to application ·of the technique.]

UNelASSIFlfD

-

Tab A

TABS

t». '\

GENERAL SAFEGUARDS

. ..

I

.

..

~ Application of these interrogation techniques is subject to the folloWing

general safeguards: (1) limJted to use only at strategic 1nterrogatlon facilities; (u)

there tsa good basts to believe that the detainee possesses cr1Uca1 JnteDtgence;

(ill) the detainee is medically and operationally evaluated as suttable

(considering all techniques to be used in combination); (IV) interrogators are

speC1fically trained for the techruquets): (v) a sped1lc interrogation plan

(including reasonable safeguards. l1m1ts on duration. intervals between

applications, termination cnterta and the presence or avaiJab1llty of qual1fted

medical personnel) has been developed: (Vi) there Is appropriate supervisson,

and, (VU) there IS appropriate spedfied senior approval for use With any spec11ic

detainee (after considering the foregOing and receiving legal advice).

(U) The purpose of alfinterviews andinterrogatlons is to get the most

infonnation from a detainee with the least intrusive method. always applied In a

humane and lawful manner with sufficient oversight by trained Investigators or

interrogators. Operating instructions must be developed based on command

policies to insure uniform. careful. and safe application of any 1n.terrogauons of

de~ees.

.

( L.L\

.fSIIN~

Interrogations must always be planned. deliberate actions that take

mto account numerous, often interlocking (actors such as a detainee's current

and past performance In both detennon and interrogation. a detaJnee's .

emotlonal and physical strengths and weaknesses. an assessment of possible .

approaches that may work on a certain detaJnee in an eJfort to gam the trust of

the detainee, strengths and weaknesses of interrogators. and augmentatlon by

other personnel for a certain detainee based on other factors.

~

approach~

Interrogatlon

are desJgned to manipulate the detainee's

emotions and weaknesses to gain his W1ll1ng cooperation. lnterrogatton

operations are never conducted In a vacuum; they are conducted in close

cooperation with the units detaining the Indrvtduals, The policies establtshed

by the detaining units that pertain to searching. silencing. and segregattng also

playa role 10 the interroganon of a detainee. Detainee interrogation involves

developing a plan tailored to an 1Ddtv1dual and approved by senior

Interrogators. Stnct adherence to pohctes /etandard operating procedures

governing the administration of interrogation techniques and oversight is

essential. .

Class1fied By:

NOT RELEASABLE TO

FOREIGN NATIONALS

Secretary of Defense

Reason:

1.5(~)

Declassify On:

2 April 2013

TabB

UNClASSIHtu

..

~~

IINp) It is important that interrogators be provided reasonable latitude to

.

vary techniques depending on the detainee's culture. strengths. weaknesses.

environment. extent of training in resistance techniques as well as the urgency

of obtaining information that the detainee is mown to have.

.

~

While techniques are considered individually within this analysis, it

must be understood that in practice, techniques are usually used in

combination; the cumulative effect of all techniques to be employed must be

considered before any decisions are made regarding approval for particular .

situations. The title of a particular technique is not always fully descriptive of a

particular technique. With respect to the employment of any tecl>niquea

involving physical contact. stress or that could produce physical pain or harm,

a detailed explenaticn of that technique must be provided to the deciaion

.

authority prior to any decision.

VNCJjSS/FiED

TabB

,.:\'

:;',,\

FM 34·52

» ;

\

TIme permmtng, each interrogator should UDobtrusively observe the source to personally confirm his

identity and to check his personal appearance and behavior.

After the interrogator bas collected aU information

available about his assigned source, he analyzes it. He

looks for indicators of psychological or physical weakness that might make the source susceptible to one or

more approaches, .,..,hicb tadUtates his approach

strategy. He also uses the information he collected to

identify the type and level _of knowledge possessed by

the source pertinent to the element's collection mission.

• Combat effectiveness.

• Loglsncs,

• Electronic technical data.

• Miscellaneous.

As a result of the planning and preparation phase, the

interrogator develops a plan for CODdu~tiDg his usiped

interrogation. He must review this plan with the senior

interrogator, when possible. Whether written or oral,

the interrogation plan must contain at least the foU01lll·

ing items:

• Primary and alternate approaches.

The major topics that can be covered in an imerrogation are shown below in their normal sequence. How.

ever, the interrogator is free to modify this sequence a.o;

• Questioning techniques to be used or Why the interrogator selected only specific topics from the

basic questioning sequence,

.)

'/

-

• EPW's or detainee's identity, to inc:lude wual ob.

servauon of the EPW or detainee by the taterrogator.

.I.

"

'

• Interrogation tUne and place,

• Means C!f recording and reponing information ob.

lained.

• Missions.

The senior interrogator reviews each plan and makes

any changes he feels necessary based OD the

commander's PIR and IR. After the plan is approved,

the holding compound is notified when to bring tbe

source to the interrogation site. The interrogator col.

lects all available interrogation aids needed (maps,

charts, writing tools, - and reference materials) and

proceeds to the interrogation site.

• Composition.

• Weapons, equipment, strength.

• Dispositions.

• Tactics.

• Training,

The approach phase begins with initial contact between the EPW or detainee and interrogator. Extreme

care is required since the success or the interrogation

hinges, 10 B large degree, on the early development of

the EPW's or detainee's willingness to communicate,

The interrogator's objective during this phase is to establish EPW or detainee rapport, and to gain his willing

cooperation so he wilJ correctly answer pertinent questions to follow. The interrogaror• Adopts an appropriate attttude based on EPW or

detainee appraisal.

• Prepares for an attitude change, ifneeessary.

I

set

but

APPROACH PHASE

COl!

• Begins to use an approach technique.

The amount of time spent on this phase wiD mostly

depend on (he probable quantity and value or information the EPW or detainee possesses, tbe a'Vailability of

other EPW or detainee with knowledge OD the same

topics. and available lime. At the initial contact, a ; .

businesslike relationship sbould be maintained. As the ·fu

EPW or detainee assumes a cooperative aunude, a -,~.

more relaxed atmosphere may be advantageous. The in. -t,

terrogaror must Qlrefully determine which ot the 'i.

various approach techniques to employ.

Regardless of the type of EPW or detainee and his / ;

outward personality, be does possess 11VCaknCSle5 wIdell, ":j:t

('

:;~"f

3·10

.

i':"

• Interrogation objective.

The interrogator uses his estimate of the type and CI·

lent of knowledge possessed bythe source 10 modify the

basic topical sequence of questioning. He selects only

those topics in ",bieb he believes the source has pertinent knowledge. In this way, the interrogator refines

his element's overall objective into a ~et of specific interrogation subjects.

necessary.

I

I

•

•

•

71

even

cura

teon

JUN-22-2004

DUD GENERHL

11:04

~UUN~tL

FM 34-52

."".

jf. recognized by the interrogator, can be exploited.

These weaknesses are manifesled in personality traU'

:r~~';J SJJch as speech. mannerisms, facial erpresslons, physical

.~:..~:;,;;: .mevemeats, excessive perspiration, and other overt in'T.".:~,'~·:'.:·dicatiOnsthat vary from EPWor detainee.

\~''''

interrogator's questioDSJ not necessarily his cooperation.

)J'::~~7'"

The source mayor may not be aware he is providing

the interrogator with informatioa about etIemy forces.

Some approaches may be CX)mp)e~ wben the source

begins to answer questions. Others may have to be eonstantJy malntalne4 or reinforced throu_hout tbe mterrogation. '

From a psychological standpoint. the interrogator

following behaviors, People

·.l:f'> lend

must be cognizant of the

tot,.:.~,

,¥>:~}~\ .". Talk, especially after harrowing experiences.

,:)''''~I'·).'''.'

t.

•

~'; .:/,~~~;~:.•

;!'

'.

.;~; -:.. .

L~·;·.'~·l

Q ~"~~';::,

.:

:{

-,

Sbow deference when confronted by supenor

authority.

'

,~

:. ~~)~I\):.YI,"

Rationalize acts about which they feel guilty.

•

~ .f~;\i~:~·

Fai) to apply or remember lessons they may have

·t~~( .. been taught regarding s~urily it confronted with a

';r; disorganUed or strange SItuation.

" I

•

C,t;'

•

~. COoperate with those who h>~,ve control over them.

···~:~~tach less importance to a topic about whjclJ the

~hnteJTogator demonstrates identical or related esi~rience or lcnowleC2ge.

1'\.: ppreciate flattery and exoneration from gUUt.

,,' "ent having someone or something they respect

~'t~~ed, especially by someone tbey dislike.

_.~1ond to kindness and understanding during

· g circumstances.

j~

'-:

·.perate readily when given material rewards

~~as extra food or lUXUry items for their

per-

. ~lc:omforL

t,

,

. ; ,tors do not "run" an approach by following a

• ':or routine. Each interrogation is different J

wogation approaches have the following in

J

m~

,

.

".,-"

'1'~:~~b and

'r

..... \

."

tion,

maintain control over the source and

The techniques used in an approa~h can best be

defined as a series of events, not just verbal conversetion between the interrogator and the source. The Qploitation of the source's emotion can be barsh or

gentle in application. Some useful techniques used by

interrogators are-• Hand and body movem.ents.

• ActUal physic:al contact such as a hand on the

shoulder tOf reassurance.

• Silence.

RAPPORT POSTU~ES

There are two types of rapport postures determined

dUring planning and prepantioD: stern and sym.

pathetic.

In [he stem po6lure, the interrogator keeps the EPW

or detainee at attemion. The aim is to make the EPW

or detainee keenly aware

his belpless and inferior

status. Interrogarors we tbis posture whh officers,

or

NCOs. andsecurity-conscieus enlisted men.

In the sympathetic POSlUJe J tbe interrogator addresses

the EPW or deudnee in a friendly fasbJon. striving to

put him at ease, This posture is commonly used in interrogating older or younger EPWs. EPWs may be

frightened and confused. One variation of this posture

is "'heD rheInterrogator uks about tbe EPWs family.

Few EPWs will hesftate to discuss meir family.

Frightened persons, regardless of rank, will invariably

talk in order to relieve tension once they bear a sympathetic voice in their own tongue. To put the EPWat

ease, the interrogator may allow the EPW to sit down,

offer a cigarette, ask wbether or not he needJ medical

care, and otherwtse show interest in JUs case.

There are many variations of these basic posreres,

Regardless of the one used, the interrogator must

present a military appearance and sbow character and

energy. The interrogator must control bis temper at all

times, excepr when a display is planned. The inter-

3-11

.,

"

"

FM 34-52

rogator must not waste lime in pointless discussions or

make promises be cannot keep; for example, the

Interrogator's granting poUtical asylum.

When making promises in 3D etlon (0 establish rapport, great care must be taken to prevent implying that

rights guaranteed the EPW under International and US

law will be withheld if the EPW refuses to cooperate.

Under DO circumstances will the interrogator betray

surprise at anything the EPW might say. Many EPWs

will talk freely if they feel the information they are discussing is already known to tbe interrogator. If the interrogator acts surprised. the EPW may stop talking

immediately.

The interrogator encourages an)' behavior that

deepens rapport and increases the now of communication. At the same time. the interrogator must discourage any behavior that has the opRPsite e(fecL

The interrogator must alwaY$ be in control of the interrogation. I( the EPW or detainee challenges this

control, the interrogator must act qUickly and firmly.

Everything the interrogator says and does must be

within 'the limits ofthe GPW, Article 17.

DEVELOPING AAPPOln

Rapport must be maintained throughout the interrogation, not only in the approach phase. If tbe interrogator has established good rappon initially and tben

abandons the effort, the source woukl rigbtfully assume

the interrogator cares less and less about him as the information is being obtained. If this occurs, rapport is

lost and the source may cease answering questions.

Rapport maybe developed I?r• Asking about the circumstances ot capture. By

doing this, the interrogator can gain insight into

the prisoner'S actual state of mind and, more importantly. be can ascertain his possible breaking

points.

• ASking background queSlions. After asking about

the source's circumstances of capture, apparent interest can be buiJr by asking about the source's

family. civilian life, triends, Ukes. and dislikes. This

is to 4evelop rapport, but nonpeninent questions

may open new avenues for tbe approach and help

determine whether tentative approaches chosen in

the planning and preparation phase wiD be effec,.rive. If these questions shOW tbat the tentative appreaches chosen will not be effective, a flexible

3-12

\

,'.

,.

interrogator can r;hift the approacb direction

whhout the source being aware of the change.

Depending on the situation, and requests the source

may have made, the interrogator also can use the following [0 develop rapparL

• Offer realistic: incentives, such as-

-Immediate comfort items (cOffee, cigarettes).

~

-Shon-term (a meal, shower, send a letter home).

,.

-Long-term (repatriatiou, political asylum).

:i

• Feign experience similar to those of the source.

• Show concern for'the source through the use of

voice vitality and body Jangu.age.

• Help the source to rationalize his guilt.

• Show kindness and understanding toward the

source's predicament.

• Exonerate the source from guilt.

• Flatter the source.

Alter h8vin~ established control and rappon, the in-.'

terrogator continually assesses the source to see if the'

approaches-c-and later the questioning techniq'Ues-..'

chosen in the planning and preparation phase 9lill in-.

deedworJc.

.

.

Approaches chosen in plannIng and preparation are'

tentative and based on the sometimes- scanty informa

tion available from documents, guards, and personal ob.:.

servation, This may lead the interrogator to seJect

approaches "-hicb may be totally incorrect for obtainiD '

thJs source's willing cooperation. Thus, careful assess

ment of the source is critical to avoid -"astin, valuabl·.

time in the approach phase.

The questions can be mixed or separate. If. for

ample, tbe interrogator bas tentatively chosen a

I

a

a

t

J

a

n

T

el(

~love

0.

comrades" approach. he should ask the source quesdo .'

like "How did you gel along with your fellow sqU8:,

membersz" If tbe source answers they were all ve:

close and worked well as a team, the interrogator ~:

use this approach and be reasonably sure of its SUcc:l::ss.~·

Ho....ever. if the source answers, "'They all bated

t

iii

~

guts and] couldn't stand any of them; the inlerrogat,~

should abandon that approach and ask some quick. n~:

pertinent questions to give himself time to work out;('j .

new approacb.

.:~.

'Ii"~

·th

inl

je<

In'

the

Im

tht

.1'01

'an

:; ;~i1I

~,~

FM 34-62

r~:t:"

Smooth Transftlons

must guide the conversation

f.: ",~,r;$stDOOlbJy and logically. especially if he needs to move

itw'~fiPm one approacb technique to another. "Poking and

;; ~:"f,>'.·~··I}j'Opin( in (he approach may alen the prisoner to ploys

'~~~n'd will make the job more difficu)l

....

/~

.,jJ;.~:;'I.'.The Interrogator

.,I~"'\

J'.,

},:

<

I~.'·"

': ~ .ltll~{>: TIe-ins

(0 another approach can be made logically

, '":" ~~:;"~.~d smoothly by using transitional phrases. Logical tie\ '/~" ~,;J~ can be made by includiDg simple sentences which

~:i:{;'Connect tbe previously used approach with the basis for

l

/ ':4

~:'-~~be next one.

1.;.,

~~,:

:.;

Transitions an also be smoothly covered by leaving

, ,~rl'f.'i~tbe unsuccessful approach and going back to noaper: :"~X:"inent questions. By using nonpertinent conversaticn,

,: ,~';~~' the interrogator can move the conversadon in the

: ;~1f.:!:;~:,.'~esiIed direction and. as previously stated, sometimes

:' :~:~fSt;can obtain Jeacl& and hints about the source's stresses or

; ""':;~';;;:'weaknesses or other approacbstraregtes that may be

, ... 'r'

"

, :'·~fi7, more successful,

~

.:

~r.l·~':·

·n~~;:

';'~'f.:

:

Slnce,e and Convincing

, ,~,,;,:

" If an interrogator is using argument and reason to 0lIet

~(" ,

,the source to cooperate, he must be convincing and ap"pear sincere. All inferen~ of promises, Situations, and

, arguments, or other invented miilteriaJ must be believ.

:",,: able" What a source mayor may not believe depends on

:: . the interrogator's knowledge, experlence, aod training.

A good source assessment is the basis tor the approach

and vital to the success of the lnrerroganon effort.

>:A;:

:,

J

f

J

I

1

i

I

;

continue to work until he feels the source it near break-

ing.

Reeognlz8 the Breaking Point

Eve.ry source has a breaking poim, but an interrogator never knows what jt js until it has been reacbed.

There are, however, some good indicators the source is

near his breaking point or has already reached iL For

example, if during the approach, the source leaDS forward with his facial expression indicating an interest in

the proposal or is more hesitant in his argument, he js

probably nearing the breaking point The interrogator

must be alert to recognlze these signs.

Once the interrogator determines the source is breaking. be should interject a question pertinent to the objective of the interrogation. If the source answers it, tbe

interrogator can move into the questioning phase. It

the source does nOI answer or balks ar answering it, the

interrogator must realize the source was nOI as cJose to

the breaking pain I as thought, In this case, (he interrogator must continue with hi! approach, or switch to

an alternate approach or questioning technique and

The interrogator can ren it (he source has broken

only by interjecting pertinent qllestioDL TIlis process

must be fol1owed unlit the EPW 6r detainee begins to

answer pertinent questions. It is possible the EPW or

detainee may cooperate for a while and then balk at

answering further questions. U this occurs. the interrogator can reinforce the approathe" thai initially

gained the source's cooperation or move into a difIerenr

approaCh before returning to the questioning phase.

At this point, it is Important to note the amount of

time spent with a particular source depends on several

fadon:

• The banJefield slruation.

• Expediency which the supported commander's PlR

and IR requirements need to be answered.

• Source's willingness to talk,

The number or approaches used is limited only by tbe

Interrogator's sJcill. Almost any ruse or deception is

usable as Jong as the provisions of tbe GPW. as outlined

in Figure 1-4, are not violated.

An interrogator must not pass hhnself off as a medic,

chaplain, or as a member of the Red Cross (Red Qes-

or

cent

Red Lion). To eve.ryapproacb technique, there

arc literally hundreds of possiblevariarions, each of

which can be developed for a specific situation or

source.

The variations are limited only by tbo

interrogator's personality. experience, ingenuity, and

imagination.

APPROACH COMBINATIONS

With the exception of lhe direct approach. no other

approach is effective by itself. Interrogators use different approach tecbniques or combine them into a

cohesive. logical technique. Smootl.l transJlion~, sincerity, logic, and conViction almost al~ys make a

&lralegy work. The Jack of will undoub(edly dooms it to

failure. Some examples of combinations are--

• Direct-futility-incentive.

• Direct-futiJity-)ove of comrades.

• Direct-fear-up (mild}-incen(ive.

1lIe number of combinations are Unlimited. Interrogators must carefully choose the approach strategy in

(he planning and preparation phase and listen carefully

3-13

JUN-22-2004

11:06

DOD GENERAL COUNSt.L

FM 34-52

to what tbe source is sayillg (verbally or nonverbally) for

leads the strategy chosen will bot work. When this occurs, the interrogator must adapt to approaches he

believes wilJ work ib gaining the source's cooperation.

The approach technlques are not new nor are all tbe

possible or acceptable techDiquC8 discussed belo ....

Everything the interrogator says and does must be in

concert with tbe GWS, GPW, Gc, and UeMJ. The approaches which have proven effective are-e• Direct.

• Incentive.

• Emotional.

• Increased fear-up.

• Pride and ego.

Dlred Appro8ch ;:::.

The interrog81or-asks questions directly related to information sougbt, making no effort to conceal the

interrogation's purpose. The dira;t approach, always

the first to be anempted, is IJsed on EPWs or detainees

who the interrogator believC8 will cooperate.

This may occur when interrogating an EPW or

detainee who bas proven cooperative during inilial

screening or fiJ$t interrogation. Ir may also be used On

those with little Or no security uainlng. The direct approach works best on lower enlisted personnel, as tbey

have little or no resistance training and bave had minimal security training.·

The direct approach is simple to use, and i( is posslble

to obtain the maximum amount of information in tbe

minimum amount of time. II is frequently employed a(

lower echelons when the tscucal situation precludes

selecting other techniques, and where lbe EI'W's or

detainee's mental state is one of confusion or extreme

shock. Figure C3 contains sample questions used in

direct questioning.

The direct approach is the most effective. StatistiC3

show in World War II, it was 90 percent effective. In

Vietnam and OPERATIONS URGENT FURY, JUST

CAUSE, and DESERT STORM, it was 95 percent effective.

Incentive Approach

The incentive approach is based on the applic:ation at

inferred discomfort upon an EPW or detainee who lacb

IL'iJIpower. The EPW or detainee may display (ondness

for cenain IUXllty items such as candy, fruit. or cigarettes. This fondness provides the interrogator with a posi·

live means of rewarding the EPW or detainee for

cooperation and trutbfulness. as he may give or withhold sucb comfort Jtcms at his discretion. Caution must

be used when employing this technique beca~

52

si

e. Any pressure applied in this manner must Dot

amount to a denial ot basic human needs under

any circumstances. (NOTE: lJ'Ilerrogatol$. may not

Withhold a soura:', rights under tbe GPW, but

they can wilhlJoJd a source's privileges.] Granting

incentives must not infringe on these righlS, but·

they caD be things to which the source is already

entitled. This can be effective only if the source is

unaware of his rights or privileges.

wi

.TI

tb

m.

.ot

th

de

co

• The EPW or detainee might be templed to provide

false or inaccurate information to gain the desired

luxury item or to &top the interrogation,

an·

ITe

The GPW, Article 41, reqUires the posting of the convention contents in the EPW's own language, This 15 an

po

un

tht

MP responsibility.

Incentives must seem to be logical and possible. An

interrogator must not promise anything lhat cannot be

delivered. Interrogators do not make promises, but

usually infer them while sidestepping guarantees.

For eu.mple, it an interrogator made a promise he

could not keep and he or another interrogator had to

talk witb the source again, the source would not have

any trust and would probably not cooperate. Instead or

clearly promising a certain thing, such as political

asylum, an interrogator 9o'lU offer to do what he can to

help achieve the source's desired goa); as long as the

source cooperates.

As with developing rapport. the incentive approach

can be broken down into two inl:entives. The determination rests on wben the source expects (0 receive the

incentive offered.

at

'

lUr

1

apf

on

ces

dir'

ob;

rog

do'

cba

7

end

rogr

erne

• Short term-s-recelved immediately; for example,

letter home,seeing wounded buddies.

• Long term-received 'tIIlthin a period

example, political asylum.

pre

corr

[he:

time, for '.

5i

teml

rnus

Emotlona' Approach

Through EPW or detataee observation, the inter- .{

rogator caD often jd~nliIy dominant emotions \IIhich

motivate. The mot~tb1g emotion may be greed. love, ~':

bate, revenge, or others, The interrogator employs ver-

t

i·

.t,~

~. ,

1-14

b

E

obje

emo

If

for t

JUN-22-2004

11:07

DOD GENERHL CUUNScL

:; ~.::}.~)"

FM 34-52

.: ..~ t;fJ<·

.

('~"r""'" ,

:\. ";::;;:;'.1, and emotional ruses in applying pressure to tbe

~11$.:pw's or detainee's dominant emotions.

;~:

'::.! . ~~;~j~;.one major advantage of this technique is it is ver:f:: .2'~~t~iie .and all?~ the interro~a[or to use the same basic

';: ~'"~~ttUJItIOD positively and negslJvely.

;' .f'

'Por example, this technique can be used on the EPW

*~i:'~~~ has a great love for his unit and fell~w soldi~rs.

;:'

;:~'~e

,

interrogator may take advantage of thIS by telling

. );;if:1:~U;e EPW that by providing pertinent information, he

'~/ !j£i·~,may. shorten the war or battle in progress and save many

:~ :::;y~;X~~f' his comrades' lives, but hiS refusal to 1.81k may cause

: '.Ii~~\;~~eir deaths. This places file burden on the EPW or

" ,:, . ~~tZ!;aiLainee and may motivate him to seek relief through

t

,{/~:t.\

I

•

•

•

.: . ~!!Y~/cooperanon.

"~ !>{hr,.~

..'. ~1i(·

.

Conversely, (his technique can also be used on the

.: ;. (~~~.):$PW or detainee who bates h~ unlt because it withdrew

: '\~it'~nd left him to be captured, or who feels be was unfairJy

.':::;·:!'treated in his unit. In such cases; the interrogator can

~: ..point out that if the EPW cooperates and specifies the

:;\: unit'S location, the unit can be destroyed, tbus giving

.:f.?thC EPW an opportunity for revenge. The interrogator

,:'::;;. proceeds \lIith this method in a very formal manner.

.~J.\f II

.•.~' :.

." i·

I

This approach is likely to be effective with the imIna-

lure and timid EPW.

.<"" Emotional Loy~ Approacb. For the emotional love

. , approach to be successful, tbe interrogator must focus

on the anxiety felt by the source about lhe circumstuces in which be finds himself. The Interrogator must

direct the Jove the source feels toward the appropriate

object: family, homeland, or comrades. If the interrogator can show the source what the source himself caD

do to alter or improve his situation, the approach has a

chance of success,

1

t

f

1

!

!

\

ThiS approach usually Invoives some incentive such as

communication with the source's family or a quicker

end to the war to save his comrades' lives. A good interrogator will usually orchestrate some futility with an

emotional love approach to hasten the source's reaching

the breaking point,

Sincerity and conviction are critical in a successful atlove approach as the Interrogator

must show genuine concern for the source, and for the

Object at which the interrogator is direcling the source's

emotion.

tempt at an emotional

If the interrogator ascertains lhe source has great love

for his unit and fellow soldiers, the Interrogator can

er·

i

f

!

I

L

fectively exploit tbe 5ituation. This places a burden OD

the source and may motivate him to seek relief through

cooperation with tbe interrogator.

Emotional Hate ~proacb. Thet emotional bate approach focuses on any genuine hate"or possibly a deslre

for revenge, the source may ted. Thb interrogator must

ascertain exactly what it is the source may bate so the

emotion can be exploited to O'Ierride the source's ratioDal side. The source may have negative feelings

about ~ country's regime, immediate superiors, of.

ficers in general, or reuow soldiers.

This approach is usually most effective on members

of racial or religious minorities who have suffered dis.

crimination in mllitaJ}' and civilian life. H a source feels

he bas been treated unfairly i1I his unit, the interrogator

can point out tbat, it the source cooperates and dtvulges

the location ot tbat unit, the unit can be destroyed, thus

affording the source revenge.

By using a conspJraloriaJ tone of voice, the interrogator can enhance the value of this technique.

Phrases, such as "You owe them

loyalty for the wfl'J

they treated you,~ when used appropriately, can expedite

tbe success of this technique.

no

Do not immediately begi .. to berate a certain facet of

the source', background or lite unti! your assessmene ladicates the source feels a negative emotion toward it.

The emotional hate approach can be lUed more effectively by drawing out tbe soeree's negative emotioDS

with questions that elicit a tbought-provoldng response.

For example, "Why do you think they allowed you to be

captured?" or "Why do you think tbey left you to die?"

Do not berate the source's forces or homeland unless

certain negative emotions surface.

Many sources may have great Jove for their (Dun ny,

but may bate the regime in control. The emotional bate

approach is most errecti~ witb the immature or timid

source who may have no opportunity up to tbJs point

for revenge, or never hael the courage (0 voice his feeling$.

Fe.r-Up Approach

The fear-up approach is the exploitation of 8 source's

preexisting fear during the period of capture and Interrogation. The approach works best willi young, inexpenenced sources, or sources who exhibit a greater than

normal amount of fear or nervousness. A source's fear

may be justiJied OT unjustified. Por example, a source

who bas tommiuecl a war crime may justifiably fear

3-15

JUN-22-2004

11:07

UUU

u~NCKHL

~UUN~CL

...

..,.

FM 34·52

prosecution al14 punisbmenL By contrast, a source who

has been indoctrinated by enemy propaganda may unjustifiably fear that be will suffer torture or death in our

hands if captured.

This approach bas the greatest potential· to violate

(he law of war. Great care must be taken to avoid

threatening or coercing a source which is in violation of

the GPW, Article 17.

It is critical tbe interrogator distinguish what the

Source fears in order to exploit that fear. The way in

which the interrogator exploilS the source's fear

depends on whether tbe source's fear is justified Dr unjustified.

Fear-Up (Harsb). In this approach. [he Interrogator

behaves in an overpowering manner, with a lOUd and

threatening voice. The interrogator may even feel the

need to throw Objects across the room t(t'-'beighten the

source's implanted feelings of fear. Great care must be

taken when doing this so any acrions would not violate

the prohibition on coercion and threats containe4 in the

GPW. Article 17.

This technique is to convince tbe source be does in-

deed have something to fear; that he has no option but

to cooperate. A good interrogator will implant in the

source's mind that the interrogator himself is Dot the

object to be feared. but is a possible way out of the trap.

Use the confirmation of fear only on sources whose

fear is justified.. During this approach, confirm to the

SOUTce that he does indeed have a legitimate (ear. Then

convince tbe source that you are the source's best or

only hope in avoiding or mitigating tbe object of his

(ear, such as punishment for his crimes.

You must take great c::are to avoid promising actioDi

that are Dol in your power to grant, For example. if the

source has committed a war crime, intonn the source

that the crime has been reported to the appropriate

authorirles and that action is pendjn,. Next inform the

iource that, if he cooperates and tells the truth, you will

'eport that he cooperated and told the truth to the apircpriare authorities. You may add that you will also

eport his lack of cooperation. You may not promise

hat the charges againsr him will be dismissed because

011 have no authority to d~miss tile charges.

Few.Up (MWU- 'This approach is better suited to tbe

trong, confident typ( of interrogator; there is generally

o"necd to raise the voice or resort to heavy-handed.

lble~banging.

.

., .. .

For example, capture may be I result of coincidenee:--tbe soldier was caught on the wrong side of

the border before hostilities actually commenced (he

was armed. he CDuJd be a terrorist)--or as a result of his

actions (he surrendered contrary to his military oath

and fa now a traitor to his country, and his forces will

tab care of the disciplinat}' action).

The fear-up (mild) approach must be credible.

usually invo~ some logical incentive.

It

-~\

,

.te Ie

enol

Ifthl

usua

n

fear

actio

aJPpl

io.r<

In most cases, a loud voice is not necessary. The ac-

SOliI'

tual [ear is increased by helping the source realize the

unpleasant consequences the factS may cause and by

prc.senting an alternative. which. of course, can be

brought about by answering some simple queslions.

Ie,citi

The fear-up (harsh) approach is usually a dead end.

and a wise interrogator may want to keep it in reserve as

a (rump card. Af:ter working to increase the source's

fear. it would be difficult to convince him everything will

be all right if the approach is not successful.

Fe.r-Down Approach

This technique is nolbing more than calming the

source and convincing him be will be properly and

humanely treated, or teDing him the war for him is mercifully over and ~e' need not go into combat apln.

When used with a soothing, calm tone or voice, this

often creates rapport and .usually nothing else is needed

to get thesource to cooperate.

WhJle calming the source, it is a good idea 10 stay ini~

tlally Witb Donpertinent conversation and to avoid lbe

subject which has caused the source's fear. This works

quickly in developing rappen aDd QDmmunication, as

the source will readily respond to kindness.

When usin, [his approach, it is important the interrogator relate to the source at his perspective level and

DOl expect the source to come up to the interrogator's

leYel.

If the EPW or detainee is so frightened he has

withdrawn into a sheD or regressed to a less threatening

state of mind. the interrogator must break throup to

him. The interrogator can do this by putting himself on

(be same physicallcvel as the source; this may requ!re

some physical cootaa. As the source relaxes and begms

to respond to kindness, the intenogatoT can begin asking

pertinent quesuees,

This approaq. technique may backfire if allowed to

go too far. After a>nvincing the source he has nothing

~OJ

toa

red..

is tbl

direc

bew,

.torrn

n

binCl

sour.

tiall)

his I.

vina

mgc

n

into

ing t

weal

defi(

gl1~

this 1

n

Imp'

souro

Old)

othe

the c

coujl

river

n

ques

tioll·

vindJ

ODe,

DUU

u~N~~HL

~UUN~CL

. !.'., ':<~ ;J~'.'

.:i;~\~),: .:

~i(~u~'

,~

FM 34-52

;:i~~JeaT, be may cease to be afraid and may feel secure

,\\·bugll to resist the interrogators pertinent question.

, ":this occurs, reverting to a harsher approach technique

"ally will bring the desired result quickly_

"~v

:, ,: ~the fear-down approach works best if the source's

~.. \J:·.,~r is unjustified. During this approach, take specific

,~;·~/;~~tions to reduce the source's unjllSutied feat. For ex:1~:~~fPle. if the SOUTce believes that he wiD be abused lVhile

r:~?iJ9. your custody, make extra etIort5 to ~nsure thaI the

is

foT. fed, and appropnately treated.

J,·.2i:W"ce weU cared

l;.;:~.,~:,:,aonce the source is convinced that he has no

:t~;:!~~timate reason to ~ear you, he ~ill be more inclined

·t 2{~6 cooperare. The interrogator IS under no dury to

;: !i';::ieduce a source's unjustified fear. The, oDly prohibition

~ .r,. (~that the interrogator may not say or do anything thin

'.:. ,:~jrectly or indirectly communicates to the source: tbat

, .f!'1te will be harmed unless he provid~ the requested ill:.~1.fformatjon.

"l'r'

u.i\,\'.

:~~(

These appliCiitions of the fear approach may be comFor example. if 8

')sourc.e

has

justified

and

unjustitJed

fears,

you may jnj,;;e

',~1~ti8JIy reduce the source's unfounded rears, then confirm

J:,his legitimate fears. Again, the source sbould be COD.;~,vin~ the interrogator is his b~t or only hope in avoid::; ing or mitiga ling the object of his fear.

.~: bined to achieve the desired effect.

','

Pride and Ego Approach

The strategy of this approach is to trick the source

revealing desired information by goading or flattering him. It is effective with sources who have displayed

~ : weakness or feelings of inferiority. A real or imaginal)'

~

deficiency voiced about the source, loyalty to hiS orf)

gamzation, or any other feature can provide a basis for

this technique.

, intO

,

I

'

II .

I

!

t,

The interrogator accuses tbe source of weakness or

implies be is unable to do a certain thing. This type of

source is also prone to excuses and reasons why be did

OT did DOt do a certain thing, often shJfting Ihe blame to

others. An example is opening the interrogation with

the question, "Why did you surrender so easily when you

could have escaped by crossing the nearby ford in the

river?"

The source is likely to provide a basis for further

questions or to reveal signilianf inteUigence informa~

tion if he attempts to explain his surrender in order to

vindicate himself. He may give an answer such as, "No

one could cross the ford because il is mined,"

This technique can also be employed in another manner-by fianering the source into admitting certain information in order to gain credit Fqr example, while

iDlerrogati~g a suspected saboteur, ,Ihe interrogator

states; "'I'lm \VaS a smooth operation. I have seen many

previous attempts fail. 1 bet you planned Ihis. Who el&e

but a clever person like you would have planned it?

When did you first decide [0 do the job?This tc:ebnique is espeeiaUy effective with the source

who has bun looked down upon by his superiors. The

source has the opportunity 10 show someone be is intelligent.

A problem wilh the pride and ego approach is it relics

on trickery, The source Vo'iII eventuaUy realize he has

bun tricked and may refuse to cooperate funher. If this

occurs, the interrogator can easily move into a fear-up

approach and convince the source the questions he bu

already answered have committed him, and it would be

useless to resist furlber.

The interrogator can mention it will be reponed to

the source's forces that he has cooperated tully witla the

enemy,...m be co~idere4 a traitor, and has much to rear

if he is returned to his forces.

This may even offer the interrogator the option to go

into a love-of-family approach Where the source must

protect his family by preventing hia CoraS from learning

of his duplidry or collaboration. Telling the SOurce you

will nor report that he talked or (bat he was a severe discipline problem i5 an incenli'/e that may enhance the effecti~eness of the apJ)roach.

Pride and flO-Up ApproICb This apprbacb is most

effective on sources with UUle or DO intelligence, or

tbose who bave been looked down upon for a long rime.

II is very effective on low-ranking enlisted personnel

and junior grade officers, as it allows the source to finally show someone be does indeed have some "brains.•

on

The source is constantly Banered Into providiJa. eertain information in order to gain credit The interrogator must tate are to use a Dattering

somewhat-in-awe tone of voice, and speak ItigbJy of tbe

source throughout this approach. This quickly prO<luces

positive feelings on the source's pan, as he has probably

been looking fOT this type of remgnidon aU oC his life.

The tnrerrogaror may bloW thln£J out of proportion

using items from the source', background and making

them seem notewonhy or important. Aa everyone is

eager to hear praise. the source wiJJ eventuaJJy reveal

3-17

FM 34-52

pertinent information to solicit more laudalory comments from the interrogator.

tabJisb a different type of rapport witbout losing aIJ

credibility.

. Effective targets for II successful pride and ego-up approach are usually the sociaUy accepted reasons tor flattery, s1Jch as appearance and good miliwy bearing. The

interrogator should closely walcb the SOUfCe'S demeanor

tor indications the approach is working. Some indiations to look for are-

Futility

In tbis approach, [he interrogator convinces the

th~t resistance to questioning .is futile. Wben

employing this technique, the interrogator must have

factual information.

facts are presented by the interrogator in a persuasive, logical manner. He should

be aware of and able to exploit the source's psycbologtcal and moral weamesses t II wen as weaknesses inberent in his society.

source

These

• Raising of the head.

• A look of pride in the eyes.

• Swelling of the chest,

The futility approach is effective wheb the interrogator can play on doubts that already ellist in the

source', mind, There are ditferent variations of the

futility approach. For example:

• Stiffening of the back.

Pride and E~Q-Down APproach. This approach is

based on attacking the source's sense-of personal wortb.

Any source who shows any real or ima~ed inferiority

or weakness about himself, loyalty to hiS organization,

or captured under embarrassing circumstances, can be

easily broken with thiS approach technique.

• Futility of tbe personal situation-wyou are not

finished here until you answer the questions."

• Futility in tbar "everyone talla sooner or later,"

• Futility of the battlefield situation_

The objective is for tbe Interrcgatcr to pounce on the

source's sense of pride by atlackin,e his loyalty, intelligence, abilities, leadership quaUtie.t, slovenly appearance, or any other perceived weakness. This will

usually goad the source into becoming detensive, and he

will try to convince the Interrogator he is 'MTong. In bis

attempt to redeem his pride, the source will usuaUy involuntarily provide pertinent information in anemptine

to vindicate himself

• Futility in the sense if tbe source does not mind

talking about histoJY, why should be mind lalking

about lIis missions, they are also history.

If the source's umt had run out of supplies (ammunition, fOOd. or fuel), it would be somewhat easy to convince him all of his Cora:.s are baving tbe same logistical

problems. A soldier who has been ambushed may have

doubts as to how he was atlacked so suddenly. The interrogator should be able to talk him into believing tbat

the intetro,ator's forces knew of the EPW's unit location, as ,...~u as manymore unitJ.

A source susceptible to tbis approach is also prone to

make excuses and give reasons why be did or ~id not do

a certain thing, often shlfting tbe blame to others. If the

interrogator uses a sarcastic, caustic tone of voice 9'ith

appropriate expressions of distaste or disgust, the

source wjIJ readily believe him. Possible targets for the

pride 3nd ego-down approach are the seurce's->

Theinrerrogator might describe the sourtZ', frigJueDing rec:oUections of seeing deatb on the battlefield as an

eveJYdayoccurrence tor his forc:es. Factual or seemingly

factual information must be presented in a persuasive,

logical manner, and in a matter-of-fact tone of voice.

• Loyalty.

• Soldierly qualities.

• Appearance.

The pride and ego-dawn approach is also a dead end

n that, if unsuccessful, it is difficult for the Interrogator

o recover and .move to another approach and rees-

(

I

is cooperating with the interTQgator. When employing ~;

this technique, the interrogator must not only have rae- .,

tual information but also be aware of and exploit the.:.

source's psychological, moral, and sociological wea1c- .:

nesses.

'.1

Another way 01 using the futiUty approach is 10 blow :i~:

things out of proportion. U the source's unit was I~ .'~~~

on. or had exhausted, aU food supplies. he can be easily ~.

/

-18

I

I

Making the situation appear hopeleM allows tbe

source to rationalize his actions, especially if that aeLioD "

• Technical competence.

• Leadership abilities,

-,'

I.

C

-

'r

1

a

n

JUN-22-2004

11:09

VUV

u~NcKHL

~UUN~CL

2~f~~i

FM 34-52

I·tt~·lh~.

~'f~~••

>OJ I·,

to believe aU or his forces bad run out of food. If the

is hinging on ccoperarlng, it may aid the Inter. . :·1:T.ogation effort jf he is told all the other source's have

d:·Wone.ra ted.

~;';:11ed

~;r, ~

...'

'.::~source

r.

r:

;'): ; The futiliry approach must be orchestrated with other

',~

t?approach techniques (for exampJe, love of comrades).

:,:' ..i4,'J~ source who may '¥ant to help &a~ his comrades'lives

",t .:::i"q~,JnaY be convinced the battlefield situation is hopejess

..i i.~.t,and they will die without his assistance,

'i~~"

'"

~: ;~~il';f.

The futility approach is used to paint a bleak picture

.:A:f!ft~ (~r tbe prisoner, but it is not effective in and of itself in

:' ,',,.r;\"~ gaining tbe source's cooperation.

~·;i~;:.l:

;i.· 'f<'

·It.,\

. . ".

:. ':',

.

We KnowAll

. approach may b

l eoyd In

. conJUJlClJOD

.

Thl!

e emp

•h

WJt

... the -tile and dossier- technique (discussed below) or by

J;:1i.~~' itself. U used alone, the interrogaror must first become

, "{:tf~·.,

thoroughly familiar 90ith avaiJable data concerning the

source. ,To begin the interrogation, the interrogator

:.r~. asks questions based OD this known data. Wben the

')}?'~i;; :soura: ~esitatesJ refuses to answer, or provides a.n incor. . . fl;,;i .reer ,or Incomplete reply, the interrogator provides the

: i~!~;::

..

. ~~: ,detailed answer.

"'~~'

When the source begins to give accurate and com; ~~~: plete Informadon, the interrogator inlerjects questions

~!,~: designed 10 gain the needed information. Questions to

, ~r}r \which answers are already knOWD are also asked to test

,:::;(.the source's truthfulness and to maintain the d~ption

, .-;. that the information is already known. By repealing tJW

,

procedure, the interrogator convinces the source that

resistance is useless as everything is already know;n.

:, ')t{ "

.

the

After gaining tbe source's cooperation,

interrogator still tests the extent ot cooperation by periodically using questions 10 which he has the aD5WClSj

this is vel)' necessary. If the interrogator does not challenge the source when he is )ying, the source will know

evel)'thing is not known. and he has been tricked. He

may then provide incorrect 8mwen to the intenogators

questions,

,.

~

"

f

r

There are some inherent problems with the use of the

OIwe know all' approach. The interrogator is required to

prepare everythlng in detail. whi~ is time consuming.

He must commit much ot the information to memory,

as working from notes may show the Untig of tbe information actually known.

File

and D088ler

The tile and dossier approach ia 1I5ed when the Iaterrogator prepares a dossier coDtai'ling aU available information obtained from documents Qlncernin& the source

or his 0FJanizatiOD.

Careful ;arrangement of the

material WIthin the

may give the illusion it contains

more data tban aettlally there. The file may be padded

with extra paper, if necessal)'. Index tabs with titles such

as education, employment, criminal record, military setvice, and others are particularly effective•

me

The interrogator tonfroolS the source with the dossiers at the beginning of the interrogation and explaina

intelligence haA provided a complete record of every significant bappening in the source's life; therefore, it

\'would be useless to resist. The interrogator may read a

few selected bits of known data to funber impress the

source.

If the technique is successful, the source: will be in:'

timidated by the size of the me, conclude everything is

known, and resign himself to complete cooperation.

The success of this technique is largely dependent OD

[he naivete of [be source, volume of data on the subject•

and sIeHl ot the interrogator in convincing the source.

Eatabllah Your Identity

This approach is especially adaptable to interrogation, The interrogator insists the source has been correclly identified as aft infamous individual wanted by

higher alJthoritia Oil serious charges, and be is not t!le

person he purports 10 be, In an effort to clear himself or

this allegation, the source makes a genuine and detailed

effort to establiSh or substantiau: his true identity. In so

doing, be may provide the Interrogater lJIIith information

and leads for further development,

The -establish your identity" approach was effective in

Coni and in OPERATIONS

Viet N8.Q1 witb the Viet

JUSTCAUSE and DESERTSTORM.

This approach can be used at tactical echelons, The

interrogator must be aware jf it is used in conjunction

witb the file and dossier appr08cl1, as it may exceed the

tactical interrogators preparation resources,

The interrogator shouJd ini~ially refuse to believe the

source and insist he is the criminal wanted by tbe ambiguous higher authorities. This wiJJ torce lbe source to

give even more detailed information about his unit in

order to convince the interrogator he is who he sa}S he

is. This approach works weU when combined with the

"turility" or "we know

approach.

an·

1

;1

)

j-

l.

3·19

-- _....

-~

......

=M 3...52

Repetition

This approach is used 10 induce cooperation fro~ a

ostile source. In one variation of this approach, the inerrogator listens carefuJIy 10 a sour~'s answer to a

uestion, and then repeats the question and answer

everal limes. He does this with each succeeding ques-

on until the source becomes So thoroughly. bored wilh

ie procedure he answers questions. fully a.nd candidly 10

Itisfy the interrogator and gam relief from the

ionotony of this method.

The repetition technique must be judiciously used. as

will generally be ineffective whe!1 employed against

troverted sources or those having great self-control,

i fact, it may provide an opportuni~ for a s~urce to

gain his composure and delay the mterrogauon, In

is approach. the use of more than one_ interrogator or

rape recorder has proven'effective.

.

Rapid Fire

This approach involves a psychological ploy based

on the principles that-

• Everyone likes to be heard when he speaks.

• It is contusing to be interrupted in mid-sentence

with an unrelated question.

.

Fhis approach may be used by one or simultaneously

two or more interrogators in questioning the same

iree. In employing this technique, the interrogator

s a series of questions in such a manner that the

rce does not have time to answer a question eomtely before the next on~ is asked.

'his contuses the source and he will tend to conlict himself. as he has nnte ume to formulate his

....ers, The interrogator then confronts the source

I the inconsistencies causing furt~er contradictions.

many instances, the source will begin to talk freely

an attempt to explain himself and deny the

rrogator's claims of inconsistencies. In this attempt,

source is likely to reveal more than be intends, thus

ting additional leads for further expJoit2tioli. This

'oach may be orchestrated with the pride Bnd egon or fear-up approaches.

I

Besides extensive preparation, tbis approach requires

experienced and competent interrogator. with comprehensive case knowledge and fluency in the source's

language.

an

Silent

This approach may be successful when used agaiD.'lt

the nervous or confident source. When employing this

technique, tile interrogator says nothing to the source,

but looks him squarely in the eye, preferably with a

slight smile OD bis face. It is Important not to look aMy

from the source but force him to break eye contact first.

The source may become nervous. begin to shift in bi!

chair, cross and recross his legs, and Jook away. He may

ask questions, but the interrogator should not answer

until be is ready to break tbe silence. The source may

blun out questions such as, ·Come on now, what do you

want with me?"

When the interrogator is ready 'to break silence. he

may do so with some nonchalant questioD& sucb as,

·You planned this operation (or a long time, didn't you?

Was it your idea?" The interrogator must be patient

when using this technique. It may appear the technique

is not succeeding, but usually will when given a

reasonable chance.

Change of Scene

The idea in using this approach is to gel the source

al"ay froID the atmosphere ot an interrogation room or

setting. If the interrogator confronts a source who is apprehensive or frightened because of the interrogation

environment, this technique may prove effective.

In some circumstances, the interrogator may be able

to invite the source to a different sellin, for coUee and

pleasaat conversation, During the conversation in tlUi

more relaxed environment, tbe interrogator steers tbe

conversation to the topic of Interest, Througb this

somewhat indirect method, he attempts to elicit tbe

desired information. The source may never realize be is

being Interrogated,

Another example in this approach is an interrogat~r

as a compound guard and engages the s?urce 10

conversation, thus eliciting the desired information.

poses

QUESTIONING PHASE

.e interrogation effon has two primary goals: To

n information and to report it Developing and

; good questioning techniques enable the inter-

rogator to obtain accurate and pertinent information by

tollO\lling a logical s~uence.